Andrew Wang’s earliest memories of the outdoors involve learning on the go. His parents emigrated to the UK from China a few years before he was born: “and for some reason,” he says, “my dad decided that walking was the thing they were going to do. The problem was, they really had no idea…” Most weekends, the family would pile into the car and drive from their home in Manchester to the Lake District, Peak District or North Wales.

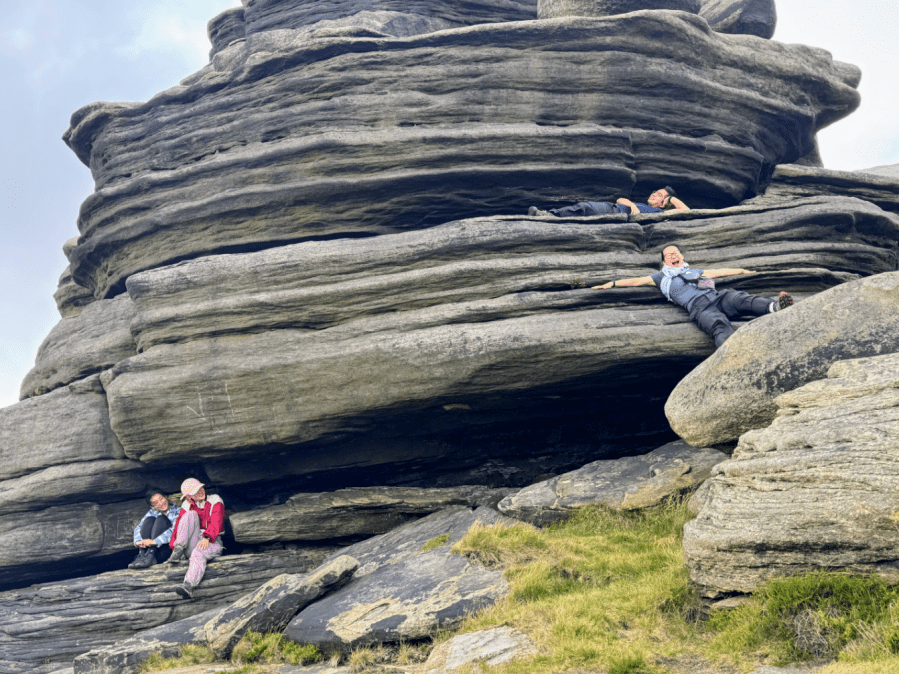

Main image: Playing in the Peak District | Credit: Samantha Smith

Part of the adventure, Andrew remembers, was figuring things out as they went along. “We had to learn it all for ourselves,” he says. “Like: why do you need waterproofs? Because once, we almost got hypothermia. Why do you need a tent without holes? Because we woke up one morning with red faces from the midges.” Navigation was a barrier for a while: “map reading was one of the things my parents had no idea about, and we would often find ourselves lost in a live quarry or in someone’s garden.”

He’s been a confident and experienced fell runner for years now – but it was only recently he began to really appreciate his early introduction to the outdoors, and to wonder why there were so few people in the hills who looked like him. “I think it must have been about five years ago that I was out running Froggatt Edge in the White Peak and I came across another Asian-looking guy. I was thinking, ‘wow, this is the first time I’ve ever seen an Asian guy out running on the edges’. And then I thought; ‘oh, maybe there are other people like me who exist in the outdoors’.”

At the time, Andrew was a member of All The Elements; a community championing outdoors access in the UK for underrepresented groups. “In that group there are outdoors diversity campaigners across a lot of different areas,” he explains. “Disability campaigners, people who lead groups for LGBTQ+ people in the outdoors…. We share a lot of similar issues, such as stereotyping and harassment. I was invited by the amazing Soraya Abdel-Hadi, founder of All The Elements, to join their retreat called The Summit. And that was really the catalyst for me to start ESEA Outdoors UK.”

ESEA (pronounced e-sea) stands for East and South East Asia; an acronym which campaigners would like to see more widely accepted in society. The group Andrew founded has united people with shared ESEA heritage who love being outdoors and want to fight racism by celebrating representation. It’s a grassroots organisation led by volunteers – Andrew says that this means everyone in the group feels passionately about its aims.

“I guess it started out as many of these community groups start – just wanting to find people who look like you. The root reason, though, is wanting to bring together a community that fosters belonging in nature, but is also trying to tackle bigger issues like racism in the outdoors.”

ESEA Outdoors runs events a few times per year, along with plenty of informal local meetups. As somebody who’s used to feeling like the odd one out in the outdoors, Andrew says that group meetups are incredible experiences. “We had one event last year funded by the Lake District Foundation. That brought 17 of us together – hillwalking, swimming and cooking ESEA food – which at the time was the biggest number of community members meeting in one place. There was a real empowerment in seeing what might well have been the biggest group of ESEA people taking up space and celebrating our identities in the Lake District.”

Another of his favourite memories from the group’s history involved an adoptee of ESEA heritage raised by a white family in the UK. “She joined one of our events, and she told our volunteer that she felt able to connect to a side of her identity that she had kind of put aside because of her love for the outdoors, and she felt understood when recounting stories of racism. She said that finding our community was the best day of her life.”

One way of viewing ESEA Outdoors – and the increasing numbers of grassroots organisations out there championing groups underrepresented in the outdoors – is as part of a broader fight for access to Britain’s countryside. We’re used to thinking of barriers to access as physical or legal (only 8% of land in England and Wales currently enjoys formal rights of access), but they can also be less tangible.

Andrew says that people from an immigrant background often feel acutely aware of these invisible barriers, which can range from perceived fears or not fitting in to the lack of an experienced support network. “On the flipside, though, it’s easy to be aware of your privileges. For example, I know that I’m an able-bodied man who can run fast. If someone harasses me, I can run away. But what if I was in a wheelchair? Then it’s a completely different story. Physical and intangible barriers to access can compound in different ways. Maybe you’re a queer working-class person, hesitantly figuring out how to go wild camping, but the impression you get is that spending a night under the stars is a paid-for commodity. That’s going to greatly affect your likelihood to get into nature.”

Educating ourselves about the challenges faced by marginalised groups is, he argues, crucial for breaking down barriers to access. Diversification also needs to be scaled up. Grassroots groups like ESEA Outdoors are an important part of the story, as is genuine representation – not superficial ‘inclusivity washing’ – from brands and the media. The more that people from under-represented backgrounds see others like them enjoying the outdoors and speaking out about their experience, the more they’ll feel empowered to get outside. And that’s not just good for the outdoors community; it’s good for nature as well.

“The aim for me of making the outdoors a more diverse place isn’t just to make people feel more welcome, it’s to foster a wider connection with nature,” Andrew explains. “I think it’s accepted now that in order to drive large-scale changes in the way we treat the environment, we need people to care about nature. But you won’t care about nature if you don’t feel welcome in it or if it’s not something which is easy for you to access.”

There’s still a long way to go before those barriers to outdoors access – so easy to overlook or misunderstand for those not directly impacted by them – are broken down. But Andrew observes that things are visibly changing. “I remember when I first founded ESEA Outdoors there were just two of us. On the first week we went for a walk over Bamford Moor, which was somewhere I went a lot as a kid. I remember seeing lots of East and Southeast Asian people walking around and thinking: ‘wow, this is completely different to what it was like 15 years ago when I was growing up’. It’s taken a lot of work to get here, but I feel like we’re reaching that first stage of people getting into the outdoors. The next exciting thing is how do we get them to feel a true sense of welcome and belonging. Because that’s how you develop a real relationship with nature and begin to use your agency to care for it.”

Read more about the ESEA Outdoors UK community at eseaoutdoors.uk and on Instagram @eseaoutdoorsuk.