Oystercatchers are birds that make me think how brilliant it is that birds exist. Mostly, I find nature draws us in slowly – the smell of honeysuckle, the act of collecting shells – but other times it drags you from zero to awe immediately. Oystercatchers fall into the latter category. They are large, black and white wading birds with a spectacular orange beak and a shrill, persistent call. They are so thumpingly different from all other shore birds – and it’s this that makes me smile.

Main image: It’s hard not to smile at an oystercatcher’s vibrant break | Credit: John Williams

I think they must have been dreamt up one day, a pied masterpiece of make-believe. Wading birds are interested in terrain we’d likely avoid, preferring mud, sand and water, and they have the legs and feet to cope. Wet ground allows easy access to the delicious invertebrates that live there. For oystercatchers, this means worms in mud and shellfish on the shore. Their vivid beak is perfect for probing the earth and for getting into cockles and mussels.

In winter, look for them in fields around coastal areas. They remind me of a grazing herd of miniature Friesian cows, especially when their beaks are obscured by the long grass.

It’s not just their plumage that is remarkably different from other waders; they are the only British wading birds that bring food to their young. Most waders are ‘hatch and go’: within hours of leaving the egg, they’re on their feet and will start to forage for food, a magical reminder of inherited behaviour. This means nesting on the ground is non- negotiable.

Oystercatcher chicks, however, have the luxury of staying put, as their parents bring food to them. They generally nest on pebbly shores, by rivers and in fields, but can also find a home in human-made structures.

It’s for this reason I have grown close to one particular family. A short walk from my house is an old wooden pier. One of the large posts has rotted, top-down, to create a natural cup, and a pair have decided to lay their eggs in it.

This goblet of oystercatchers rises two metres from the sea and brings me joy and anxiety in equal amounts. One day – presumably when the tide is out – the chicks will be required to make the leap, and their fluffy, as-yet flightless, bodies will bounce on the pebbles below.

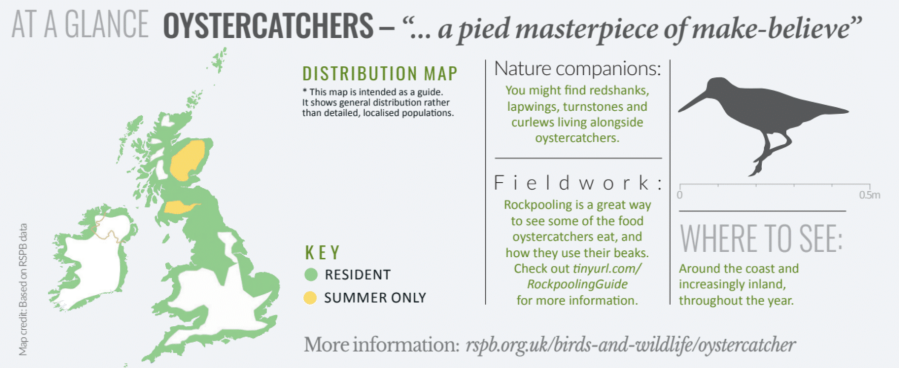

Oystercatchers are found throughout the UK, and although closely associated with the coast, they increasingly breed inland, especially in the north of England and in Scotland. They’re big and loud and long-lived; indeed, your local pair could live up to 30 years. They are increasingly recorded nesting on at roofs alongside gulls, so don’t forget to look up as well as down.