Comedian and hillwalker Ed Byrne could do with improving his navigation skills. We sent him out with an instructor for a bit of map-and-compass work

Ed Byrne is currently touring Britain with his new show, Spoiler Alert, as part of which he shares some hilarious insights into the trips he’s made into the hills for The Great Outdoors magazine. As it’s National Map Reading Week this week, here’s his very first column – on basic navigation.

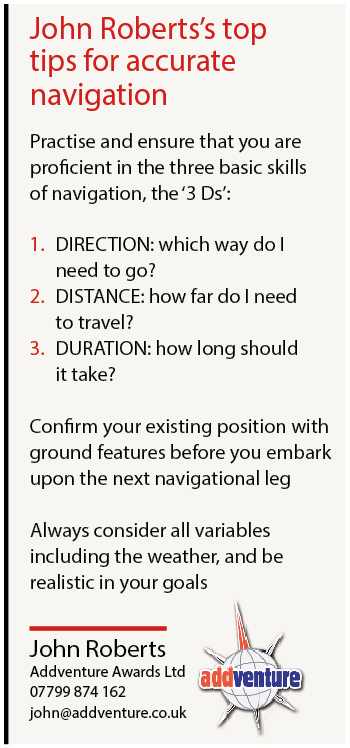

I meet John Roberts, my instructor for the day, in the car park at Penistone Hill in West Yorkshire. My refresher course in Basic Navigation is to take place deep in Brontë country on the very moors on which Wuthering Heights was set. Hopefully, my relationship with John won’t end up as complex and fraught as some of those in the book. It would be a shame if a simple lesson in navigation resulted in one of us spiralling into madness.

Luckily, John is a friendly and diplomatic fellow. I discover this early on when, having established where we are on the map and where some obvious features are in relation to us, John identifies a trig point on the map and says: “So, point in the direction of this trig point.” “Um, that would be over there,” I say, pointing directly east. “Yes. That’s right. It’s over there,” says John, pointing directly north-east. Clearly, this is a man who’s not going to let a trifling 45 degrees get in the way of a friendship.

Picnickers passed us by thinking we’d somehow gotten ourselves lost between the car park and the signposted public footpath

An important fundamental of navigation is estimating distance, John tells me. He points towards a speed limit sign on a road below us. “How far away would you say that is?” “About a hundred metres?” I venture. “It’s a good bit further than that,” says John. “That’s a good 400 metres away.” Humbled by my appalling ability to judge distance, we decide to measure out 100 metres in paces. This is one of those things I’ve always meant to do but for some reason never got round to. Any walker worth their salt should know how many times their left foot hits the ground over 100 metres. It’s a very handy piece of information and I’m ashamed to admit that up until now I hadn’t a clue. Two hundred metres of pacing later and I discover I take 70 double steps per 100m. That’s a handy number. I pity those people with 67 or 73 steps per 100m. The maths must be a nightmare! 70. Good round number. Yay me!

With this nugget of info fresh in my head, John and I head along the footpath known as Brontë Way. As we go John gives me a lesson in micro-navigation by pointing out various features such as walls and houses on the map, measuring the distance between them using the compass as a rule, converting the distance into strides and counting them off as we walk along. It’s quite an eye-opener to demonstrate just how painstakingly accurate an OS map is and also how reliable the length of your stride can be as a navigational tool.

Speaking of tools, I reckoned we looked like a right pair with our rucksacks and gaiters on, consulting map and compass as dog walkers and picnickers passed us by thinking we’d somehow gotten ourselves lost between the car park and the signposted public footpath. I kept trying to nod to people as if to say: “We know where we are. This is merely an exercise,” but that’s a lot of information to get across in a nod.

John and I wend our merry way down Brontë Way for a few kilometres and then head up onto the moors where we are to try a few exercises in medium- to long-distance navigation. I practise taking some compass bearings and, satisfied that I seem to know what I’m doing with that, John suggests I try to triangulate our position using the map and compass. Using three fairly obvious features – an old building, the top of a small hill and the corner of a distant wood – I set about doing just that.

Anyone who’s ever triangulated their position on a map in this manner will know that you normally end up with three intersecting lines forming a small triangle which represents the area in which you’re located. I am very proud to say that I ended up with three lines intersecting at exactly the same point. Unfortunately, that point was about half a kilometre from where we were standing. Put it this way: if I was Heathcliff and I’d arranged to meet Catherine on the moors, we’d have missed each other. John said that my technique was pretty sound. I just needed a bit more practice. There’s that diplomatic attitude again.

“Um, that would be over there,” I say pointing directly east. “Yes, that’s right. It’s over there,” says John, pointing directly north-east

Next up, an exercise in navigating to a point on the map. John selects a trig point, which I take a bearing on, and then he asks me to work out how long it will take to get there. Assuming we’re walking 4km an hour plus one minute for every contour line we cross, I calculate a walking time of 20 minutes. “Right, let’s go,” says John and we set off along our bearing for what should be 20 minutes.

At this point I make a mistake I’ve been making with alarming regularity for most of my professional career. As a comedian performing in comedy clubs, more often than not, you’re expected to perform for 20 minutes. It’s quite important that as a professional comic you stick to this time. Any less and the club owner hasn’t gotten his money’s worth from you. Any more and the other people on the bill think you’re a stage hog. Also, every extra minute the show goes on is an extra minute the staff have to work so it’s important for all concerned that you do your allotted time, no more, no less. However, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been stood on a stage, looked at my watch to see how long I’ve done, only to realise that I didn’t look at my watch as I took to the stage. “Hmm!” I would say aloud to the audience. “I see by my watch that it is ten past nine. That information would be very useful to me if I had any idea what time it was when I actually started my act, but as I forgot to check…” This admission of stupidity would generally raise a chuckle, but in my mind there would be a slight panic at the fact that I genuinely had no idea how long I had still to do.

At this point I make a mistake I’ve been making with alarming regularity for most of my professional career. As a comedian performing in comedy clubs, more often than not, you’re expected to perform for 20 minutes. It’s quite important that as a professional comic you stick to this time. Any less and the club owner hasn’t gotten his money’s worth from you. Any more and the other people on the bill think you’re a stage hog. Also, every extra minute the show goes on is an extra minute the staff have to work so it’s important for all concerned that you do your allotted time, no more, no less. However, I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been stood on a stage, looked at my watch to see how long I’ve done, only to realise that I didn’t look at my watch as I took to the stage. “Hmm!” I would say aloud to the audience. “I see by my watch that it is ten past nine. That information would be very useful to me if I had any idea what time it was when I actually started my act, but as I forgot to check…” This admission of stupidity would generally raise a chuckle, but in my mind there would be a slight panic at the fact that I genuinely had no idea how long I had still to do.

This was exactly what happened as we set off for the trig point. I knew it would take us 20 minutes, but I didn’t take a note of the time as we started to walk. What a doofus! Luckily John said, “Well, it’s 1.45 now. So, we should be there by five past two.” And I’m sure we would have been, had I not allowed us to wander off course.

We spent the next two hours navigating to spots on the map and, I have to admit, by the end of the day I was getting pretty good at it. The most useful tip was that of turning back to face your starting point and taking a reverse bearing to ensure that you’re still on course: a very simple technique that I had just never picked up before. With a bit of practice my map-and-compass skills became vastly improved and we decided to plot a course back to the car park.

As we approached our start/finish point I gestured towards the speed limit sign from the beginning of the day and said, with a renewed sense of confidence: “I reckon that sign is 300 metres away.” John looked over at it and said, grimly: “I think it’s closer to 400 metres away.” Clearly, I still have a long way to go. Just don’t ask me exactly how long!

addventure.co.uk

All images © Dave Willis

This feature was first printed in The Great Outdoors, July 2011.