I squatted next to Mohammad on the floor of his mountain hut, watching as this elderly shepherd etched lines with a stick into the ash covered concrete beneath. Rain hammered down on the tin roof while the room filled with smoke from the rickety wood burner beside us. Slowly, the lines took shape and formed a crude map of the region, centred around the Jordan River.

Main image: Finding flat and stone-free camping spots in the desert was often challenging | Credit: David Myers

He pointed to a place just west of the river and then tapped his chest. This simple gesture showed me where he was from. Now, I traced the outline of my intended route on the floor. My finger drew a line through Jordan, across into Israel and then through the West Bank. He looked at me wistfully. Despite the unhealthy amount of smoke stinging our eyes, I realised his tears were real. They told me everything that my limited Arabic could not – he longed for his homeland but could never go back.

Walking to learn

The first time I thought about a long-distance walk in the Holy Land, I was listening to a news report about the latest outbreak of violence in the region. It suddenly occurred to me how little I knew about such an important area. I wanted to see this place for myself, to view things outside the prism of extremist opinion and media bias.

A few months later I boarded a flight to Amman and did the only thing I know how to do when my curiosity gets the better of me – grab a backpack and get walking. The idea was to make a big loop on foot, traversing the Jordan River from source to sea on one side of the Jordan Valley, then returning to the source on the opposite side. After many nights pouring over maps and stitching together routes I had something resembling a plan. I was soon to learn that implementing a plan in this complicated and often volatile region was another thing all together.

I figured Jordan was a good place to begin before venturing into Israel and Palestine, offering a comparatively safe environment to remind myself how to desert hike. I spent two weeks traversing the country from North to South, being chased by rabid wild dogs, drinking tea over fires with shepherds and picking my way through wild sandstone canyons.

Although remote, Jordan’s desert teemed with life. Even in the most far-flung wadi one was never too far away from a rogue camel, the coffee sack structures of a nomadic Bedouin camp or the silhouette of a shepherd and the accompanying jangle of their flock on a distant ridgeline.

And so many of those I met in Jordan were the same as Mohammad – exiles from the troubles, refugees from their Palestinian homeland.

About 400 miles later I reached the shores of the Red Sea. It was time to cross the Jordan Valley and start heading back north for the remainder of the journey through Israel, Palestine and the Golan Heights.

The jocular Jordanian border guards, who took great delight in laughing at my passport photo already seemed like a distant memory as I faced the more mechanical interrogations by the Israeli border police.

After a nervous wait, I was finally waived through a labyrinth of corridors and out into the blinding sunlight. Later that day I came within a stone’s throw of the Israeli-Egyptian border. A sign warned that approaching or touching the fence endangered your life. I didn’t hang around to find out.

Stark contrasts

The contrast between the Israeli Negev desert and the Jordanian desert couldn’t have been starker. Here – just a few miles across the valley – was a landscape entirely devoid of people or any other signs of life. What was similar was the challenge of finding water.

On the Jordanian side, I had used a little broken Arabic alongside simple map pointing to ask shepherds about possible water sources up ahead. One involved me digging into a gravel stream bed. Another had me gagging as I filtered stinking water from an oasis that a myriad of camels, ibex and other desert wildlife also used to rehydrate.

In the Negrev there was no such advice on hand, so aside from little pools of rainwater my strategy involved walking long days in order to reach remote kibbutzim. These were strange self-contained compounds – islands of suburbia within a vast sea of desert.

The high perimeter fences and secured entrances gave a reminder of the political context into which these settlements were built. In between these islands, the remnants of Israel’s military presence littered vast stretches of otherwise empty desert.

I stumbled across unmanned military outposts, rusted tanks and barbed wire fences that stretched into the distance. Skirting a steep canyon wall one afternoon, I heard a loud, deep boom that had me dropping to the ground as rocks tumbled around me. Was it a rocket? A sonic boom from an unseen aircraft? I looked at my map and saw that the Negev Nuclear Research Centre was unnervingly close.

From here, I climbed down into the gigantic Makhtesh Ramon crater and emerged at the town of Mitzpe Ramon, where herds of ibex roam the streets.

Later, I arrived at a sheer cliff edge and stood in awe and confusion at a massive 1300-foot drop into a 4-mile-wide oval depression. This was unexpected – Makhtesh Katan translates as ‘small crater’!

My final days in the Israeli desert were spent descending to the Dead Sea, the lowest terrestrial point on earth. I wild camped on the cracked, lunar-like surface of the old sea floor, before scrambling back up to sea level and onto the ancient fortress of Masada.

Occupation

A few days before I was due to enter the West Bank, a group of international hikers were attacked by Israeli settlers in the area I was heading for. My cousin (based in Jerusalem) advised me to reroute on arrival, and so I detoured to Hebron. Poring over maps of the city, I tried to make sense of the tangled, fragmented mess of checkpoints, barriers, restricted areas and settlements.

Hebron is the only Palestinian city with Israeli settlers living in the centre. If anywhere will make you consider freedom of movement and how much we take for granted, it’s here. One day as I walked down a street chatting to a young Palestinian, we arrived at a checkpoint. He held back, before explaining that he was not allowed through. He would need to take a roundabout route avoiding the settlements and the many buffer roads around them.

The other side of the barrier was a no-man’s land, a desolate line of abandoned buildings stretching down what was once a busy market street.

At the far end lay a checkpoint, complete with turrets, barbed wire and loudspeakers that barked warnings if anyone hung around too long.

A street vendor took me up to the roof of his building to show me the extent of the settlements. Shortly after, a soldier popped out from a watchtower above and stared at us intently while talking into his radio. “I’ve seen people killed from that tower; we should get back inside,” the man said.

Later, as I walked through the old town I noticed a layer of netting had been erected above the street floor. A local explained that this was to an attempt to stop the daily barrage of rubbish thrown down onto the Palestinian market stalls from the settler occupied stories above.

Passing the Al-Aroub refugee camp presented a glimpse inside some of the most extreme living conditions in occupied Palestine. A labyrinth of narrow alleyways bisected a dense complex of overcrowded buildings where I saw children playing games using empty tear gas canisters.

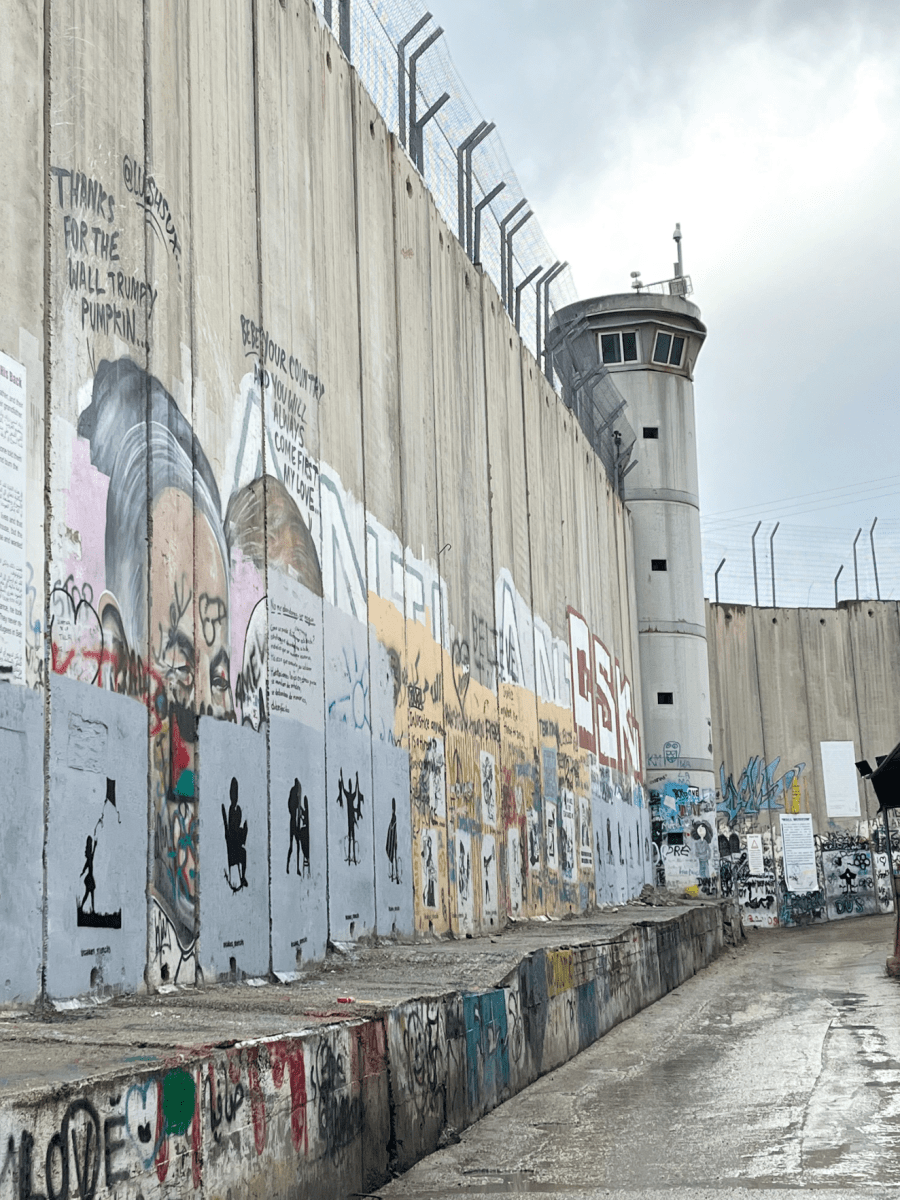

Further north I passed through the monstrous separation wall into Bethlehem via the notorious checkpoint 300, a bleak and dehumanising place made of metal and strip lights.

I emerged on the other side to a version of Bethlehem far away from quaint Christmas card nativity scenes. The reality here was a town overshadowed by a 9-metre-high concrete barrier and burnt-out watchtowers.

Intense relief

Finally arriving in Jerusalem seemed momentous. Every inch of the bustling streets seemed to exude a sense of intensity and significance. I spent many hours wandering the old town and soaking up the atmosphere, smells and sounds of the ancient city. From there, I continued north via the Palestinian capital Ramallah and the Christian town of Beirzeit before my plans were altered once again by the ever-changing political situation.

The reward for walking in the West Bank was experiencing a hidden side of Palestine, the beauty of the mountains, and the culture within. One evening I walked through a terraced valley filled with ancient, gnarled olive trees. I passed the silhouettes of people silently working the land as birdsong echoed around the valley.

This tiny parcel of land, and peace, cut off from its surroundings by a series of arbitrary barriers and fences, offered a moving, momentarily glimpse into the past and how things used to be.

Walking a tightrope

The Golan Heights formed a natural end point to my journey. After almost six weeks of walking, I was now back at the source of the Jordan River, near the snowy slopes of Mount Hermon. Traversing the infamous plateau felt like walking a tightrope between two worlds. To the East I could hear the shouts of villagers across the demilitarised zone in Syria. To the West the angular lines of a distant kibbitz perimeter fence, and far below, the Sea of Galilee.

The signs of Golan’s violent history were everywhere; a bombed-out mosque, destroyed Druze villages, bunkers leading to underground tunnels, tanks left in situ at the scene of their last battle and the constant warning signs of minefields.

On the last night of my walk, I met a young man wrestling with a tent. He was out enjoying a taste of independence for the first time, after being stationed on active military service near the West Bank. We talked long into the night. He was taken aback to hear about real people on the other side of the wall, and young men his age, separated by only a few miles, who in another life and circumstance could have been his friends. In the morning, we said our goodbyes and I watched as he disappeared down the hill towards Galilee, wondering what would become of him and his neighbours in the region.

As a foreigner I was in a very unusual position, able to transcend the boundaries and wander between the lines. It seemed absurd that none of the people I met on my journey shared this freedom. I encountered so many people who wished to meet their contemporaries on the other side, to talk to each other as human beings, away from the long shadows cast by their governments and leaders. But they were being kept apart, caught up in a self-perpetuating cycle, making it easier to commit monstrous acts of violence and with the possibility of dialogue and reconciliation ever more difficult.

A watershed walk

David’s route totalled approximately 1609km (1000 miles), with 31,000 metres (101,706 feet) of ascent, completed in 6 weeks. Due to ongoing military action in Gaza, it is not safe to replicate currently. The UK government advises against all but essential travel to Israel and the Golan Heights and against all travel to the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

To travel in Jordan, flights go direct from London to Amman. A visa is required, which can be obtained online. David often followed the Jordan Trail and Israel National Trail in these countries, with the Palestinian and Golan sections improvised.

Water caching in the deserts is usually advised but is expensive and logistically complicated. Very experienced walkers may be able to avoid caching, as David did. There are many minefields in the Golan heights, as well as a de-militarised zone. Visitors should stay away from these areas and stick to the trail.

This feature was first published in the October 2024 issue of The Great Outdoors.