‘Rewilding’ and environmental restoration is increasingly becoming big business. Should we celebrating? Not quite, argues David Lintern.

Main image: Arran’s community campaign against an open-cage aquaculture proposal. Photo: James Appleton

In his poem A Man in Assynt, Norman McCaig asks, “Who possesses this landscape? The man who bought it or I who am possessed by it?”

Last year, just before COP26, there was a new spin on McCaig’s eternal question. ‘Real Wild Estates’ was announced as an innovative business solution to enable rewilding, variously described by millionaire environmentalist Ben Goldsmith as ‘an estate agency’ for investors in nature and by ecologist Alastair MacIntosh as “a rich man’s solution for a rich man’s world”. Newly employed by the company, the author Ben Macdonald said the aim was “…to make nature pay, by delivering sustainable business returns.”

The phrase ‘make nature pay’ sounds like something a James Bond baddie might say, but to be fair Macdonald is far from the only villain of the peace. There’s a growing number of corporations buying up land to offset carbon emissions generated in their main business.

‘Green lairds’

Way back in the early months of 2021 in the Cairngorms, an insurance company spent £7.5 million on land for carbon offsetting, while beer makers Brewdog spent a similar amount, promising the planting of a ‘lost forest’. Online retailer Amazon later purchased the entire output of a windfarm on Kintyre to power their offices and warehouses. In the first days of 2022, another insurance company announced the purchase of open moorland in Aberdeenshire for tree planting and peatland restoration.

These new ‘Green Lairds’ aren’t just confined to Scotland. In 2021, several Welsh farms were snapped up for afforestation by London based investment company, The Foresight Group. Even musician Ed Sheeran is getting in on the act – it was recently announced he was “trying to buy as much land as possible and plant as many trees as possible”, to offset the high carbon impact of global touring.

Kinrara Estate, now owned by Brewdog. Photo: David Lintern

None of this is happening in isolation. Conservationists have long talked up the benefits of ‘ecosystem services’ – things like flood mitigation, water cleanliness and the carbon storing ability offered by peatland and woodland – and wider recognition of the value of ‘natural capital’. Useful jargon for talking to politicians, maybe, but it was just a matter of time before big business saw an opportunity. Recently, a new ‘asset class’ was set up on the New York Stock Exchange. These Natural Asset Companies (NAC) are backed by big players in private healthcare and international development.

Commodity

The stage is now set for the buying and selling of nature as a commodity. After COP26 green-lighted this emerging market, trade in carbon credits is apparently ‘bullish’. How will the profits be spent? Will the market decide how and where to repair our broken environment?

Some make the case that fixing the nature and climate emergency will not be cheap, and the clock is ticking. “Those peatlands aren’t going to restore themselves,” goes the argument. Perhaps we don’t have time to be squeamish?

One of the few more positive outcomes of COP26 has been in raising awareness. The problem with buying land to offset business as usual is, of course, that it allows business to continue as usual. After COP26, more of us know that we can’t offset the future by carrying on as before… with just a bit of compensation on the side. More of us are wise to the fact that tree planting on its own won’t be enough to stop global heating racing past a 1.5 degree rise. We’re even getting used to the idea that planting just one type of (fast-growing, non-native) tree won’t prevent wholesale species extinction.

It’s worth saying that asset managers aren’t just investing in greenwashing, either – this is about more than just marketing. Some are looking ahead to carbon taxes. Others plan to access public funding in the form of government subsidies, to pay for restoration and planting schemes. These businesses aren’t paying to make the places we love to backpack and hike in more nature-friendly, or better at storing carbon. We are.

Inequalities

We’re also paying in another way, because this new spin on land speculation does nothing to address old inequalities in the countryside. For Scotland in particular, fewer people own more land than anywhere else in Europe. In a superheated property market, large corporations have the muscle to outbid community efforts, despite those efforts being more sustainable, longer-term.

The Langholm/Tarras valley nature reserve in Southern Scotland, recently bought by the local community. Photo: David Lintern

From community-owned Knoydart and the Isle of Eigg, to the 200 or more community woodland groups across Scotland, the lessons are clear: local people have an intimate understanding of their home turf, and that means environmental changes

can be synchronised with the social and economic. Done in this way, nature is more likely to get the support that it needs from us all. Everyone benefits, whether they are hillwalkers or not.

To those who argue that local, people-powered solutions lack the scale or ambition of larger estates, we need look no further than the recent Langholm community buyout or the grass roots support for the marine No Take Zone on Arran.

And what about the vulnerabilities? What happens when an ‘asset’ changes hands to a landlord who prefers pheasants to peatlands, or when markets ‘innovate’ again and begin to hedge against hedgerows? Local autonomy is safer than a market- driven monoculture because there are fewer eggs in any one basket. Just like nature itself, strength lies in diversity.

People power

People power is fairer, too. A graph provided by Real Wild Estates showed that more profit was expected through real estate and ecotourism than from storing carbon and improving habitats. Low-paid work and land banking sounds suspiciously like what people in the Scottish Highlands have endured since the Clearances. “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss,” read one response on social media.

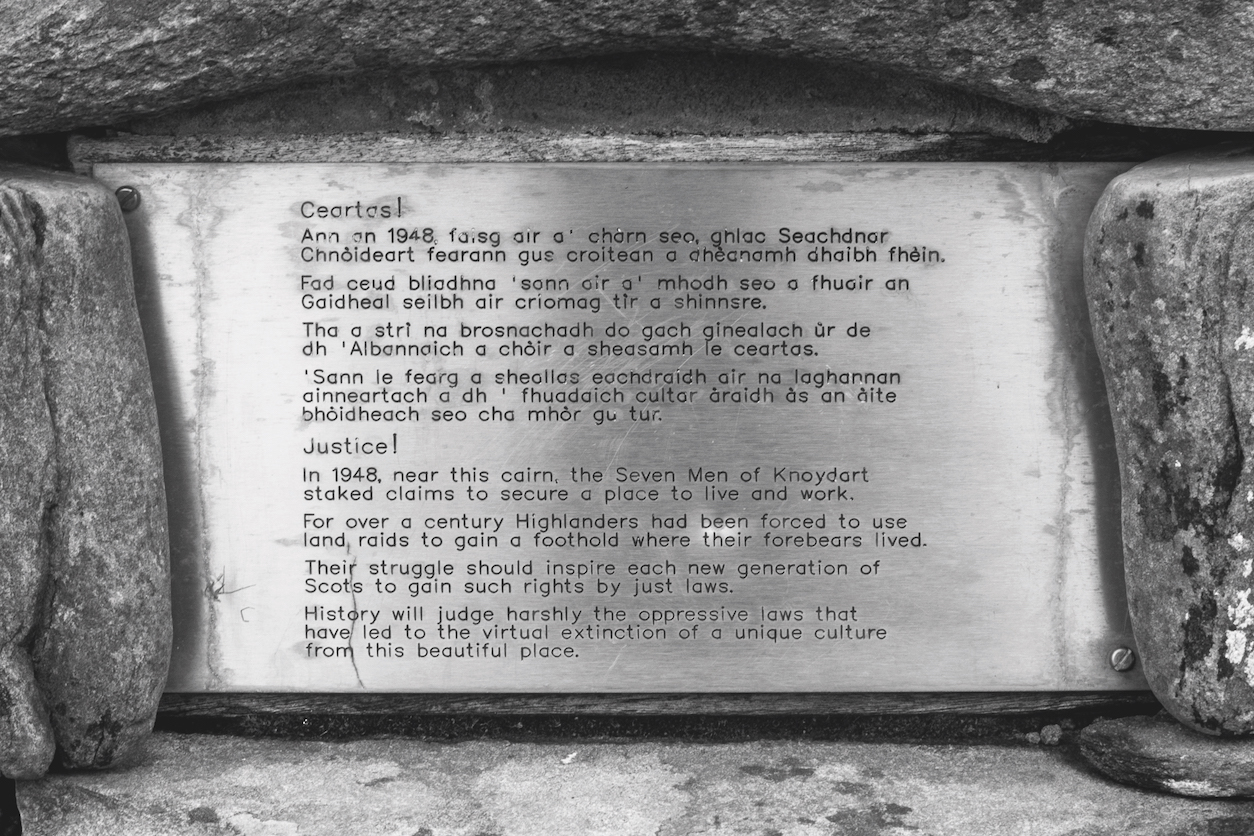

The ‘Seven Men of Knoydart’ plaque on Knoydart. Photo: David Lintern

Waiting in the wings, climate sceptics and fossil fuel financiers are primed to take advantage of this disconnect and poison the growing well of public goodwill for restoring nature, by lobbying against net zero regulations. There’s even a nascent referendum campaign.

That’s why it’s key that change is from the ground up. Those at the top have the power and money to support and assist community efforts, but not through remote brokering companies making vague promises on international stock markets.

The ‘eco-entrepreneurs’ could start by listening. Nature has paid enough already.