Mountain photographer Dougie Cunningham talks Scottish mountains, the changing nature of landscape photography, and the benefits of owning a camper van

In the December 2017 issue of The Great Outdoors, we asked Dougie Cunningham of Leading Lines Photography to share with us some of his top mountain images. We got back in touch with Dougie to find out more about his marathon Scottish photography guidebook project, and to show some more of his exceptional photographs.

Please introduce yourself. Who are you and what do you do?

Hello! I’m Dougie Cunningham, a self-employed photographer based in Glasgow and working throughout Scotland. In addition to wedding and event photography, I’m lucky enough to also have the opportunity to work in the mountains too, shooting and occasionally writing for magazines and other publications. Over the last couple of years, my main focus has been on producing a guidebook to Scotland written specifically for photographers.

Tell us about your new photographic guidebook. How can it help mountain photographers?

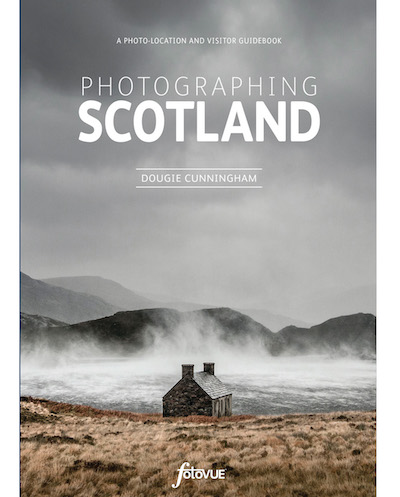

Photographing Scotland by Dougie Cunningham

Photography has become massively popular, and I think more and more people are turning to it as a medium and a means for enjoying the outdoors. More and more walkers are putting time and effort into taking the best photographs they can while they are out on the hill, but there are also many people enjoying photography as their primary motivation for exploring the countryside. There are plenty of walking guidebooks for Scotland, but Photographing Scotland is aimed at those people who want to capture the best possible images rather than chase the summits or specific routes in the hills.

With that in mind, there’s perhaps more variety than many guides may offer. Some places are essentially park and shoot, while most involve at least a short walk. There are even a few mountain routes described for those wanting to venture further into the hills. All the locations have parking and access information to make it as easy as possible for people to visit, and have suggested times and conditions to help plan a trip. I’ve also tried really hard not to make the book too prescriptive, and to encourage people to explore beyond the most obvious spots.

How did you come to land this dream project?

I was incredibly lucky to be asked to work on this project! I regularly photograph the Keswick Mountain Festival, often working alongside a local photographer called Stuart Holmes. He wrote the fotoVUE guide to the Lake District (which is excellent and about to be reprinted), and introduced me to the publisher one year. By a stroke of good fortune I had an exhibition up and we met for a coffee to talk over the project and how we both saw it taking shape. It must have gone well, because a few months later it was all signed and sealed, and we’ve never looked back!

Tell us about some of your top moments.

It’s been an epic project to work on, in the most literal sense! From start to finish it was 4.5 years of research and travel around Scotland. There have been countless roadtrips to every corner of the country, staying in my wee camper van for stretches of up to a month at a time. Walking off the hill in the dark and arriving back at a comfortable bed that feels like home… what’s not to like!

There are specific moments I’ll never forget, but there was also just the continual feeling of discovery throughout the whole process. I had arrogantly thought that I knew Scotland fairly well when I started, but I’ve learned more than I thought possible over the last few years. It’s a clichéd, hackneyed thing to say, but it really has been an incredibly journey.

There must have been low points too. Any moments when you wondered what on Earth you were doing?

I can’t deny that there were a few! I love being away and being up in the mountains on my own, but I confess that there were times when I craved a bit of company during the longer trips. I would also say that being too ill to drive home and being stuck in the van for a few days in the middle of winter was not a lot of fun. My first van wasn’t hugely reliable either, and I’ve broken down in some very… inconvenient places!

Looking back now, I think the most testing aspect of the project was more mundane. The project was a huge commitment in time and resources. Maintaining momentum while trying to keep my business running and life on track was sometimes pretty difficult.

In your feature published in the December 2017 issue of The Great Outdoors, you mention that working on the book provided motivation to get out and take a chance on the weather – a gamble that sometimes paid off. Did this experience change your opinion of other mountain ‘projects’ such as ticking off the Munros?

I’d always scoffed slightly at people working towards the Munros; at the end of the day, it’s an arbitrary classification and no measure of the quality of the mountain, so why prioritise mountains you’ve no particular interest in just because they happen to tick a certain box? I understand it now, though. Having made a personal commitment to a long-term goal you feel like you’re letting yourself down if you don’t get out when you have the opportunity. It gives you that little extra drive to get out on a day or a weekend when you’re maybe a little tired or the weather isn’t looking great or whatever. And once you’re out there you almost never regret it.

I’m a complete convert. I don’t think I’ll be starting a round, but I can understand the attraction now and I’ll definitely find another project.

How do you see outdoor photography evolving over the coming years? Do you think it’s becoming easier or more difficult to create meaningful images, and why?

That’s a difficult question! The idea of a ‘meaningful image’ is a tricky thing in itself. I think that people’s expectations from photography have gone up – we are exposed to so many images constantly that a photograph has to be something pretty incredible to be memorable these days. On the other hand, everyone always has a camera to hand too, and if you spend enough time in the hills you will inevitably come across something quite special at some point. Whether you’re the next Joe Cornish or you’re snapping away on your camera phone, these personal memories are so much more meaningful for the simple fact that they are your own.

In broader terms, while I don’t think that ‘traditional’ still photography is ever going to lose its appeal, I think it’s becoming augmented by newer technology and techniques too. Video is perhaps the obvious contender, but it takes considerable time, effort and skill to edit a good video after the fact. What I think we’ll see is the rise of things like 360° images (‘bubbles’), 3D and the likes, which can be viewed online or with virtual reality headsets.

How do you think photo location guidebooks will affect the images we see published in print and shared on social media? Any risk of increasing the honeypot effect – or do you believe it will only enhance creativity as more experienced photographers spread their wings and discover new locations?

The honeypot effect has already run rampant through the rise of social media. This issue was always at the front of my mind while I researched and wrote the book. Places like the Quiraing or Elgol are prime examples of how I hope that the book will actually help people get past the most obvious features at the most popular locations. I remember turning up at Elgol one evening and seeing about 15 photographers all down on the rocks at the end of the beach, jockeying for position… I went the other way along the coast and had a mile of incredible features all to myself. It’s crazy.

I’ve heard it argued that people just want to recreate images they’ve seen elsewhere, but that seems a little cynical to me. We’re not all lucky enough to live on the doorstep of these iconic locations, and I think people tend to head for the familiar and easily recognised features simply to get the most out of the limited time they have during a visit. If you’ve only one night at Elgol, then it seems risky to go to opposite direction to where you know there’s a good photograph to be had. This is where I hope that the guide helps – I’ve done the scouting already. I’ve spent the time exploring and I’ve tried to point people to alternatives when they’re worthwhile.

There’s a simple joy to be had in finding something for yourself, and when people to break away from the honeypot it brings a new level of enjoyment and satisfaction to their photography. I made a conscious effort to encourage people to think for themselves and explore a little further than they might otherwise have done.

What were the top items of kit you relied on for the duration of the project? Did anything last the full five years?

A really good tripod makes a difference, particularly having the fine control possible through a geared head. It’s a heavy thing though, so I stick with a lighter set of carbon legs and a three-way head if I’m hoping to go up into the mountains. There wasn’t much photographic kit that saw the entire project through completely unscathed, and most things needed a good service at some point.

A good head torch is one of the most indispensable bits of outdoor kit. You spend a lot of time walking in the dark, either before sunrise or after sunset.

I also don’t think that I could have finished the project without my camper van. Having a decent bed to collapse into at the end of the day, and space to sort and dry kit while on the road, made all the difference in the world.

Any more big mountain photography projects on the horizon?

I’ve decided what my next big photography project is going to be, but I’ll keep that a wee secret for now…

As for the mountains… I’m going to try and take in as many of the classic ridges as I can over the next couple of years. I might even take along some friends, just for the banter! I’ve spent a lot of time along in the hills recently, and I think I’m going to focus a little more on photographing people in the hills for a while; walkers, climbers, campers… Not that I’ll stop shooting straight landscapes too!

Photographing Scotland: a photo-location and visitor guidebook by Dougie Cunningham is out now (fotoVUE, £27.99)

All images © Dougie Cunningham. Header image: Buachaille Etive Mor