The types of avalanche to be aware of, the warnings that the weather can give, tips from Mountain Rescue on risk avoidance and what to do in the worst case scenario

Avalanches occur when the force of gravity on a body of snow becomes sufficient to trigger the snow to move, at speed, downhill. Scotland sees more snowfall than the rest of the UK and, as such, the most avalanches (237 in 2015) but they’ve also been known to occur in England and Wales too. Any hillwalker venturing out into the snowy hills needs to be aware that avalanches are possible, and to have an understanding of the circumstances in which there is the greatest risk. This is a complex topic and we are only able to give some basic information here. We’d thoroughly recommend you take the time to read up around avalanches (see references at the end of the article) and, ideally, attend a training course.

Types of avalanche

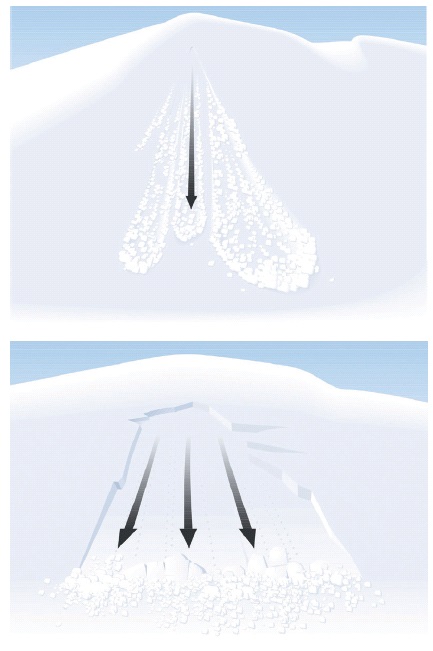

The two main categories of avalanche are powder and slab are:

Powder avalanches (top image on right) occur during periods of heavy snow fall on still days or days with only light wind. As such, they are relatively unusual in the UK, but the greatest risk of them occurring is during snowfall or soon afterwards, before the snow has had the opportunity to go through a cycle of thawing and freezing.

Slab avalanches (bottom image on right) are the most common in this country. They occur when an area of snow breaks off from the snowpack. Snow builds up in layers, and there may be weakness in the lower layers which can cause upper layers to become detached. This is often triggered by human activity but could also be caused by climatic changes or build-up of snow. Slab avalanches occur most frequently on slopes of between 30 and 45 degrees, and are more common on convex slopes than concave ones. Risk is usually lower on ridges, and there is usually less danger on some slope aspects (compass direction) than on others. Information on this is available daily in winter from the Scottish Avalanche Information Service.

Weather warnings

Changes of weather can disrupt the snowpack, leading to potential avalanche conditions.

Intense snowfall will cause instability on the snowpack. Watch out particularly for more than 30cm continuous build-up, or more than 2cm in the course of an hour.

Heavy rain can also destabilise the snowpack, causing wet snow avalanches.

Sudden temperature rises can cause thawing, making the snow denser and wetter.

Strong winds can deposit snow on lee (downwind) slopes.

Cornices and raised footprints are often signs that strong winds have occurred recently.

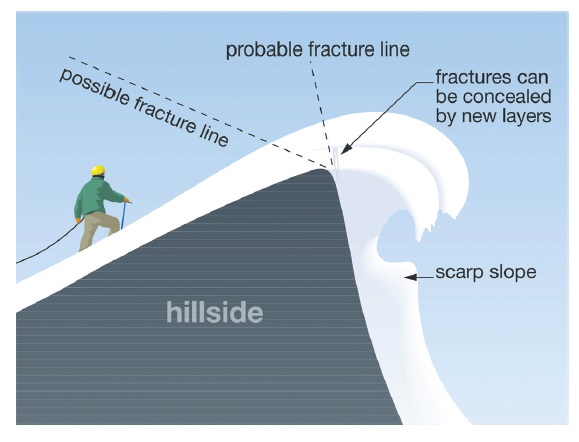

Cornices

Cornices are overhanging masses of snow at the edges of mountain ridges and gullies, formed by a horizontal build-up of snow. Many avalanches are triggered by the collapse of a cornice so be aware when walking above, or underneath them – particularly during or immediately after snowstorms or heavy winds or during sudden temperature rises. The illustration above from the Mountain Training guide to Winter Skills illustrates how far back the break-off point of a cornice could be.

A mountain rescue perspective

“South of the border it can be easy to underestimate the risks of avalanche,” says Mike Margeson, Operations Lead of Mountain Rescue England and Wales. “While we do not have anything like the same severity of hazard as Scotland, our mountains in winter conditions can still present serious avalanche risk and people need to be aware. It often shocks people to know that 90% of avalanche victims trigger their own avalanche.” Mike’s top tips for avoiding potential avalanche situations are:

No.1

Seek local sources of information on the present conditions before departing. Be particularly aware of any notorious terrain traps and ‘black spots’, such as the central gully on Great End.

No.2

Don’t just read the day’s forecast but the day before as well. Consider the wind direction and any temperature changes. It does not have to have been snowing for the last few days.

No.3

If it has been windy, blown snow can accumulate on slopes and become dangerous.

No.4

Unstable wind slab accumulates on lee slopes. Ensure that your planned route takes account of the hazard.

No.5

If you intend to climb an easy gully or slope, consider what condition the cornices and upper slope above your route might be in.

No.6

Snow that feels ‘squeaky’; snow that creaks or cracks; and seeing evidence of avalanche debris are all clear signs of dangerous conditions. Change your route or leave it to another day.

No.7

Just because somebody else has crossed a slope does not mean it is safe for you to do so.

No.8

Avoid convexities of slope (upward bulges) where snow layers are under tension. Be aware of people above you on a slope or climb – whatever they loosen may be heading for you.

No.9

Remember that the bravest decision can often be to turn back or alter your route and save that winter route for a safer day.

Avalanche awareness

Click here for a vitally important three-stage breakdown on safety approaches from National Outdoor Training Centre Glenmore Lodge

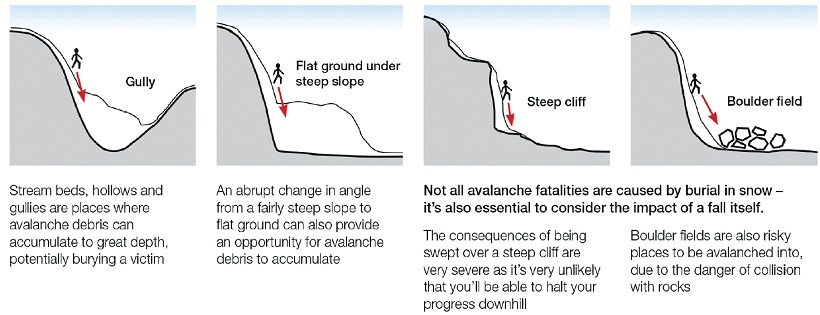

Terrain traps

Terrain traps are places where avalanched snow could accumulate, with the risk of a deep burial for any victims caught in an avalanche, or where the consequences of even a small slide could be very dangerous. “In times of high avalanche risk avoid gullies, abrupt slope transitions and corrie basins – and remember: it might not be you that triggers the avalanche, you could just be in the firing line,” warns Heather Morning of Mountaineering Scotland. “Stay high – always choose ridge lines and broad shoulders.”

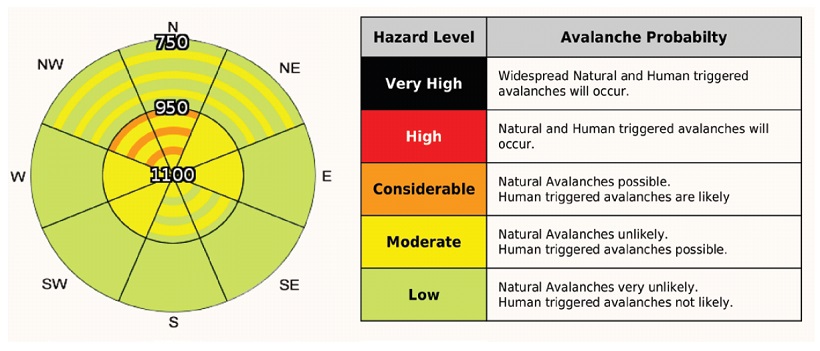

The Scottish Avalanche Information Service

Through the winter, SAIS publishes daily reports of avalanche, snow and mountain conditions in five of the most popular mountaineering areas of Scotland. The forecasters bring together their reports using hazard evaluation techniques in the field combined with Met Office weather forecasts. As well as written descriptions, the reports feature an ‘avalanche rose’ which is a visual representation of the risk on varying slope aspects (on most days, some aspects will have significantly lower risk than others). In this example, there is mostly low risk below 950m, with localised areas of moderate risk between north-western and north-eastern aspects. Above 950m, the risk is generally moderate, with localised areas of low risk between southern and south-eastern aspects, and localised areas of considerable risk between north-western and northern aspects.

Danger signs

Using your ears and your eyes is vital. Key danger signs to look out for in potential avalanche terrain are:

- ‘Whoomphing’ sounds, which indicate a weak layer collapsing below

- Cracks shooting away from beneath your feet

- The snowpack cracking or breaking into blocks

- Evidence of recent avalanches.

Human factors

Two seasons ago, Alan Halewood wrote a detailed article for TGO about the ‘heuristic traps’ that people fall into which mean that they don’t take the precautions that they should when heading into terrain where there’s an avalanche risk. Here are the six key heuristic traps he outlined:

Familiarity

Assuming that we will be safe this time because we have been in the past.

Consistency

Unwillingness to appear indecisive, unsure or inconsistent (even to ourselves).

Acceptance

Allowing our desire for acceptance to override our own decision-making process.

The expert halo

Deferring automatically to the ‘expert’ within the party.

Social proofing

Belief that those similar to you have taken the best course of action and following in their footsteps.

Scarcity

Allowing the desire for a day out to override other factors in the decision-making process.

When avalanches happen

Giles Trussell of Glenmore Lodge offers some tips on what to do if you see someone get avalanched…

No.1

Note and mark the place last seen

No.2

Check that the area is safe from further avalanches

No.3

Start searching for any signs on the surface down from the point last seen

No.4

Probe in a structured manner with whatever you have available – axe or ski pole or an avalanche probe if you’re carrying one

No.5

Leave any objects found in place – they can be recovered later

No.6

If you find the victim, start digging

No.7

If you believe they’ve been buried less than a metre down, dig straight downwards

No.8

If they’ve been buried by more than a metre, start downhill a distance 1.5 x the burial depth

No.9

Call 999 as soon as possible, ensuring you have prefixed grid reference ready

The Scottish Avalanche Information Service keeps records of any British avalanches. If you witness or are involved in any incidents, report them via their website.

Avalanche survival

“The first thing is shout – shout, shout, shout. Because if you get buried, the only chance you’ve got of getting out is other people. Make sure that your other companions are alert to your circumstances.”

That advice comes from Mark Diggins, who heads up the SAIS. From talking to people who have been involved in incidents, he knows that it’s often impossible for avalanche victims to do much more than that. If you are unlucky enough to get caught in an avalanche situation, try also to shed your pack and other gear, and roll or swim towards the surface of the snow. Do your best to make some space in front of you to breathe, by keeping a hand in front of your face to prevent snow blocking your nose and mouth.

Further information

Books

Winter Skills: Essential Walking and Climbing Techniques by Andy Cunningham and Alan Fyffe, published by Mountain Training UK

A Chance in a Million: Scottish Avalanches by Bob Barton and Blyth Wright, published by the SMC

Staying Alive in Avalanche Terrain by Bruce Tremper, published by Bâton Wicks

Online

Scottish Avalanche Information Service forecasts: www.sais.gov.uk

SAIS Be Avalanche Aware site: www.beaware.sais.gov.uk

Glenmore Lodge avalanche safety pages: www.glenmorelodge.org.uk/outdoorresources/avalanche-information

Swiss avalanche education site: www.whiterisk.ch/en

European site www.avalanches.org

Lead image by Shutterstock