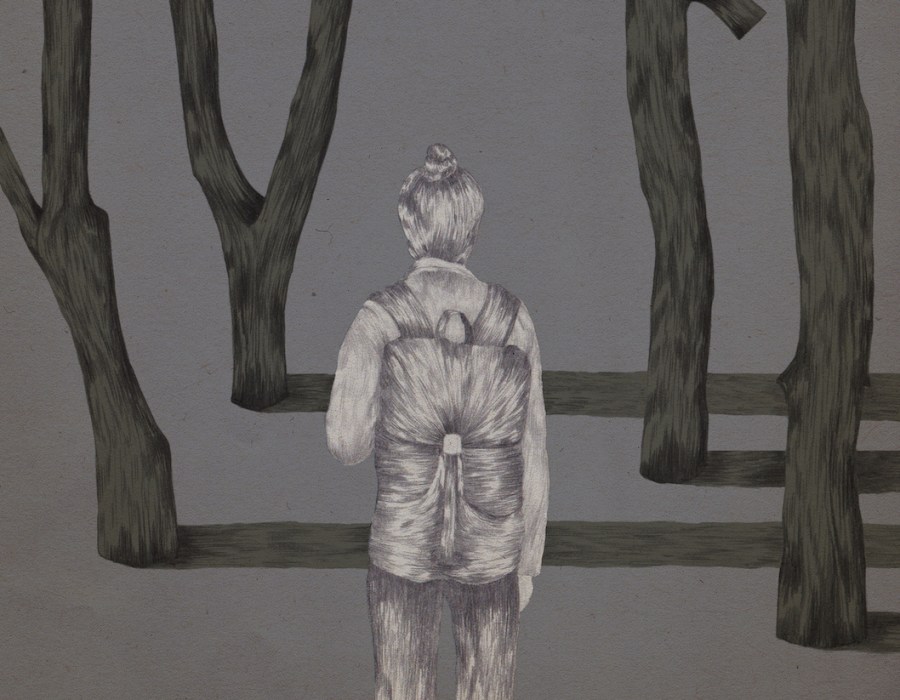

On hearing of Sarah Everard’s murder earlier this year, Lucy Thraves was prompted to explore her lifelong love of walking with a 24-hour hike across the south of England. Why, she asks, does walking alone as a woman still feel like an act of defiance?

“I want to talk to everybody I can as deeply as I can. I want to be able to sleep in an open field, to travel west, to walk freely at night. All is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery.” Sylvia Plath

FOR AS LONG as I can remember, I’ve sought solace in solo walking. I think more clearly, delight in the freedom of solitude, and feel a kind of clarity of purpose that shares a border with deep contentment.

As a child I walked to and from school, using the time to turn over thoughts like stones on a beach. At university, I walked to locate myself in the volatile terrain of early adulthood, through spaces carved out between lectures and nights out. I started working in London and commuted on foot, to try to make

sense of this unruly and chaotic new home; and over this year of lockdowns, I used walking as a way of escaping my room, and to find novelty and the unfamiliar in the newly structureless expanses of day. Walking lets me find myself and lose myself; it allows thoughts to take root and then unearths them.

Politically charged

When Sarah Everard was kidnapped and murdered in March, I and many of my friends were horrified. We’d all walked home from friends’ houses, as she had been doing when abducted; we’d all felt the prickling of fear along the spine at the sound of footsteps behind us. The evening after Sarah’s fate had been confirmed, I went on an evening walk around my local neighbourhood, feeling strange and uncentred. The street-lit pavements were exposing, the shadows of buildings menacing. My senses flared. In the words of Rebecca Solnit, ‘I [thought] like prey’.

It’s not that I was any less at risk prior to Everard’s murder, but the tragedy brought into focus the reasons why a woman walking alone – particularly at night – is a politically charged act. It is always defiant, a declaration of an independence that for centuries has been denied or discouraged.

In her book Wanderlust, Solnit writes that, in Ancient Greece, “in order to keep women ‘private’, or sexually accessible to one man and inaccessible to all others, her whole life would be consigned to the private space of the home that served as a sort of masonry evil.”

For centuries, and still today, when a woman ventures outside, catcalls and leers tell her she is trespassing in a world that isn’t hers: “Street harassment,” writes Rachel Hewitt, “is how men mark out public spaces as their own”. In the late 19th Century, middle-class women who walked for leisure flouted the social conventions “that deemed it entirely improper for a bourgeois lady to roam alone out of doors”. We might think that we’ve moved on; but ‘It was her own fault for walking home so late’, and words to that effect, were all over my Twitter feed in the wake of Everard’s murder.

Power reclaimed

I decided to do my own ‘walk home’ between my mum’s house in Sussex and my home in London. At 65 miles, the challenge stood not just as a declaration of faith in my own physicality, but as an assertion of women’s rights to walk freely and without fear. When I told them my plans, well-meaning friends warned against it; but deciding to walk so far alone in the wake of this tragedy, I felt a sense of power reclaimed. I should add, though, that I had company for the evening and night hours – a concession to the battles this fight has yet to win.

The walk itself felt transgressive in many ways, some of which took me by surprise. As each mile passed, I found myself thinking in ways that seemed shaped by the landscape I moved over, untethering me from the hardened version of myself that other areas of life, notably work, demand. Over those 24 hours, I felt my sense of self unspool and regather, softening to meet the gentle, chalky contours of the South Downs; hardening to push against the concrete surfaces of suburban London. In a society that doesn’t reward vacillation or mutability, leaning into these vicissitudes feels like a rejection of the kind of dogmatic certainty that so often feels necessary to modern life.

The walk itself felt transgressive in many ways, some of which took me by surprise. As each mile passed, I found myself thinking in ways that seemed shaped by the landscape I moved over, untethering me from the hardened version of myself that other areas of life, notably work, demand. Over those 24 hours, I felt my sense of self unspool and regather, softening to meet the gentle, chalky contours of the South Downs; hardening to push against the concrete surfaces of suburban London. In a society that doesn’t reward vacillation or mutability, leaning into these vicissitudes feels like a rejection of the kind of dogmatic certainty that so often feels necessary to modern life.

Towards the end of the walk, night fell, and the accumulated mileage – over 40 by now – began to levy its toll in fatigue. I entered the city’s fringes, inside the M25 but not yet in London proper. Cosy TV dinners and glasses of wine glimpsed through windows seemed otherworldly in their inaccessibility and unlikeliness. Extended solitude made me feel like I was trespassing on these visions of normality, that the rhythms of daily life weren’t mine. This circadian disobedience was a relief after three months of wintry lockdown London, throughout which my whole life was conducted along arbitrary rhythms designed to mimic those from a distant office job era, the structures of a life defined by work.

Multitudes

In her much-quoted essay Street Haunting, which celebrates walking at night, Virginia Woolf writes: “Is the true self neither this nor that, neither here nor there, but something so varied and wandering that it is only when we give rein to its wishes and let it take its way unimpeded that we are indeed ourselves?”

As I finished this walk, in the early hours of the morning, I was left with the impression of having spent time in many different states of mind, moved through many different worlds in the playful light of shifting springtime weather, all in just one day.

In a world in which women are understandably afraid to walk alone, they are denied the opportunity to explore these multitudes freely, held captive by daylight and social convention. Until this changes, walking in all its expansive, liberating glory remains the preserve of men. It’s hard to think freely and clearly when you’re thinking like prey.

This opinion piece was originally published in the October 2021 issue of The Great Outdoors.

Illustration: Claudia Salgueiro