Deprivation and poverty are huge obstacles to getting outdoors. To make the outdoors truly inclusive, we need to put class in the picture, argues adventurer and author Phoebe Smith.

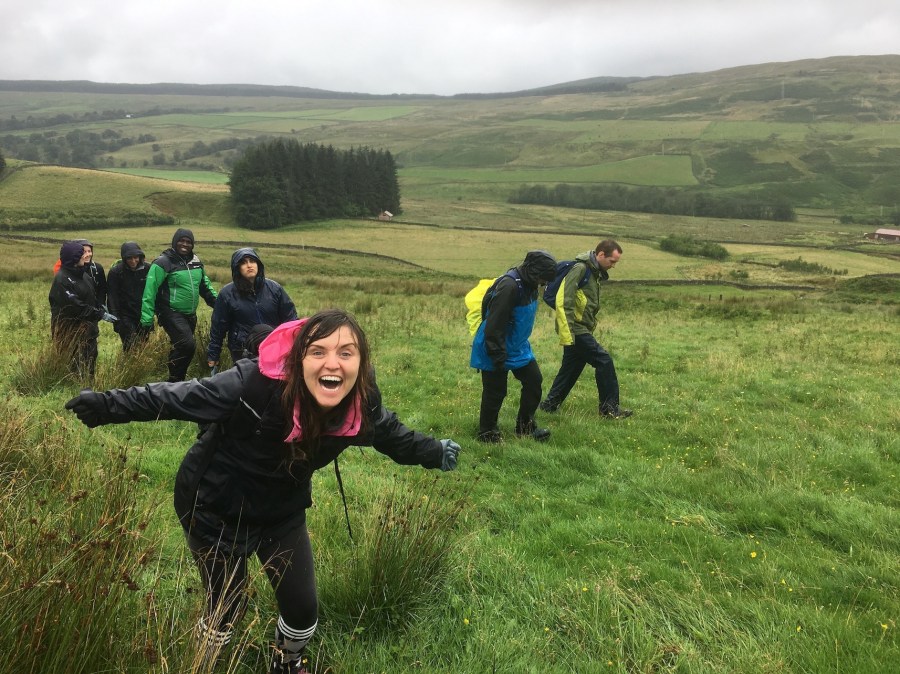

Main image: A group taking part in the Out There award, which is run by Ramblers Scotland to encourage people from all backgrounds to get outdoors.

My legs felt heavy. Not just tired from a walk, but physically heavy, owing to the fact that it was raining and I was wearing jeans – bootcut ones that were all the rage in the 90s and acted like portable ankle sponges, soaking up more water from the ground than was pelting down on me from the sky.

This happened many years ago, back when I was 17. Before then I’d never really ventured into the outdoors with the sole purpose of going on a walk – I wasn’t sure of the rules, where I could go and where I was allowed. But after meeting an outdoors-savvy drummer when joining a band, I’d been convinced to take the train to Betws-y-Coed to explore. Without knowing where to go I ended up walking in circles without so much as a waterproof and went home near-hypothermic, convinced that the outdoors wasn’t the place for me.

There’s an old adage that there’s no such thing as bad weather – only inappropriate clothing. But it’s easy to forget that when it comes to gear you need the right knowledge in the first place – and enough money to buy it.

Over the last year we have – rightly, and not a moment too soon – seen the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, which has also influenced the debate around access to the outdoors. What was once seen as something of a fringe concern became ‘mainstream’ at last, with Dwayne Fields on Countryfile highlighting the issue of the outdoors being seen as a ‘white’ environment. Equally, the murder of Sarah Everard had much of the press – including The Great Outdoors – highlighting the issues women face daily. But I feel that there is yet another important factor that is being overlooked that intersects with both of these: class.

Not a place for us

I grew up on the North Wales coast in an area affectionately nicknamed the ‘Costa del Dole’. Within 30 miles of my house was Snowdonia National Park; a 20 minute drive would have taken me to the Clwydian hills. Literally on the doorstep was the start of the Offa’s Dyke long-distance path. Yet the idea of heading out to explore any of these natural wonders never crossed my mind. And there are two key reasons why. First, none of my peers ever went, so I didn’t appreciate what was there for me to be able to explore. And even if I had, the second issue was cash – or rather lack of it.

Now that I can afford good outdoor gear I don’t flinch at the idea of getting caught in a downpour; I just grab my jacket and go out anyway knowing I’ll stay dry. But quality gear isn’t cheap – a half-decent waterproof is comparable in price to a month’s rent for many people. When I was struggling to find the money to pay that rent there was no way that I would sacrifice a roof over my head for an adjustable hood – no matter how good the hydrostatic head.

Then there is the issue of accessibility. If you haven’t got a car and bus routes are non-existent, then even a 20 minute drive renders a place out of reach. Parts of Britain are public transport ‘deserts’, and for those areas that do have transport links the cost of trains (even on short distances) are often the same price as a week’s shop.

Finally there is motivation – as activist Marian Wright Edelman famously said, ‘you can’t be what you can’t see’. If you are not fortunate enough to be brought up in an outdoorsy family or the culture or custom of the place you live holds that walking is something ‘other people do’, you feel intimidated by the thought of heading for the hills. And even today, with the proliferation of TV channels and online streaming options, programmes about adventure and exploration are still being commissioned which perpetuate the stereotype that the only people who can ‘survive’ outdoors have to be male, white, ex-military and upper class. Many of us who don’t fit that mould wrongly conclude that the outdoors is not a place for us.

Another group taking part in the Out There award, which aims to break down barriers to the outdoors for young adults from all backgrounds. Photo: Ramblers Scotland

Taboo subject

To talk about class is almost a taboo subject, despite the enormous amount of inequality in our society. Despite the UK being one of the world’s richest countries, around 4.3 million people are trapped in poverty. To put it in perspective that works out as nine pupils in every class of 30 officially classed as poor.

Looked at closely it becomes apparent that poverty is disproportionate across race and gender, with nearly half of those people coming from black and minority ethnic families, and a similar number from lone parent families – typically female-headed – who again struggle due to the disparity in pay between genders and the additional issues women face (according to a 2018 study 137,700 girls missed school due to period poverty, as they were unable to afford sanitary products).

Class has always been at the root of the struggle for outdoor access. Consider Benny Rothman, the leader of the famous mass trespass on Kinder Scout in 1932: a working class man who faced the rich landowner’s gamekeepers head-on – and subsequently went to jail along with five others – for the right of ordinary people and inner-city workers to access the countryside.

Yet even in 2021, the unspoken class struggle continues. During the pandemic, in cities such as London, people were regularly shamed for enjoying parks – the main way less affluent people, without gardens, could enjoy nature. Scenes of crowds and litter on beaches was blamed on the “geographically and culturally diverse cohort” by the Lulworth Estate in Dorset. Scouts – a key organisation for introducing kids from all backgrounds into the outdoors – has suffered from lack of fundraising due to COVID restrictions, threatening the closure of 500 troops, many within the most deprived areas. And a recent report from the University of Edinburgh and Ramblers Scotland found that the wealthiest fifth of adults in Scotland are three times more likely to hillwalk or ramble than the poorest fifth.

Dwayne Fields and Phoebe Smith, who have joined together to take underprivileged kids on an expedition to Antarctica. Photo: Phoebe Smith

Classism

Nearly 90 years on from Rothman’s act of walking rebellion I feel it’s time to call out this classism. We need to lobby for better access to the outdoors for disadvantaged young people and be able to provide better – and ideally free – public transport links to national parks and outdoors spaces. Outdoor education needs to form part of the school curriculum alongside the other so-called ‘key subjects’. We need to actively donate our old walking kit to organisations such as Gift Your Gear who ensure those who can’t afford it have no barrier to getting outside, and we need to add to the role models already in the media people who demonstrate that adventure and the outdoors is for everyone and not just the privileged few.

Because right now, there really is no such thing as inappropriate weather – but there are, it seems, inappropriate people.

Phoebe Smith is an adventurer, award-winning writer, broadcaster and photographer and co-founder of the #WeTwo Foundation which, in Feb 2022, will be taking a group of underprivileged young people from across Britain to Antarctica by expedition ship. To nominate a young person, or donate to the charity go to www.teamwetwo.com