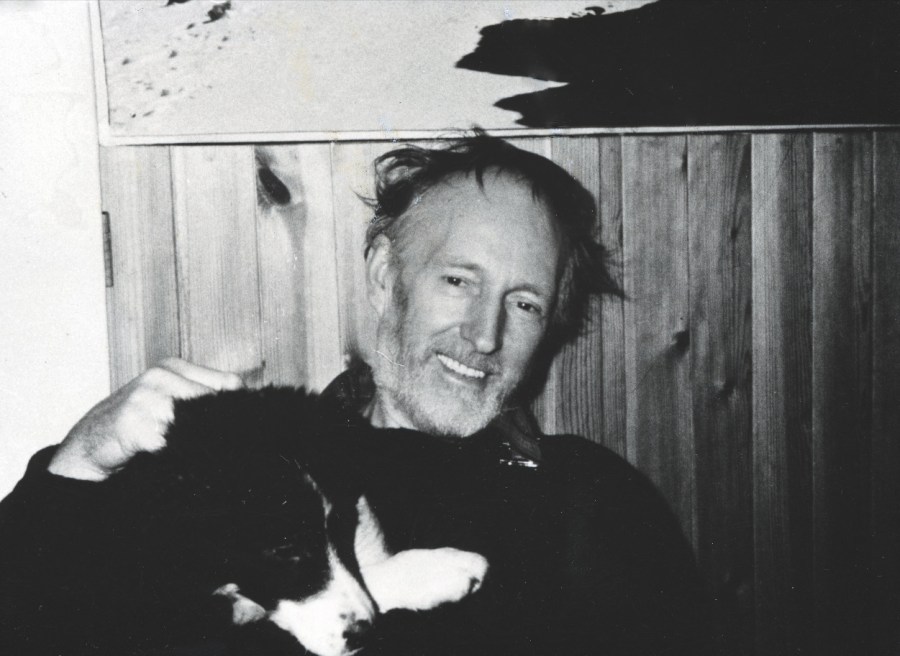

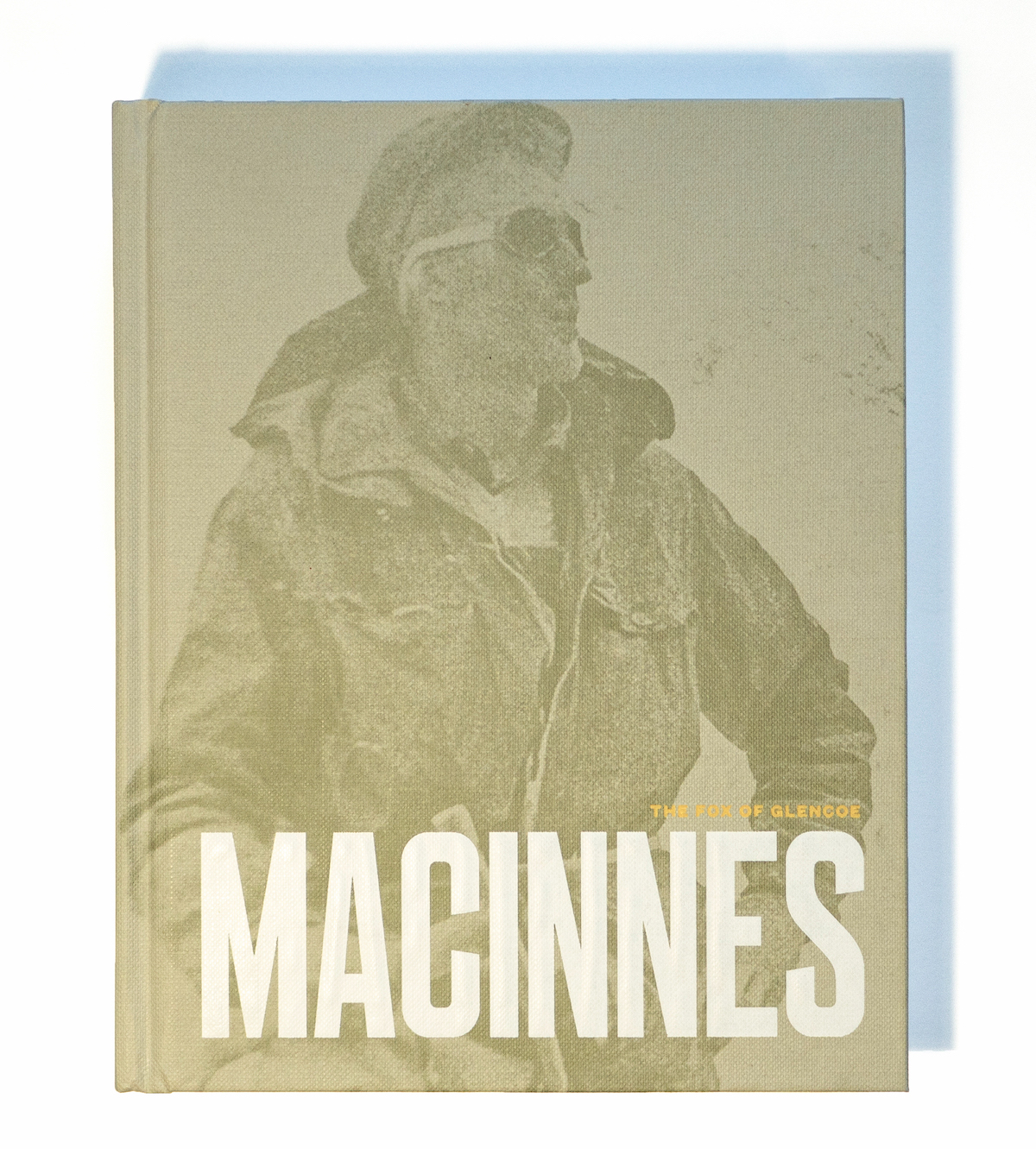

The Great Outdoors takes an exclusive look at a new collection of unseen and retold memoirs from Hamish MacInnes – legendary climber, safety adviser, equipment designer and fast car driver – The Fox of Glencoe

Hamish MacInnes was born in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland in 1930. A legend in the field of mountaineering, he pioneered many of Scotland’s most challenging climbs and numerous routes overseas. Tenacious and inventive by nature, Hamish dedicated much of his life to mountain safety and rescue. As well as founding both the Search and Rescue Dog Association and the Glencoe Mountain Rescue Team, Hamish’s revolutionary MacInnes Stretcher is still used worldwide, and his all-metal ice axe was a game-changer for modern alpinism. He was also a prolific author, publishing 26 books, including the seminal International Mountain Rescue Handbook (1972) and the classic Call Out (1973), in which he recalled his experiences with the Glencoe Mountain Rescue team.

Written and compiled before his death last year, The Fox of Glencoe chronicles Hamish’s adventures in his wry, elegant style, as well as including contributions from his close friends. It’s the definitive collection of stories from a mountain life lived to the full.

David Lintern caught up with Rob Lovell, publications manager with Scottish Mountaineering Press.

How did The Fox of Glencoe come about?

“I got an email out of the blue in December 2019, from the email address ‘notyet100’ and it read; ‘I have several hundred pages of a new book completed. Might you be interested? I’d like to see it published before I hit 100 years. Hamish MacInnes’. I was on expedition myself in the first part of 2020, as soon as I got back, I went to see him at his home in Glencoe.

“Hamish wasn’t terribly well in the last year of his life, he was 90 years old and battling illness, so progress on the project was sometimes interrupted – there was a good bit of back and forth, trying to get hold of material. About a month before he passed away things really started to gain pace, and with his passing we knew we needed to honour the task and the man and see the book through. From that point on it was a case of working with his executors – two mountaineering friends of his, Rob Taylor and Graeme Hunter – to find the remaining material and begin to piece the book together.

“Rob Taylor wrote to me about the role of the book in Hamish’s final years, after he came out of hospital having suffered with memory loss. ‘In 2014 Hamish got sick, and thereafter, as part of his slow recovery he got serious about wanting to get a final book out. There’s no question it played a huge part in his physical, spiritual, and psychological recovery. One must keep in mind that several NHS specialists were quite confident in stating that Hamish was on his way out and would never regain most or any of his capabilities. Yet again how wrong the experts were proven.’

“There had been a vast amount of work done on this manuscript before we saw it, both by Hamish and Rob, and of course with some of it appearing elsewhere before. There were also lots of new pieces. Our editor Deziree Wilson had the monumental task of consolidating and ordering the material, editing the stories themselves, and determining where the gaps were. We then spoke to Hamish’s friends to find the missing pieces.”

What about the pictures?

Getting the images ready was a massive job, trawling through what was a fraction of Hamish’s collection. Between Deziree and I we were able to select a set of images we thought would work in the book and then, using her intimate knowledge of the memoirs we were able to place the uncatalogued images alongside the text. Again, where there were gaps in the archive, we approached specific people to gather additional material. John Cleare’s images transformed chapters on the Eiger Sanction, Mountain Rescue and Hamish’s engineering, and Chris Bonington offered some of his beautiful photos from their climbing together. Both are incredibly evocative of the period. We were also provided with excellent photos by professional photographers, SMC member Dave Cuthbertson and Hamish Frost, who we’ve worked with on a few projects now.”

The print quality of The Fox of Glencoe is lovely…

“We took a decision early on that anything other than the best wouldn’t do for a book like this. We chose a UK printer – Kingsbury Press in Doncaster – who did a fantastic job and were a pleasure to work with.”

What happened once everything was in house?

“From September 2020, the project really got going with editing beginning in earnest. By February 2021 we had a good amount of written material and a selection of images, and we got our designer Gino involved. We received the final contribution from Walter Elliot (who sadly passed away in July) in April this year. There are many elements of the book that would have been simply impossible to complete without the help of Hamish’s friends. So, it was a very collaborative project, and we ended up with something that we hope is more than the sum of its parts.”

The Fox of Glencoe is a beautiful piece of work and very obviously a labour of love. What strikes you about it now, having seen it to fruition?

“I sat down with my young daughter when I received my advance copy from printers, and one of the things that hadn’t occurred to me until then, was that although Hamish had published in the past, here was the first book that brings together his whole life in one place. It portrays the character of the man, rather than just his achievements. It’s bookended with two fantastic photos – one of Hamish as a Toddler and another of him at 90 inspecting a modern MacInnes Stretcher – so it is a summing up, both of his own life and how he interacted with his friends and peers, as well as his contribution to mountaineering more generally. It obviously meant something to Hamish himself to go through that process.

“I don’t think I’d be speaking out of turn to say the whole team feels honoured to have worked on The Fox of Glencoe. Personally, when moved into publishing a few years ago, I never expected to be helping pull together something as special as this.

Buying direct from SMP directly supports outdoor recreation, is that right?

“Yes, we’re a subsidiary of the Scottish Mountaineering Trust, who provide grants to projects and organisations that promote public recreation, knowledge and safe enjoyment of the mountains of Scotland. All our directors are volunteers, and the publishing wing of the Trust supports its charitable objectives, so it’s all about celebrating and inspiring people to enjoy, appreciate and ultimately care for the Scottish mountains.

Hamish’s ‘tome’, as he called it, felt like a natural fit for our new, rebranded imprint and I was of course delighted when he got in touch with us. Perhaps we would say this, but it feels right that because we produce books borne out of experiences in the Scottish outdoors, any profit we make should be returned to supporting that same environment, and to the people who love it – sort of a virtuous circle.”

For more info or to purchase direct, visit https://scottishmountaineeringpress.com/

Here’s a short extract from The Fox of Glencoe, and a chapter entitled ‘Hobbling Around on the Eiger’, in which Hamish acts as safety adviser on the set of the Hollywood movie The Eiger Sanction while also suffering from gangrene.

We inched our way to the edge on our stomachs and peered over the vertiginous drop. The wall slipped away beneath us for around 2,500ft, so that we couldn’t see it for quite some distance until the overhanging rock eased to vertical and swept down a considerable distance before running out into meadows.

‘If we chuck the dummies off from here,’ I said to Dougal as I flicked down a small stone, ‘they won’t touch anything for about 3,000ft, and then only in passing until they reach the toenails of the mountain.’ We watched the stone get infinitely smaller until it disappeared.

‘The rock does seem solid enough,’ Dougal conceded, ‘but how do you propose Clint should fall when he cuts the rope?’

‘I’ll extend a ladder out from where we’re lying, like a diving board,’ I explained matter-of-factly, ‘so that the end is about 25ft clear of the face, and then erect another one from here so that the bottom of it rests on the diving board ladder. The top of the vertical one will be connected to the end of the horizontal one and it will also be guyed back to the ridge behind us. We’ll put in a couple of expansion bolts to hold the flank end of the diving board ladder in place on the rock face here behind us.’ I gestured to the flat rock surface behind where we lay. ‘It will work on the cantilever principle.’

‘It sounds crazy to me,’ he sighed, ‘but it’s your call. I agree, the place does seem OK.’

The contraption was ready by the next afternoon. When Clint and ace cameraman Mike Hoover landed, they looked somewhat alarmed when they saw the Heath Robinson-like structure we had cobbled together and realised they both had to perch on the very end of the horizontal ladder. Between them, they weighed not far off 400lbs, and as they moved out over the drop, the ladder bent like a cheap plastic ruler. The plot involved Clint hanging from the end of a rope that had snagged on the overhang above the Gallery Window. In the script, two ropes were thrown to Clint from the window by rescuers, and these were the ropes on which Dougal and I now belayed Clint. In place of the snagged rope, we had one that hung directly from the end of the ladder, and Clint would have to cut this as he hung from it, simulating freeing himself so that he could swing down onto the face. Dougal and I lowered Clint 30ft from the end of the ladder, and he tied on to the ‘snagged’ rope, which he was to cut as Mike lay spreadeagled above him on the end of the ladder with his heavy camera.

‘Are you tied on yet, Clint?’ I yelled.

‘Yeah, I’m on. Wait ‘till I get this knife out.’ He rummaged in his pocket for the Swiss Army Knife.

Most people in Clint’s position would have been spun out, but in his no-fuss way, he took it all in his stride like a true professional. It was highly risky for him to be holding a razor-sharp knife, especially once he had cut the rope, and he had to keep his cool and remember to drop it as soon as the rope parted. We also realised that the sudden departure of several hundred pounds of weight from the diving board would result in the ladder springing upwards. Mike steeled himself in anticipation.

After final safety checks and deep breaths all round, Clint yelled up, ‘Hey, guys, is this safe?’

‘It’s safe enough,’ I shouted, ‘but I wouldn’t do it.’

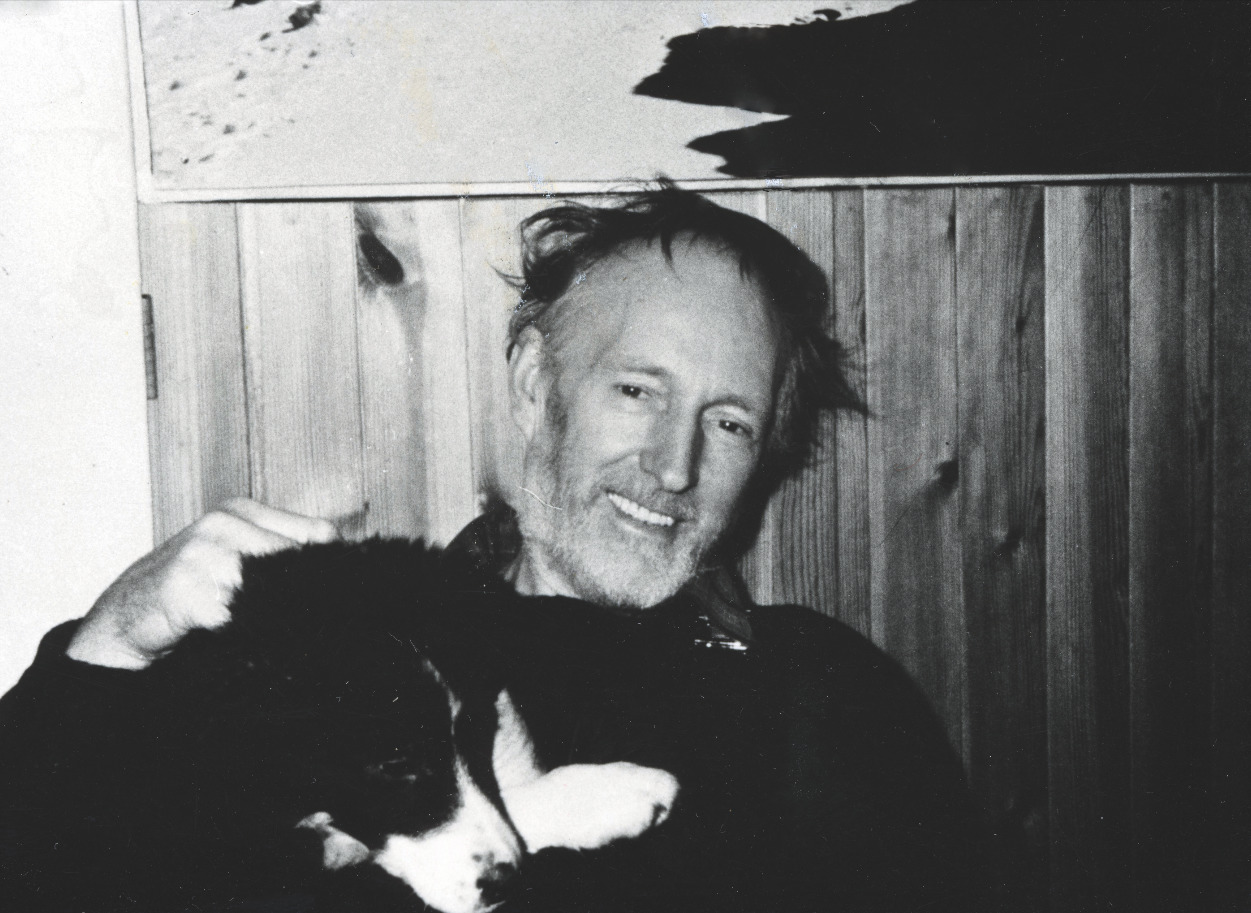

All images here courtesy of the MacInnes Archive