Enjoyment of the outdoors has helped millions of us get through the pandemic. The Great Outdoors editor Carey Davies wonders how it will shape the future as he introduces our new March edition.

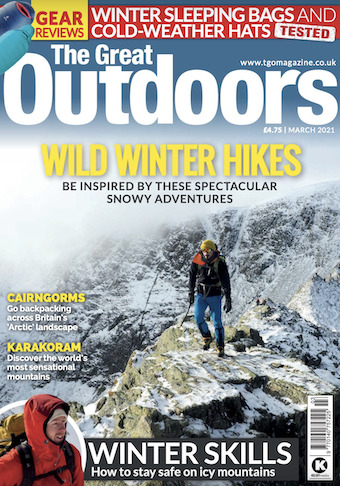

Image: Alex Roddie wild camps on the Cairngorm plateau in the March issue of TGO. Photo: Alex Roddie

Over the last year, it’s become commonplace to talk about the scale-shifting effects of the pandemic: how lockdowns and restrictions, despite their hardships, have made us all more well-acquainted with our immediate localities, and given us a new-found appreciation of what we may have close to hand (which, of course, is a lot more for some than it is for others).

After the first lockdown, with bluebells flaming in the woods and all the intricacy of spring unfolding, it was easy to describe finding “hidden gems” and gaining a “new perspective”. Two further lockdowns (plus about 1,537 ‘tiers’) and the best part of a year later, with the ‘end’ still feeling distant and elusive, and the mountain of wider grief growing bigger by the day, that kind of glass-half-full attitude comes less easily. With our local ways trodden and retrodden countless times, those hidden gems have, in all probability, lost some of their sheen. And, anyway, isn’t it just trite to talk about enjoying the outdoors when something so huge and tragic is unfolding?

It might be, if it weren’t for the fact that the ‘outdoors’ has been central to our collective experience of the pandemic. The local parks; the green islands amidst the urban sprawl; the beauty spots; the shared spaces and common places; the forgotten footpaths; the quiet woods; the riverside hideaways; the endlessly rewarding world of flora and fauna we find in all the above – these are the places that have consistently offered us consolation, escape and everyday freedom while those wider horizons have been off-limits.

I have been further reminded of this during the recent blasts of ‘proper’ winter weather. Snow brings out the fun in people; and on my recent lockdown-permitted walks and runs it has struck me how much more buoyant everyone seemed as they sledged down slopes, engaged in snowball combat or just marvelled at a world turned monochrome and filigreed with white. Once again, the outdoors was one of the few things giving people a reason to feel happy.

It feels apt, then, that the big theme of the March issue of The Great Outdoors is the joy, spectacle and drama of winter. Of course, the wild, mountainous environments we feature in the magazine remain in the realm of the hypothetical for many of us right now, and it all comes with the usual caveat: respect the restrictions, and treat all this as inspiration for the future.

At times I have even seen a glimmer of something hopeful in it all: a future where this experience leaves a big enough cultural impression to fundamentally reshape our approach to land, landscapes and nature, finally recognising the central importance they have to our health and happiness. But perhaps that’s a forlorn hope: despite the low risk of transmission in open spaces and the clear health benefits of outdoor recreation, some national parks are far more interested in stopping access, while the government is pushing ahead with its plans to criminalise trespass, which if passed will further alienate people from open enjoyment of the land.

Once thing certainly hasn’t changed: if we believe in things like a greater rightto roam, vibrant ecosystems, better infrastructure and a more enlightened environmental culture – the outdoor world we all deserve – we’re going to have to fight for them.

Want to read more from us?

- Get three issues of the magazine for £9.99, saving 30% with free UK home delivery.

- Take out a full subscription at just £15 for your first six issues.

- Order the latest issue and get it delivered straight to your door for no extra cost.

- Catch up on content you may have missed by buying individual back issues with free postage and packaging.