Main image: The summit of Reither Spitze on the Karwendel Höhenweg in Tyrol | Credit: Alex Roddie

I sometimes wonder if there are two walkers in me, tussling for dominance. There is the man who likes to go fast: a creature of firm trails and Alpine sunshine, a light pack and big miles, dodgy bivouacs, and shoestring budgets. Then there’s the guy who appreciates a slower, more considered pace, fond of midday siestas, lazy starts and early finishes. The two styles don’t have to be mutually exclusive but accommodating them both can require some give and take. Most of the time, I am the grubby ultralighter, and the slow-and-steady connoisseur doesn’t get much of a look in. But, just sometimes, it all comes together to show me just what I’ve been missing.

An Alpine Coda

My summer that year had been one to remember, testing my ultralight skills in the lightning-strafed cirques of France’s Mercantour National Park. Having fed that particular rat, I wanted more. Then, out of the blue, Visit Tirol got in touch: “How would you like to come and hike the Karwendel Höhenweg in Austria? A nice, chilled-out hut tour with short days, good food, and lovely mountain views.”

It did sound nice, but it also sounded a lot slower than the Alpine coda I’d been yearning for. On the other hand, was I seriously going to turn down an offer like that?

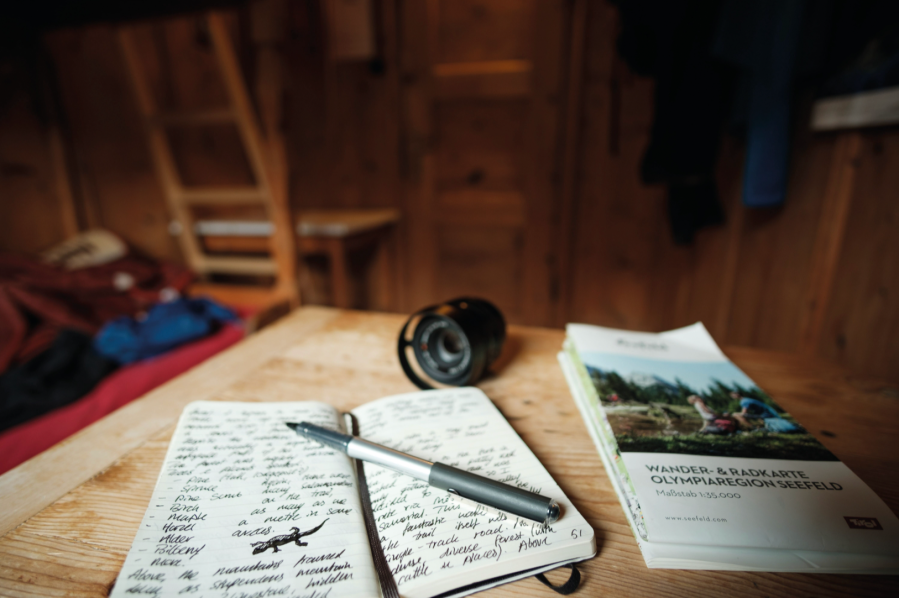

It had been years since my last hut tour. There’s a lot to like about the culture of mountain huts throughout the Alps – it’s a vast network of well-situated, well-appointed refuges that makes long-distance walking a lot more comfortable and accessible. And although the ultralighter in me prefers the idea of a lonely summit camp, staying in huts can save a lot of pack weight – all you need are your clothes and a sleeping bag liner, making room for more luxuries.

Still, the experience is a lot more structured. You can’t just walk as far as you like and sleep where you like; you have to plan ahead, especially in the busy summer season. I’ll admit, I was craving more freedom on the long climb uphill into the mountains. I began in the village of Reith bei Seefeld, west of Innsbruck, and was plunged directly into dense pine forest without much chance of a view for an hour or more.

My schedule – yes, I was hiking to a schedule – said that I was expected at the Nördlinger Hütte at a certain time that evening. This had put me in a negative frame of mind from the start.

Although warm sunshine had greeted my arrival in Tirol, and I’d marvelled at the vast white limestone walls of the Karwendel mountains towering above me from the valley, the forecast for the next few days was bleak: wind, rain, and low cloud. Combined with some very leisurely day stages (some shorter than five miles), at this point I was far from certain that this was the trail for me. I imagined hours twiddling my thumbs in deserted refuges, wishing I were making quicker progress through sunnier, drier mountains elsewhere.

Herr Brexit

That first night at Nördlinger Hütte (2,239m) helped to start changing my mind. Views had opened up an hour or two before reaching this high vantage point up on the ridge, and I was astounded by the battlemented crest of spires and pinnacles that spread out in front of me – some of the most brashly exaggerated mountain forms I’d seen anywhere.

Hot sunshine still beat down on dry, friendly trails. This is a bit more like it, I thought as I roamed to and fro on the ridge, taking far more time with my photography than I usually would. I was intrigued, too, by the thickets of dwarf pine scrub that carpeted the mountains, textured like velvet when seen from a distance. This place felt different and exciting and new.

After checking in, and an afternoon ascent of the rocky summit of Reither Spitze (2,374m) directly above the hut for even better views, I enjoyed a beer on the balcony and conversation with a group of German hikers. As soon as they heard my English accent, there was a chorus of “Ah, it is Herr Brexit!” – but with a generous dollop of humour. They told me none of the other English hikers they’d met would admit to voting for it either. The other thing about the alpine hut experience is the comraderie. That night in the hut we were all mountain enthusiasts brought together by a shared passion for high, wild places.

Thunder rumbled outside over dinner and the first raindrops soon began to rattle against the windows. The hut guardian, Tobias, took me to one side after dessert and advised me to team up with the German group for the stage to Solsteinhaus, the next hut; the trail crossed two high, exposed passes and a good deal of loose and rocky terrain. My new friends agreed, although the good-natured ribbing continued: “We were a group of twelve before. Now we will be unlucky thirteen!”

The Day of Salamanders

Despite covering a mere four miles, day two wasn’t the pushover I’d expected. If I’d planned own schedule for this trip, I’d probably have merged days two and three together, avoiding Solstenhaus, but I’d have missed a memorable hut evening, fantastic food, and some of the intriguing details to be found at my feet along the way.

Torrential rain never let up all morning. Some of my German friends hiked with umbrellas, some with ponchos, some with traditional waterproofs; we all got soaked. I took turns walking with several of them as we negotiated the relentless stony terrain of first one pass, then a traverse along the northern flank of the ridge, then another pass.

Under our shoes, shifting scree; above us, crazy rock towers rising into the murk, lending a fantasy ambience to the walk. We helped each other over rock steps and loose gullies. And we often paused to appreciate the black Alpine salamanders that had come out in the rain, waddling over the rocks with their delicate little hands and feet: water-jewelled souls that I was terrified of stepping on accidentally.

Everyone in the group went at their own pace, leading to a procession strung out over a kilometre or more. I thought I’d feel impatient, but I enjoyed the varying conversations and perspectives. I learned that they were a group of colleagues from Bosch who met up to go hut trekking every summer. They asked me why I often preferred to wild camp instead of stay in huts.

“When we go to the mountains, it is a holiday. We like to be able to relax as well as challenge ourselves. The huts let us do that. Why carry a heavier backpack with camping gear and then spend more time wet and cold?”

At Solsteinhaus we were greeted by a brisk log fire and even brisker glasses of Schnapps, which went straight to my head after a few hours in the sluicing rain. Robert, the guardian, explained that Solsteinhaus – a much larger hut than Nördlinger – would usually be full at this time of year, but he’d had many cancellations due to the weather. “You’ll have most of the common room to yourselves tonight.”

That evening, we clustered around the stove, swapping stories. I ate until I could eat no more. Someone asked me if I’d really prefer to be out there in the howling wind under a flimsy tarp, and I couldn’t in all honesty say that I would.

Seasoned Solitude

After Solsteinhaus, my friends decided to head back to the valley a different way while I continued along the Höhenweg – although not for long. There was no end to the bad weather in sight. The guardian warned me that the next stage was by far the most difficult and exposed. A look at the map revealed a low-level alternative through the forests that looked worthwhile, though.

If ever there were a day to go slow and appreciate the marvellous details of nature, this was it. Rain, cloud, a cold bite to the air, and the first tinge of autumn colours in the forest – colours all the more vivid in the rain. I relished the coppery edges of birch and beech, in the first of the fern fronds turning away from summer greens, in the subtle tipping over of feel from summer to summer-autumn that can’t be directly quantified. And in solitude again. But solitude seasoned by the richness of the company I had just left behind.

This foul-weather alternative was no second prize. The woods rewarded me with more salamanders as well as frogs, fungi, lichens and more to enjoy at my leisure – and I knew that I could stop as often as I wanted. I arrived at Pfeishütte feeling deeply relaxed and utterly unconcerned that I was once again soaked to the skin. There would be a drying room, a warm fire and warm food; what did a little rain matter?

“Achtung! Steinschlag!”

The next stage looked spikier on the map and I knew that there was no way around it. Fortunately, the worst of the weather seemed to be behind me now, although thick cloud stubbornly clung around the peaks, robbing me of those grand views I’d been told about on this section.

At 2,215m, the Stempeljoch is a serious pass, and its landscape of scree on a grand scale made the Great Stone Chute on Skye look like a gully in the Chilterns. After climbing loose ground to the col, I found myself on the brink of a vast cirque entirely filled with shattered limestone, it’s scale confounding comprehension. Trails snaked down and across it, propped up by bits of wood hammered into the ever-shifting surface.

The boiling cloud once again lent everything an air of high drama. Things were about to kick into a higher gear; maybe this would be the dose of mountain adrenaline I’d been looking for. A sign in front of me warned: “Achtung! Steinschlag!” And, to reinforce the point, there were even little memorial plaques to climbers who had been killed by stonefall here over the decades.

The Höhenweg cut directly across the wildest and most exposed mountain terrain. This section is known as the Wilde-Bande-Steig, constructed in the 19th century by Innsbruck’s first Alpine club, the Alpine Gesellschaft “Wilde Bande”. Exposed ledges, iron cables and rungs protecting the steepest sections, and a real sense of adventure provided a delicious contrast to the previous day’s forest zen.

I even found a snow patch, embedded like a limpet in a V-shaped chasm at the base of a crag. As is so often the case, the trail wasn’t as hard as it looked – and I appreciated the luxury of being able to traverse such committing terrain without the stress of finding somewhere to bivvy.

The trail granted me two more excellent days after this. Two more days of raindrop-beaded pine needles, mountain walls stretching high into the mist, buzzards gliding on thermals, the ring of cowbells in the meadow, and delight in the nature all around me. I won’t say that my urge to go faster ever disappeared, but I stopped feeling that I was somehow doing things the “wrong” way for only walking a few miles each day.

Looking back, the Karwendel Höhenweg seems to hold more moments of surprise, discovery and joy than any other trip of its length. Is that because a schedule forced me to slow down? Is it because the weather didn’t allow more than a handful of glimpses of those grander views, instead concentrating my attention on other things just as wondrous but perhaps less obvious?

Or is it because I’d had my preconceptions challenged, shifting from negativity to a willingness to embrace a new kind of adventure? Whatever the reason – and I think it’s a mix of them all – Karwendel was a watershed moment for me. I still love fast and light, but I look forward to slower trips as well, because I find myself noticing more. Sometimes appreciating more too.

About the Karwendel Höhenweg

- Total distance: 63km / 39 miles

- Time: 3–6 days

- Total ascent: around 3,400m (11,000ft)

- Best time of year: June to September

- Starting point: Reith bei Seefeld, Austria

- Finishing point: Scharnitz, Austria

- Accommodation: Alpine huts; booking essential (camping is not permitted)

- Transport: both ends of the trail are well served by public transport to and from Innsbruck (train and bus); see karwendel-hoehenweg.at for more information. It is also possible to join and leave the route from any of the mountain huts

- Further information: visittirol.co.uk, seefeld.com, and the trail’s official website, karwendel-hoehenweg.at

Am I experienced enough for the Karwendel Höhenweg?

The Karwendel Höhenweg is a challenging hike. Although it is well waymarked, many of the trails are black graded, which means that they are very steep, exposed, loose, and involve short sections of easy scrambling (often protected by ironwork such as rungs, steps, or cables).

It isn’t a trail for beginners, but experienced walkers in the more challenging Scottish hills will feel right at home. Early in the season, snow may still be encountered on sections of the route, requiring the use of ice axe and crampons. Fresh snow can fall at any time of year.

The Alpine salamander

The Alpine salamander, Salamandra atra, is a relative of the newts to be found in the UK. This striking creature has glistening black skin and is a gentle presence in the mountains and forests of the eastern Alps, where it likes to hide in shady areas and come out after rain.

Although common in some areas, it’s thought that they don’t tend to roam far in their lifetimes. Like all amphibians, they are highly sensitive to pollution and are threatened by rising temperatures and habitat loss.

This story was first published in the August 2022 issue of The Great Outdoors.