I’ve had ME since I was 21. Growing up on a hillside, at the far end of the Pentlands, my interest in mountain culture coincided with a catastrophic collapse into chronic illness. Overnight I could barely walk. For 30 years, working as a poet and artist, I have felt driven to make work in landscapes – The Peak District, Cairngorms, and Cuillins – where my limited walking made me a natural exile. Many times I relapsed for days from going too far. Then, slowly, I found that creativity gave me ways to be, and even belong, in the hills. Rather than hiking, I learnt to sit, look, and rest.

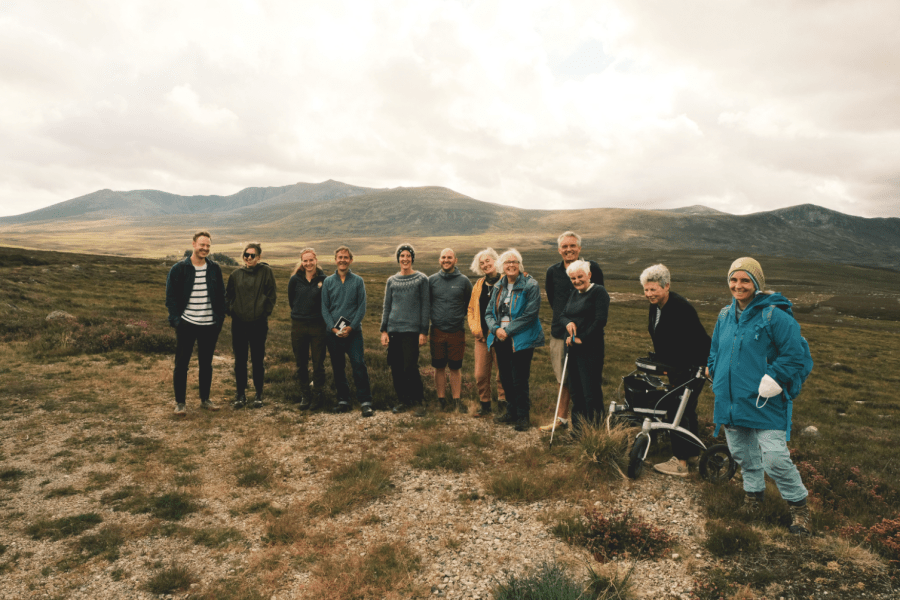

Main image: People with terminal cancer, MS, Long Covid and partial sight gather for a Day of Access at Balmoral Estate | Credit: Sam MacDiarmid

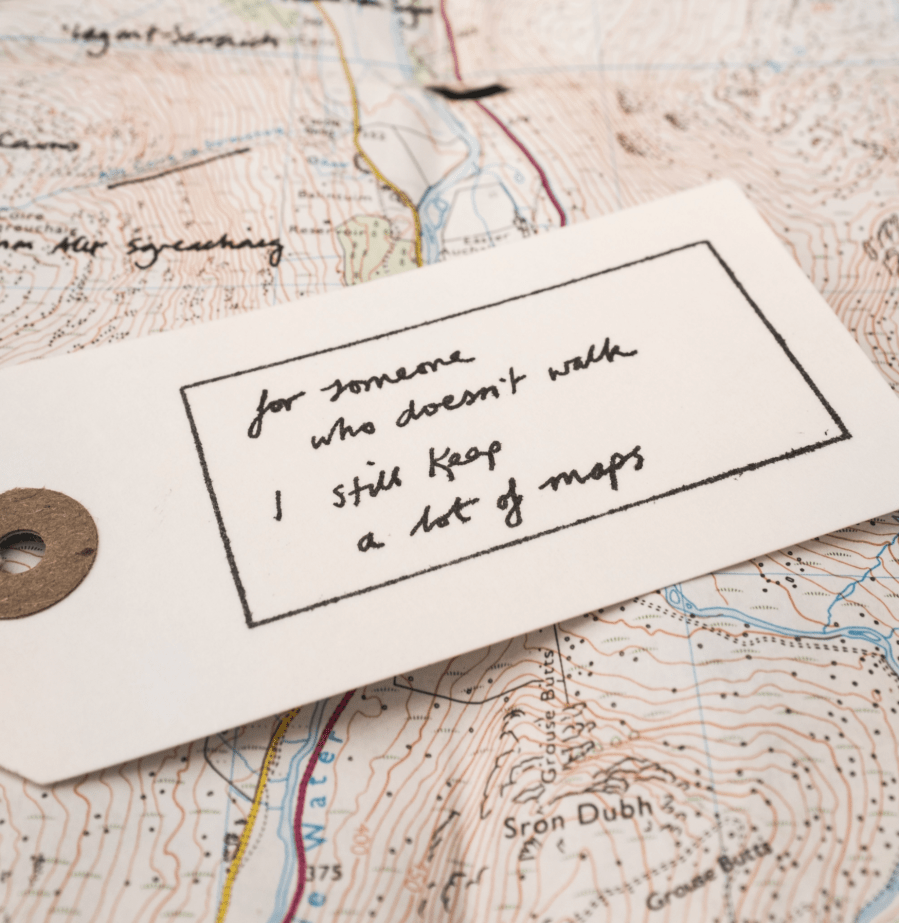

Gaelic place names became my guide to the hillside beyond. I began to read the landscape and write out the names on ‘poem labels’, aware that the unfamiliar colour names were tags for montane ecology, describing it as it had been, is, and could be again. Names told me where there used to be woods, where people used to summer in shieling huts, where there were springs and berry patches in times when dwelling in the hills meant more than hiking.

As an expert ‘not-walker’, I’ve made books celebrating mountain culture, including the first ‘place-aware’ guide to the Cairngorms. What I had never done, until 28 July, 2017, was to reach the summit of a mountain. That was the day we had to transport sound recordist Chris Watson’s gear up to Coire ne Feadaige (‘golden plover corrie’) on Càrn Mòr (‘big cairn’).

We were making the world’s first ‘Fauna Jukebox’, for the Fife Arms, which would involve us navigating our way to a dozen place-names. Their meanings told us where to look out for rutting stags, mewling eagles, hissy-fit wildcats and howling wolves, and how to map sounds as a record of species survivals and extinctions.

Best of all, I got to hitch a ride up My First Mountain. Sitting on the weave of shiny moorgrass, I marvelled at this first sight of mountains without end, and the concept of ‘Day of Access’ was born. Initially, the project supported creative access to wild nature for people with constrained walking and chronic fatigue. It relied on estate Land Rovers and hill tracks, and the help of private and public landowners. Why was this kind of solidarity unheard of?

At one event someone recounted a laird who refused to make a gate accessible, saying, ‘but what would a disabled person do up there?’ In that imaginative void there resounds the artificial limits we’ve set upon what hills are, and what they are for. As the project evolved, the focus extended to vulnerability and how to heal our sense of belonging.

It was a literal highpoint to arrange for a pal with terminal cancer to reach the summit of Càrn an Tuirc, (‘boar cairn’), driven by an Invercauld forester who was surveying dotterel. This overlap between human and ecological vulnerability revealed another neglected truth about wild landscapes: we now recognise them as fragile, characterised by bryophytes, mosses, and wool willows hugging the ground as much as by the sublime peaks of the old climbing culture.

Now I understood that the project was a way to free the wisdom that exists within limitations. Need disabled access be identified with repeating things the able-bodied can do, like wheelchair abseiling?

As an alternative, I began to explore ‘creative adaptation’; the innovative changes stimulated by challenging mental and physical conditions, such as chronic fatigue or pain. I was circling back on myself, to the days when I learnt to replace hiking with viewing and first became aware of ‘microtonal’ landscapes – meaning the wee habitats and territories which place names and flora and fauna define.

I invited writer and forager Tamara Colchester to guide people with chronic arthritis on a ‘plant listening’ forage at Culbin Sands. They learnt how a niche in the landscape holds infinite interest – in mushrooms, pine-needle tea, and juniper – and is just as wild as scree or upland moors. At another event we were guided by a deaf Gaelic singer, Evie Waddell, to translate Gaelic hill names into British Sign Language, becoming the hills with our hands.

Alison, an elderly woman from Braemar with very limited sight, has been on three events. It’s a privilege to walk with her and learn.

“When I became blind, I lost so many friends,” she told me. “Some tried to lead me, others left me at a loss; it’s rare to know how to walk with a faltering pace.” We have learnt from her faltering, noticing the tree roots running like thick veins across the paths in Ballochbuie, and how, “secure among friends, green is what I see of the trees around me, as the breeze disperses a warm fragrance in waves. The track’s narrow way is lit by Hayden’s electric yellow trainers: sight is not the only sense.”

That day we were driven by Balmoral estate nature rangers to the Honka Hut in the middle of an ancient pinewood. We imagined every hill and wood could have a hut of healing where we could stay. When you cease to see limits as handicaps and listen to the acute perceptions of people who cannot hike or climb, the meanings wildness expands.

A friend once told me about a mountain climber who was dying of cancer. Hating the antiseptic hospital, longing for the hills, his bed became an improvised shelter of bobbled blankets and screens. That story affirms a founding truth of the ‘day of access’ project: the housebound shouldn’t be restricted to an interior world – the mountains belong to them, and they belong to mountains. It just takes imagination. Take a peek at your knees bent under a tartan bedcover and you can choose to see a Highland ridge.

Read more about the Day of Access at dayofaccess.co.uk.