Artist and writer Bryony Ella explores the ‘uncanny’ of our nature crisis through her art practice and wild drawing workshops.

The scent of cow parsley, “towering green and white” above her, still draws Bryony Ella back to childhood in Bradford. Here, her mother worked as a community artist and many of Bryony’s earliest memories feature her “small hands full of crayons and paint brushes.” She carried a small rucksack filled with pencils and colouring books wherever she went.

Main image: Bryony’s work is curated in the setting sun | Credit: Ewelina Ruminska

At eight, her family relocated to Kent. Bryony’s backpack of crayons and biophilia came, too. She “always felt safe” exploring the forest and orchards, forming a motley crew with other village kids. They ran through the understory pretending to be wolves, owls, cuckoos as they called to each other. Now 40 and living in New York, where she is working with environmental historians on a project looking at urban heat islands through a climate justice lens in order to “cultivate of new value systems and structures that work far more in harmony with the natural world”, Bryony is grateful for her childhood in nature.

Here, we discuss her ever-developing art practice, drawing as a route to rethinking our concept of belonging in nature, as well as the Right to Roam movement and Wild Service.

Posing with flowers since 1989. Credit: Sharon Hogan

TGO: Can you describe your formative experiences in nature throughout your childhood?

Bryony Ella: Although I was born in Yorkshire, my early memories of the great outdoors are largely contained to my immediate neighborhood rather than the vast hills and dales of the county; in Bradford we lived on (what felt to me) a large plot of land in one of the flats of an old Victorian mansion atop a small hill. I can still call to mind the vast spread and scent of cow parsley that wrapped around the house and vividly remember the joy of running through it, small amongst towering greens and whites. Today, cow parsley still draws me into my child body every time I smell it, always evoking memories of curiosity, wonder and freedom.

At eight years old my family relocated to Kent. I write in Wild Service of my memories of exploring the forests and orchards at the edge of our village. I was lucky to live close to families with children of a similar age and, unsupervised, we would go into the forest as a small motley crew to play amongst the bracken and beech trees. I always felt safe there, climbing trees and running wild as we played our own version of hide and seek, pretending to be different animals as we called to each other as wolf or owl or cuckoo through the understory. I am so grateful to have had a childhood in which I was able to play, explore and feel safe in nature.

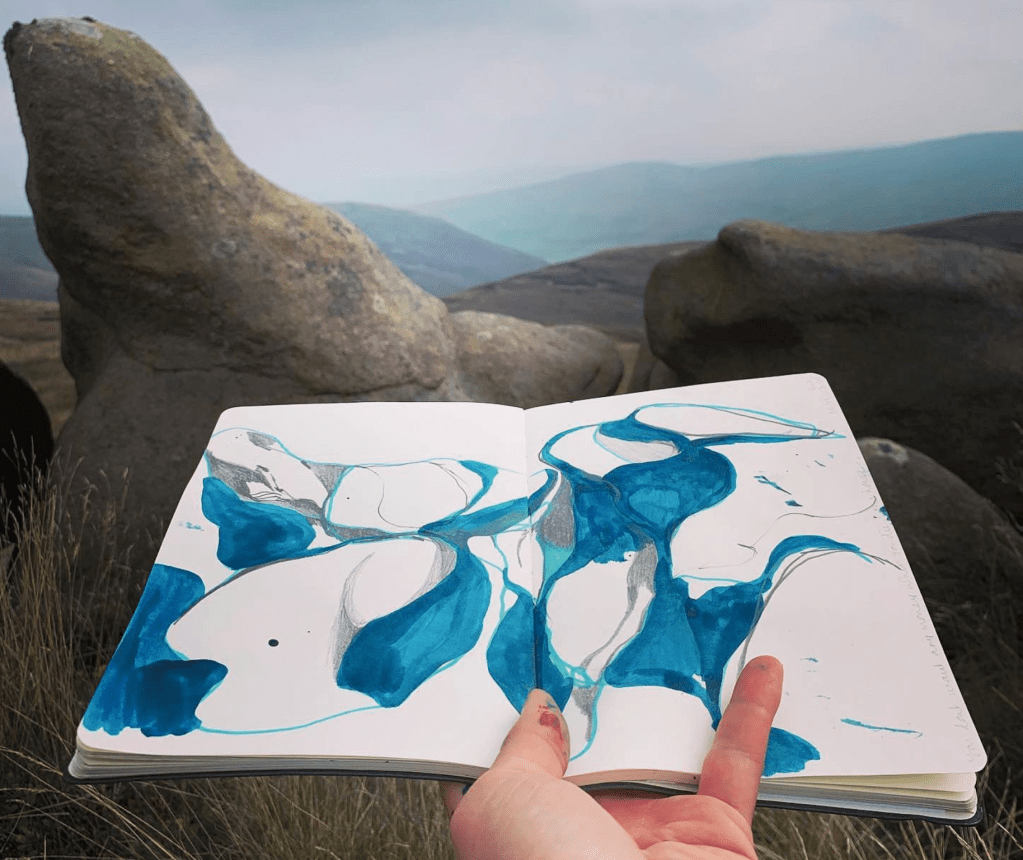

Wild drawing on Kinder. Credit: Bryony Ella

TGO: When did you first begin to draw and what continued to draw you into this form of creative expression?

Bryony Ella: My mother had been working as a community artist in Bradford when she had me, so many of my earliest memories are of being creative; of my small hands being full of crayons, pens and paint brushes, and of carrying with me a small rucksack filled with pencils and colouring books wherever I went.

Drawing has continued to accompany me everywhere I go, though my relationship to it has gone through several phases since then. In 2003 I went to university where I specialised in painting, and drawing then became more of a tool to map compositions and collect visual references, rather than a form of self-expression in and of itself. However, art school also introduced me to life drawing, and over the years I have returned to this study of the human form whenever I have found the time. I enjoy how life drawing challenges my ability to quickly capture the essence of the model in just a few lines, or pushes me to commit to longer observations of the folds, contours, shadows and gesture of the human form.

Creating the ink drawing series ‘Shadow Dancing’ in Kent. Credit: Bryony Ella

Today, my relationship to drawing is more sensory-led. Inspired by the natural world, I have developed a way of drawing that I call ‘wild drawing’, which is all about tapping into an embodied sense of self as nature. Over the past four years I have been exploring different ways of drawing with breath, sound, touch, smell and movement in, of and with nature, and now lead guided wild drawing walks. Sometimes these are in collaboration with scientists, who bring fascinating, detailed insights on human-nature relationships.

What I love about wild drawing is that it challenges the notion that so many of us have held since childhood that we can’t draw, because it is messy, playful and encourages an ecocentric perspective. The ego is decentralised; there is no pressure to create picture-perfect representations and I always encourage participants to keep their drawings private unless they really want to share them with the group.

A wild drawing ‘walkshop’ with Peaks of Colour. Credit: Ai Narapol

TGO: Why is it important to you personally to recreate these moments of childlike wonder through embodied nature connectedness and ecology?

Bryony Ella: Akiko Busch writes beautifully on how children are able to look at the world with a sense of awe in her book How to Disappear: Notes on invisibility in a time of transparency. In it she asks if we need to feel small in order to experience awe and wonder, or whether awe and wonder itself makes us feel small. This question has stayed with me over the years as I consider why I am so drawn to letting my inner child lead how I engage with the landscapes around me and their inhabitants.

There is something so brilliant in the way in which children can intuitively encounter the natural world as kin, and I often think that if only we adults could hold onto that sense of wonder then maybe, just maybe, we would make different choices about the boundaries, borders and structures we have designed into our lives to shape and filter the ways in which we relate to nature. I know that the more time I spend creating art from a place of childlike wonder, my respect for all that nature is and gives only grows.

Dancer Ming interpreting Bryony’s work on metamorphosis. Credit: Ewelina Ruminska

TGO: Your art practice has consistently engaged with the natural world – from butterflies to flora growing through brick walls – both on canvas and within interdisciplinary art spheres. Why is nature the subject for you?

Bryony Ella: I find it hard to explain why nature is the subject I consistently return to, simply because I cannot imagine any other focus. It never fails to surprise, delight or humble with its infinite hues, forms, textures, scales, patterns, sounds… Why wouldn’t I pour my energy into celebrating this endless source of inspiration?! This is heightened all the more because of the nature crisis we are in the midst of; I profoundly feel the urgency to challenge dominant ways of seeing nature as something ‘less than’ to be tamed, extracted and othered. I guess I feel equally protective of and nourished by nature, and my creative practice helps me to engage with both of these felt-senses simultaneously.

In the studio. Credit: Bryony Ella

TGO: Your current research project is looking at urban heat islands – how has this impacted your support of and belief in the concept of Wild Service?

Bryony Ella: The reason why I am currently based in New York is because I am working with a team of environmental historians who are researching everyday, lived experiences of heat in three cities: New York, London and Paris. As the research artist on this ‘Melting Metropolis’ team, I am focusing in on embodied and emotional experiences of summer – the pleasures, pressures and behaviours of heat in the city.

In the book Wild Service, the authors speak to the fundamental right that everyone should have to access nature locally, and to be able to care for and form their own relationships with nature in ways that nurture our sense of kinship, custodianship and reciprocity. Where this intersects with Melting Metropolis is the fact that so many of those more greatly impacted by urban heat islands do not have equal access to the qualities of nature that would make living in hot cities more bearable, such as trees, parks, lakes and rivers, and they often live in close proximity to the things that exacerbate and trap heat, such as air pollution and tall, tightly packed-in buildings.

In America, extreme heat is the greatest weather-related cause of death, and those more likely to live in urban heat islands are communities of colour and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. Through a climate justice lens, Melting Metropolis’ research is helping to illuminate the myriad ways in which the historical design of cities obstructs fundamental human rights such as those discussed in Wild Service, amongst others.

From my perspective, I see both as a stepping back to understand how, where, when and why we have distorted our understandings of what we need to live healthy and happy lives, and from those vantage points, creating of space for collective, grassroots re-imaginings of the fundamental stories that we tell ourselves about what it means to be human. Informed by the past while looking to the future, the intention is to support the cultivation of new value systems and structures that work far more in harmony with the natural world. For my part in the project, I am exploring how the arts can amplify underrepresented voices within policy and in the public realm, in ways that resonate with those who are not yet facing the brunt of the climate crisis.

Painting in Tobago. Credit: Bryony Ella

TGO: You write beautifully in Wild Service about how wild drawing helped you rediscover belonging while in the rainforests of Trinidad and Tobago. What do you hope participants of your wild drawing workshops will gain?

Bryony Ella: The exercises I share are simple and designed to be either done on-the-fly, like field notes jotted down while walking, or extended into longer meditative exercises if participants have the time. Primarily, I hope that the experience is relaxing and that participants find that drawing is an accessible, low-cost and playful practice that is readily available to them no matter whether they have an art background or not. Beyond that, it is my hope they leave with a heightened awareness of how they are in contact with the environment and that this helps to strengthen and expand their sense of being in community.

I am fascinated by the concept of humans as humus; as organic, temporarily animated beings destined to return to the land; I explain how and why this interest emerged for me in Wild Service. Humus is the Latin root word for human, meaning soil or ground, and I came across this word while exploring the concept of embodied ecologies through the Society for Cultural Anthropology. For me, it has become a medium through which to gently tease open different ways of understanding our own bodies as humus – dynamic, ever-changing, porous – and I hope that participants also find wild drawing a gentle way of pushing at the concept of ourselves as separate entities.

The practice reminds me of the impossibility of not belonging to and in nature, and I hope that likewise it helps participants soften some of the more rigid human-defined boundaries that we’ve internalised to keep nature at arms length.

At a Peaks of Colour gathering in the Peak District. Credit: Ai Narapol

TGO: You collaborate with many organisations working towards dismantling the systemic racism which still puts barriers between the global majority and safe, comfortable access to the outdoors. Can you describe the feelings you experience when you adventure with the likes of Peaks of Colour and All the Elements?

Bryony Ella: Truthfully, I find this question difficult to answer as I find I am getting tangled up trying to explain the ‘why’ behind my feelings and realising that to do this any justice would require more time. I hope it is sufficient to simply share that when I am exploring the British landscape with groups of people of global majority heritage, my emotions are a kaleidoscope of joy, pride, solidarity, grief, compassion, inspiration, belonging, safety, care, serenity, anger, sadness, hope, gratitude, relief, and love.

Bryony’s ‘Follow the Lichen’ mural on the corner of Girdlestone Estate, Archway. Credit: Bryony Ella

TGO: Finally, how do you feel when you explore the outdoors today among the treeless mountaintops ridden of biodiversity to the sewage-ridden streams and rivers? Are able still able to find joy in these little moments of magic or does the burden of ecological activism weigh heavy? If the former, I wonder whether the act of noticing nature through your work helps?

Bryony Ella: Honestly? I struggle. However, art-making has been invaluable in helping to find metaphors, myths and new ways of moving that help me to process the grief and despondency I feel in those moments. I don’t think I could work in this field if I did not have a creative outlet; I would stay suspended in these states of being.

Witnessing the loss of landscapes and species I loved, and knowing that I will never walk through the landscapes or encounter the species that my ancestors loved, hits me daily. Likewise, I often find myself resenting how access to land is tightly controlled and restricted, limiting communal spaces to cordoned off patches of grass, to narrow, pre-defined pathways, to plastic imitations of nature, to waters polluted by sewage. These shrinking spaces cultivate a different kind of wild to that which we should be nurturing; it stirs a wild that rages and ricochets, rather than a wild that is instinctual, roams freely and is intimately responsive to the cycles, patterns and rhythms of the natural world.

I have had many conversations with colleagues about the fine line we dance between hope and despair. Working with creatives and academics who are seeking new ways to either communicate human-nature interconnectedness or illuminate the systems that perpetuate the human-nature crisis gives me hope. The evolution of my art practice to focus in on embodied expressions of this research has been a healing journey, and collaborations with dancers, musicians, poets and writers has helped me to find alternative ways of processing my emotional responses so that they do not stay pent up in the body but can be grounded and released constructively. But the nature crisis is deeply uncanny, and to continue this work I have had to develop my own daily practice of allowing my emotions to surface and be expressed without allowing them to coat all that I see and do. Wild drawing is an immediately accessible way to process this, and paintings and installations are my more long-form ways of inviting others to wonder with me at the marvels of this world that we still have a chance to save.

You can follow the adventures of Bryony Ella through her ‘Embodied Ecology‘ Substack or at www.studiobryonyella.com.