For International Mountain Day, we’re highlighting the rapid pace of change in the Swiss Alps

Every 11 December, the United Nations celebrate International Mountain Day. This year their theme is how mountains are under threat from climate change, land degradation, over-exploitation and natural disasters.

We’d like to highlight these important subjects by talking about climate change and mountains – specifically, glacial retreat in Alpine regions. While we can only hope to cover one tiny corner of the world in a short online feature, it’s perhaps enough to show that this is real, it’s happening now, and it’s happening quickly enough to be perceived over the span of a few short years.

By Alex Roddie

In 2007, I made my first visit to the Swiss Alps. My brother James and I went to Zermatt for a couple of weeks and began our Alpine apprenticeship, ticking off some of the easier peaks and getting sunburned on snowfields. We had a great time. Zermatt is no isolated mountain community – and the mountains nearby are certainly not pristine wilderness – but in climbing peaks of 3,000 or 4,000m altitude we got a taste of the inaccessible (or at least the less accessible) and developed skills that could be applied to any mountain range on Earth.

One of the key challenges of the mountains in this area is the fact that you often have to walk over glaciers to get to them. Glaciers are moving rivers of compacted ice, created when snow accumulates to such a depth that it survives for years (or even centuries), metamorphoses to ice, and begins to flow downhill like a plastic. Glaciers used to grace our British hills thousands of years ago, and they are still to be found in higher or colder mountain ranges around the world. For the British mountaineer, the most accessible glaciers are in the European Alps.

Glacier travel is relatively simple but it can be confusing for beginners. The basic rule is to always travel in a pair (or a three), and to use a rope and other basic climbing hardware both to prevent yourself from falling in crevasses and to give you a fighting chance of getting out again. Although standard winter mountaineering techniques such as ice axe and crampon skills also apply, it’s a very different experience to anything in the British hills, and there are greater objective dangers.

One of the mountains we climbed was Stockhorn (3,532m), a long ridge in a spectacular setting, almost entirely surrounded by even higher peaks and glaciated terrain. A small glacier tongue extends almost to the summit. In July 2007, we walked on thick snow and ice along most of the upper part of the ridge and needed ice axe and crampons for most of the ascent. Although some of this snow was left over from the winter and would melt over the rest of the summer, webcam images I saw that September – at the end of the summer melting season – still indicated a good lathering of the white stuff on the ridge.

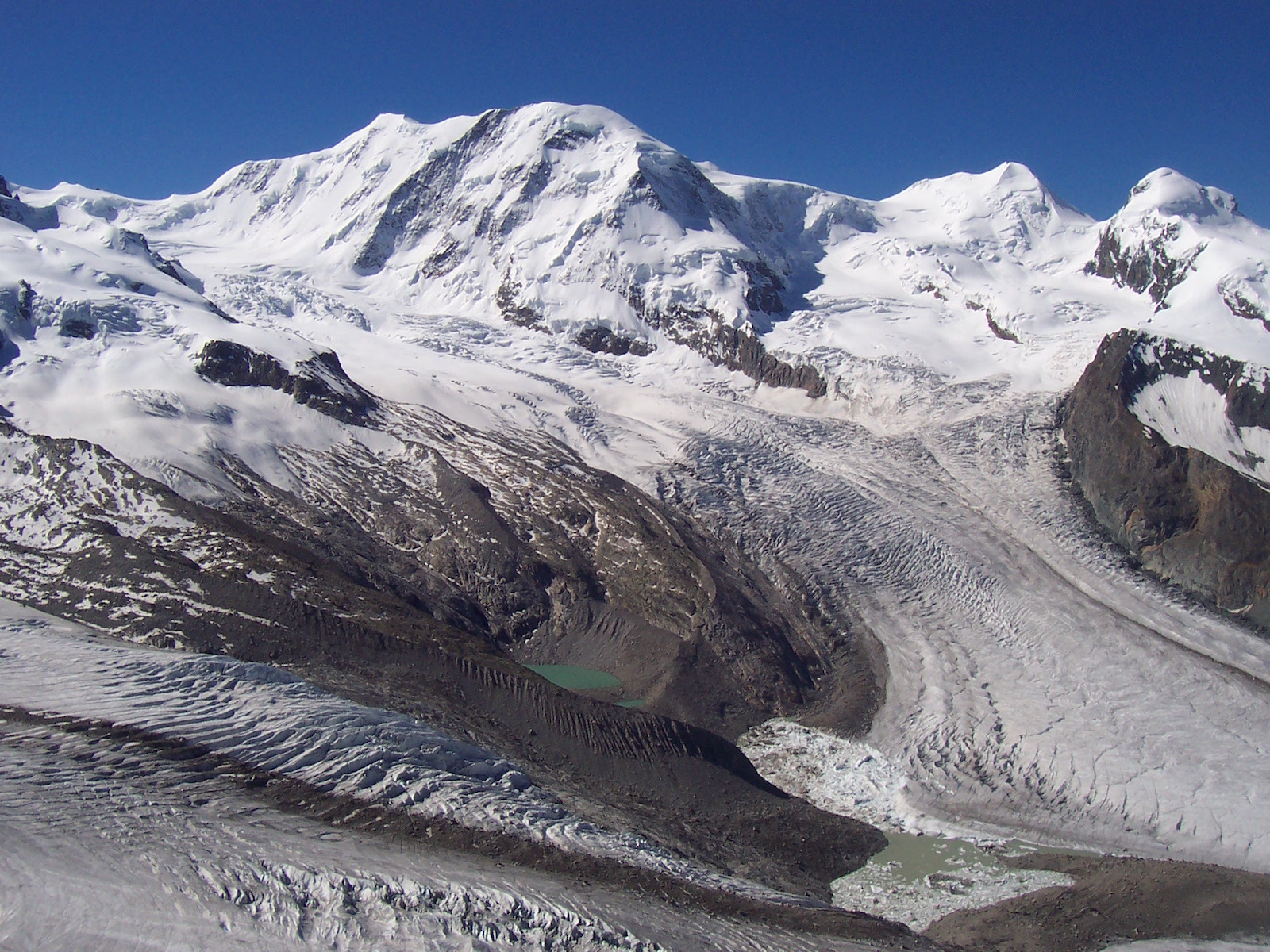

We also had a chance to inspect the Gorner Glacier in the basin to the south. This is one of the biggest glacier systems in the Alps, formed from tributary streams running down from Monte Rosa (the second highest peak in the Alps), Breithorn, Lyskamm, and other nearby mountains. In 2007 there was already strong evidence of glacial retreat: iceberg-filled lakes, bare moraine that would have been ice-covered decades earlier, and long dirt bands indicating erosion of the surrounding mountains. Engravings of a similar view from the 19th century showed the small lake at the foot of Monte Rosa partially filled with ice; today it’s a long way below the glacial tongue extending from Monte Rosa’s summits.

I returned a little over ten years later to climb the same mountain.

In September 2017, Stockhorn was almost entirely snow free. While seasonal variation in snowpack cannot be ignored – the Alps are ‘drier’ in September than in July – I was shocked by the degree to which the surrounding glaciers had dropped and receded. Permanent snowbeds at around the 3,000m contour had shrunk to a fraction of their size a decade earlier or vanished entirely. It’s telling that I only had to put on crampons for about a hundred yards of melting glacier almost at the very top of the mountain.

Looking down onto the Gorner Glacier and Monte Rosa, the scene did not at first appear significantly changed until I looked carefully at the details. Dammed glacial lakes that had been present in 2007, stuffed with icebergs, were gone in 2017 because the ice level had dropped and changed the topography. In a few places, the seracs were visibly smaller and less dense; in others, the downhill tongues of the glaciers had crept a little way uphill.

A similar viewpoint in September 2017. Note that the iceberg-filled lakes in the previous image have gone

This difference was noticeable in only ten years. It saddens me to imagine what these beautiful mountains might look like in another decade.

Obviously, these impressions are far from rigorous science. But don’t take my word for it. Glacial retreat in the European Alps is a well-established fact backed up by a huge body of research, and if you’d like to see it for yourself go no further than the website swissglaciers.org, which includes detailed, high-resolution before/after photos of many Swiss glaciers. The ice loss is obvious to see. The Gorner Glacier is featured here.

Images © Alex Roddie unless otherwise specified