For Alex Roddie, hillwalking and the natural world are closely linked – but it seems not everyone feels that way.

Header image: a wild camp in the Pyrenees on an evening full of birdsong. Photo: Alex Roddie

A few weeks ago, I opened my inbox to find a message that astonished me. “I enjoy reading your mountain writing. But what’s with your recent digressions into nature, wildlife etc? I don’t follow you for that, I follow you for the outdoors. Please return to writing about outdoor subjects.”

After I managed to get over my initial shock, I found myself pondering what this might say about the state of outdoors writing – and how we treat our wild places.

Like many people, since the pandemic began I’ve been spending a lot of time in my local area, walking the same few local walks. In an average year, I’d spend at least two months out there on the trail in wild, remote places. My response to 2020 was to develop my skills as a wildlife photographer and begin a detailed study of the wildlife in my local nature reserve – which I soon found was a place of true riches. My writing and photography have broadened to reflect this change, and on my Instagram feed you’ll find pictures of barn owls next to images of snowy wild camps. In my mind, there’s no fundamental difference. The reason why I go to the mountains is to enjoy time in wild nature. Rural Lincolnshire may lack the outdoors cred, but it can scratch the same itch – to an extent, at least.

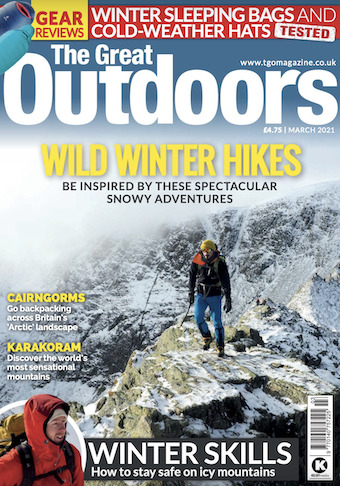

What does ‘the outdoors’ mean, anyway? One of the reasons why The Great Outdoors has captured my attention, as both reader and writer, for longer than any other walking magazine is the fact that contributors are motivated at some level by a deep love and respect for nature – and this shows. Even features about adrenaline-fuelled mountain challenges are built on this foundation. But what about the outdoor world in general? Have we forgotten that there’s a direct connection between bagging that Munro and the golden plover we admired on the way up?

Outdoor elitism

In recent years, I’ve seen more evidence that the world of ‘the outdoors’ seems to be gradually drifting away from that fundamental appreciation for nature. Of course, there’s gear, which for some becomes an end to itself – and I love a shiny new waterproof or rucksack as much as the next walker. New ways of experiencing the mountains have emerged, too, from new sports to new ticklists.

I’m not going to tell anyone that they’re enjoying the hills the ‘wrong’ way, but – before the pandemic, at least – these occasional puzzling interactions had begun to add up. I’ve met people on the hill who betrayed indifference or even hostility at the idea of enjoying nature while in the mountains. I once chatted with a climber on a belay ledge in the Northern Corries, and remarked that I’d seen a ptarmigan with half-and-half summer and winter plumage. He looked at me as though I’d grown an extra head. “What the hell’s that got to do with winter climbing?” he’d said. “Everything,” I didn’t dare reply – ice axes are sharp – but I certainly thought it.

A red squirrel spotted on the way up a Scottish hill. Photo: Alex Roddie

We don’t always like to acknowledge that, for some, an element of the outdoors is about setting ourselves above others. Hierarchies abound in the world of mountaineering: higher summits are deemed ‘better’, as are more challenging routes. Even the grading system for rock climbs seems tailored to separate the wheat from the chaff. “How hard do you climb, then? I’m seconding Hard Severe.” “Oh, I’m leading Hard Very Severe.” Of course, every pastime has its own brand of elitism. Even twitchers can get competitive with their lists of birds.

A way of seeing

We all know that scrambling on Great Gable counts as ‘the outdoors’, but what about a gentle walk around a lowland nature reserve with an hour spent doing nothing but birdwatching? Is it on the same spectrum, or is it a different thing altogether? A year ago, I suspect, many hillwalkers would have viewed them as different. Now, after a year of separation from the mountains, the line is fuzzier than ever; and I believe that many people are starting to embrace a broader, more inclusive definition of the outdoors. Perhaps it’s a return to an older way of seeing the mountains.

In the 19th century, pioneering climbers often saw no distinction between mountaineering and nature. In the famous visitors’ book at Pen-y-Pass, pipe-smoking chaps with names like Owen Glynne Jones would list the Alpine herbage they’d spotted while questing up some new Diff-graded gully on Y Lliwedd – often followed by a verse they’d composed on the way down. At its best, outdoor culture has always been a fusion between physical activity, mental challenges, learning about (and helping to protect) the natural world, and even music and poetry. It’s all connected.

One of the most damaging ideas in history is that humans are above nature. But we aren’t. The natural world is more than just a playground or a gym; it’s a home for countless other creatures, and it’s under threat as never before. That includes our mountains. Gear may be more sophisticated than ever, our ways of enjoying the hills more varied; but, for me, a mountain without nature is just a pile of rock, and if you’re obsessing over the summit without stopping to appreciate the wildlife on the way up then you’re missing the wood for the trees.

This is a comment piece reflecting the personal views of the contributor. Want to join the debate? Follow us on Facebook or Twitter.

Subscribe to The Great Outdoors

The Great Outdoors is the UK’s original hiking magazine. We have been inspiring people to explore wild places for more than 40 years.

Through compelling writing, beautifully illustrated stories and eye-catching content, we seek to convey the joy of adventure, the thrill of mountainous and wild environments, and the wonder of the natural world.

Want to read more from us?

- Get three issues of the magazine for £9.99, saving 30% with free UK home delivery.

- Take out a full subscription at just £15 for your first six issues.

- Order the latest issue and get it delivered straight to your door for no extra cost.

- Catch up on content you may have missed by buying individual back issues with free postage and packaging.