With the number of mountain rescue incidents caused by people relying on Google Maps rising, we explain why using it for hiking is a bad idea.

Those new to outdoor activities might wonder if they can utilise Google Maps for hiking instead of purchasing a GPS watch. It’s an excellent way to go about towns and cities, so why not hills and mountains?

Here, we examine how Google Maps works and why it is unsuitable for traversing alpine terrain – and can even lead to accidents that require rescue.

Words: Francesca Donovan | Main image: Jessie Leong

Can you use Google Maps for hiking?

In short, no, Google Maps is not appropriate as a tool for navigating when hiking.

Google Maps is great for navigating in urban areas, including on foot. It combines satellite imagery, aerial photography, street maps, 360° panoramas, and real-time traffic updates, as well as image recognition, machine learning and geospatial data analysis – not to mention integrations with Google Earth and Google Street View.

But does it work for the purposes of hiking in the hills, the mountains, or the wider countryside? No, because it simply isn’t designed with outdoor activities in mind. The maps used by Google Maps simply don’t contain enough information about trails, terrain or topography to properly plan hiking routes, let alone use them as a navigational tool when you’re out there.

Google Maps does contain some information which could be relevant to hikers, but only at a very basic level. This can be useful to get a very quick, at-a-glance idea of what an area is like, but if you’re planning to actually walk there, you need a lot more functionality and detail.

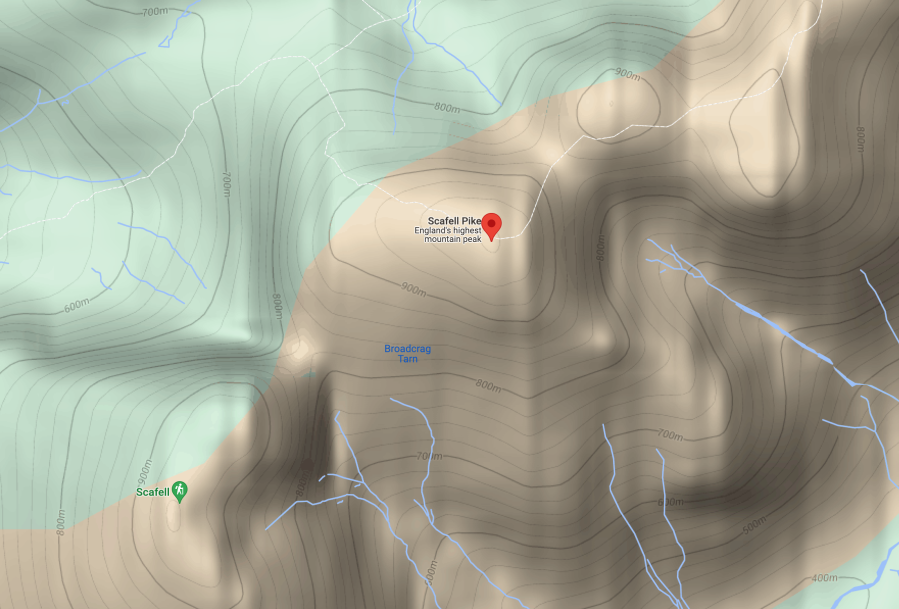

Let’s take a look at a specific example. Here is how Scafell Pike, England’s highest mountain, and its neighbour Scafell, appear on the ‘Terrain’ layer of Google Maps.

Some information is presented, such as the most popular trails, but many paths are missing. There are 20 metre contour lines, which give a very broad idea of the shape of the terrain, but there is very little detail to indicate where the terrain is hazardously steep, craggy or impassable. There is simply not enough information to use this map safely as a planning or navigation tool.

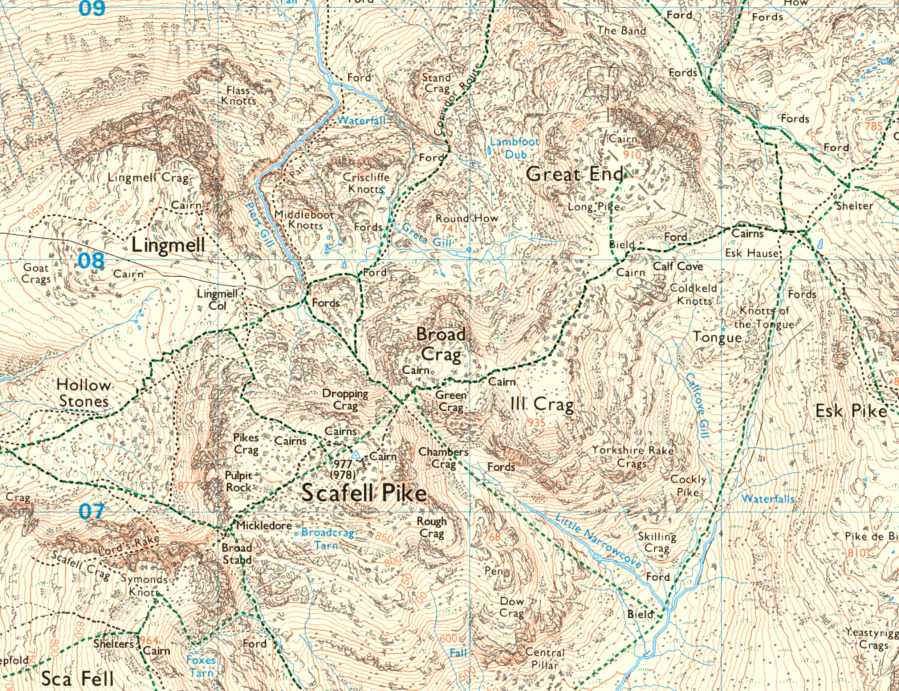

This is what the same section of terrain looks on a full-detail topographic map suitable or hillwalking and hiking, in this case the 1:25,000 Explorer layer of Ordnance Survey.

There are 10-metre contour lines, giving a much better sense of the steepness of the landscape, plus additional topographic detail such as crags and rocky terrain. The information on rights of way and paths is much more extensive, water features are shown in much more detail, plus other geographical details like shelters, cairns, and walls are visible.

All this information is vital to plan properly and help you navigate safely, particularly in bad weather or poor visibility, when you may be relying on small details of the landscape to help you locate yourself.

Ultimately, at the root of all hiking navigation – especially in the hills and mountains – is the ability to read and interpret a topographic map, like the one above. This is a skill which applies with both paper maps and digital maps. You’ll find it very hard to hike without it, even in lower-level countryside, but it becomes absolutely essential in upland or mountainous terrain, where the potential hazards increase.

If you’re not sure how to read a topographical map, or do other navigation basics, check out this beginner-friendly article to learn more…

Beginner’s guide: How to use a map and take a compass bearing

As well as interpreting a map, it’s also essential to properly research the route you are thinking of hiking. Take Helvellyn, for example; the popular round of Striding and Swirral edges involves grade 1 scrambling, with steep terrain and potentially fatal drops, making it only suitable for experienced walkers, but this information is poorly presented on Google Maps – you have to scroll through user reviews before you see any reference to it.

Hiking apps: how to use them safely

Proper digital navigation tools, with the right information, can be an important part of navigating safely.

Google Maps is not designed for outdoor use, but a wide range of apps are. Any specialist hiking app will contain much better maps for hiking use than Google Maps. Most maps provide ‘free’ layers, usually based on open source Outdoor Street Map data. While this information can be useful, and is usually fine for navigating in lower-level areas, it can sometimes be presented in misleading ways by some hiking apps, and it also contains less information than a high-quality topographic map such as those produced by Ordnance Survey.

Apps like Komoot offer some fantastic route discovery and community features, but they do not offer the best quality topographic mapping, making them better for planning and inspiration than technical, high-level navigation.

Check out our review of the best hiking apps to find out more.

For high-level use in the mountains, we would always strongly recommend buying the best possible topographic mapping available. This usually involves paying a fee of some description, but it is well worth it. In the UK, the best quality mapping is either Ordnance Survey or Harvey Maps. Ordnance Survey maps are offered through OS Maps, and Outdooractive offers both Ordnance Survey and Harvey, as well as the best available topographic mapping in other countries.

All specialist hiking apps will also allow you to download maps for use offline, as you are often unlikely to have data coverage when out in the mountains and more remote areas of the countryside. Specialist hiking apps will also contain a lot more functionality for plotting and planning routes than Google Maps offers.

James Forrest using a hiking app in the Lake District. Credit: Jessie Leong

Ultimately, all digital navigation apps are simply tools, and when it comes to navigation, you need the widest possible range of tools at your disposal to give yourself as many back ups and fallback options as possible.

The ‘traditional’ method of navigating with a paper map and compass is still essential to learn, as it provides the foundation for your navigation skills and gives you something to fall back on in case other technology fails you.

On the other hand, paper maps can blow away or get damaged, and compasses can fail, so having digital maps available on your phone or a mapping device could be a lifesaving backup. The more options you have, and the more knowledge you have of using them, the safer you will be.

A walker checking their OS Map at the summit of Cadair Idris. Credit: Jessie Leong