Main image: Overlooking Llyn Llydaw in Eryri, a body of water brimming with mountain legends | Credit: Eilir Davies-Hughes

Stories are everywhere – they tell us who we are, how we got here, what we might be in the future. They are a navigational aid, just as a map and compass are. With well over 40 pages of stories in every issue, they are what The Great Outdoors is all about. This time, we’ve made it our task to look more closely at the tales from thin places that may help us navigate our present day, sweaty, heart thumping adventures. For the Celts, thin places were where this world and the next met, places with porous boundaries, portals to the unseen. Unsurprisingly, edges and horizons feature prominently – crags, cliffs, caves coves and coasts – and heave with bards and poets, fairies, trolls and phantoms, woe betides and moral lessons, the unexpected and the inexplicable.

We may like our mountain stories full of surprises – but that’s the last thing we want from our kit. In this special issue, we round up the best outdoor gear in our annual Gear of the Year Awards. Our gear testing team – the most experienced and diverse in Britain – have spent the past 365 using and abusing new kit from trusted brands. Here, we reveal the world-class kit they rate higher than the rest.

Highlights of this issue:

- Gear of the Year Awards 2025: we reveal the best bits of hill kit we’ve tested

- Hanna Lindon conducts a grand tour of Britain’s mythical mountains

- Emily Zobel Marshall knits past and present on an exploration of the Welsh 3000s

- David Lintern guides you to climbing Skye’s infamous Cuillin for mere mortals

- Mark Waring packrafts Swedish wilderness in Autumn on the Piteälven

- Nadia Shaikh gets a glimpse of the master of camouflage, the Ptarmigan

- We map beautiful bothy walks to nights out in wild, lonely shelters

PLUS: Jim Perrin paints a portrait of the Herefordshire Beacon and the Malvern Hills; Francesca Donovan guides you to walking the most underrated and undersubscribed national trail; Andrew Wang shares the story of ESEA (East & Southeast Asian) Outdoors; we share the latest news from the mountains; check the calendar of outdoor walking events we rate; and get inspired with our reviews of new outdoor books to inspire.

Read our October issue:

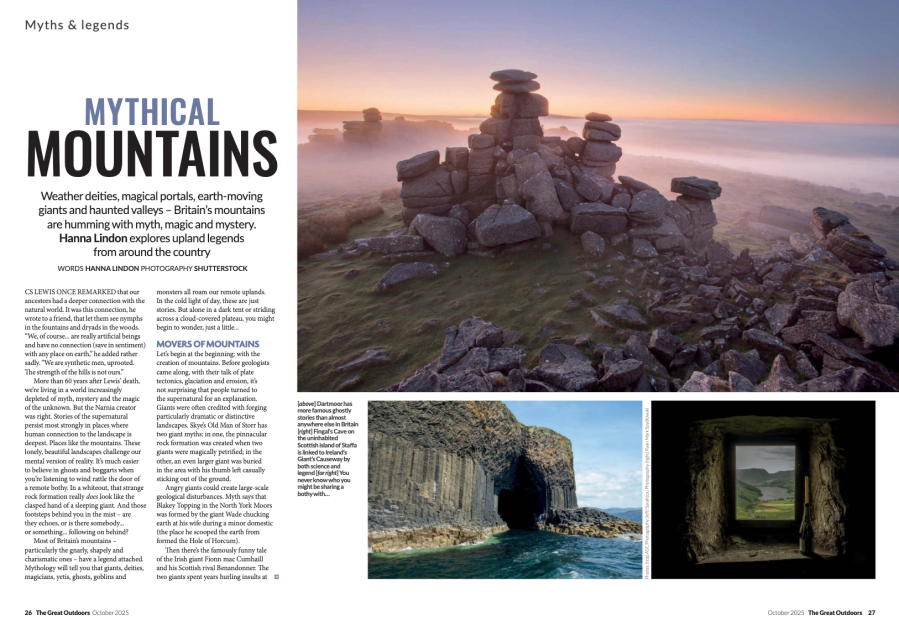

Mythical mountains: Weather deities, magical portals, earth-moving giants and haunted valleys – Britain’s mountains are humming with myth, magic and mystery. Hanna Lindon explores upland legends from around the country.

“Stories of the supernatural persist most strongly in places where human connection to the landscape is deepest. Places like the mountains. These lonely, beautiful landscapes challenge our mental version of reality. It’s much easier to believe in ghosts and boggarts when you’re listening to wind rattle the door of a remote bothy. In a whiteout, that strange rock formation really does look like the clasped hand of a sleeping giant. And those footsteps behind you in the mist – are they echoes, or is there somebody… or something… following on behind? Most of Britain’s mountains – particularly the gnarly, shapely and charismatic ones – have a legend attached. Mythology will tell you that giants, deities, magicians, yetis, ghosts, goblins and monsters all roam our remote uplands. In the cold light of day, these are just stories. But alone in a dark tent or striding across a cloud-covered plateau, you might begin to wonder, just a little…”

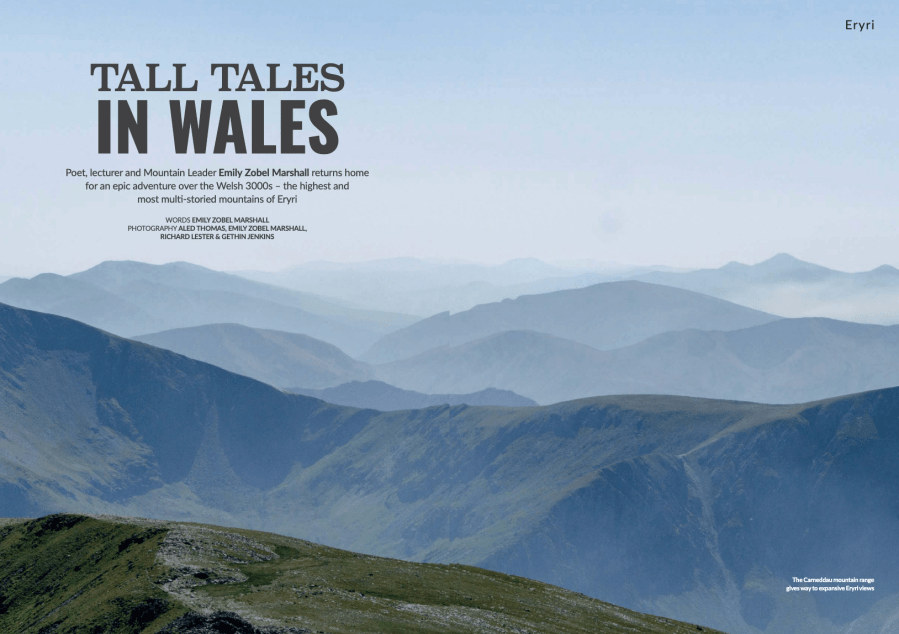

Tall Tales in Wales: Poet, lecturer and Mountain Leader Emily Zobel Marshall returns home for an epic adventure over the Welsh 3000’s – the highest and most multi-storied mountains of Eryri.

“I grew up in a remote farmhouse called Garth-y-Foel, near a tiny village named Croesor, nestled at the base of the peaked mountain Cnicht. Home was a kilometre from the road, unreachable by car. There was no TV and my brother and I lived a semi feral existence. Dad was English, mum Caribbean and our tiny primary school was Welsh speaking. There, tales from the Welsh legends Y Mabinogion, compiled in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries from Welsh oral traditions, were part of our daily diet of storytelling. At home, my mother told me Caribbean folktales about the wily spider trickster Anansi. I grew up in an enchanted place, still half haunted by the ghosts of druids, Roman soldiers, jilted lovers and magicians, a loaded landscape with a myth hitched to every rock, tree, cave and valley. In my teens, I made friends in Borth-y-Gest, a few miles away. Now, 30 years later and newly emboldened with a Mountain Leader qualification, I was returning to my Welsh homeland to make a new story. ‘The Borth Boys’ and I would try for the 15 Welsh mountains over 3000 foot, together!”

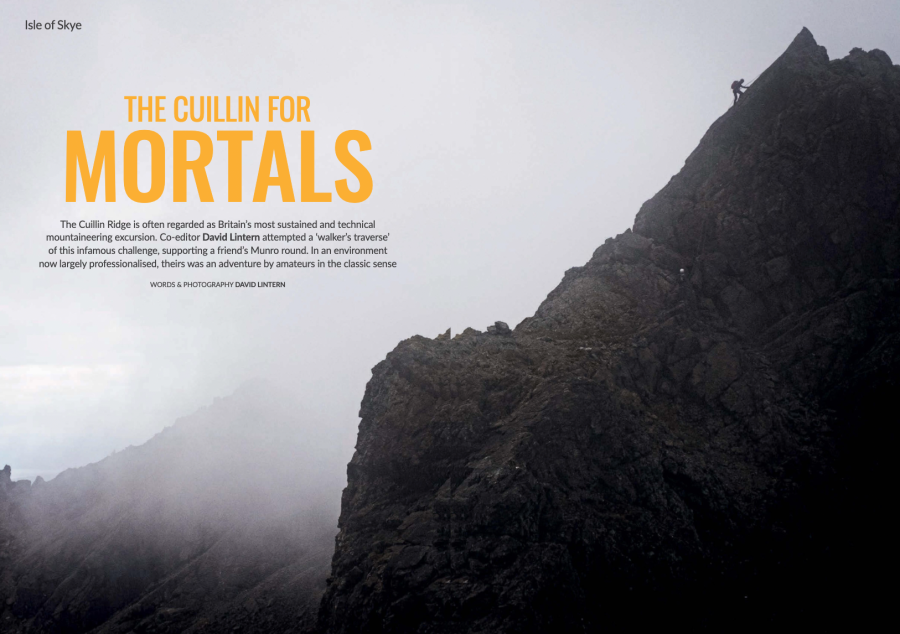

The Cuillin for Mortals: The Cuillin Ridge is often regarded as Britain’s most sustained and technical mountaineering excursion. Co-editor David Lintern attempted a ‘walker’s traverse’ of this infamous challenge, supporting a friend’s Munro round in the process. In an environment now largely professionalised, theirs was an adventure by amateurs in the classic sense.

“The Cuillin of Skye is made of dreams, perhaps a little of nightmares too, its jagged profile rising straight out of the sea or perhaps just straight out of Mordor. Certainly, it’s had this hold on my imagination since my first visit a quarter century ago. A friend and I were pretty literally washed down the Stone Chute by the most water I’d ever seen come from the sky. Back to the side of salmon and bottle of Talisker in our Broadford cottage, well and truly chastened. For mere mortals and aspirant Munroists, the ridge’s 12km of toothy scrambling and 11 Munros has a legendary reputation. The British Mountaineering Council reckon the traverse is one of the best mountaineering routes in Europe…”

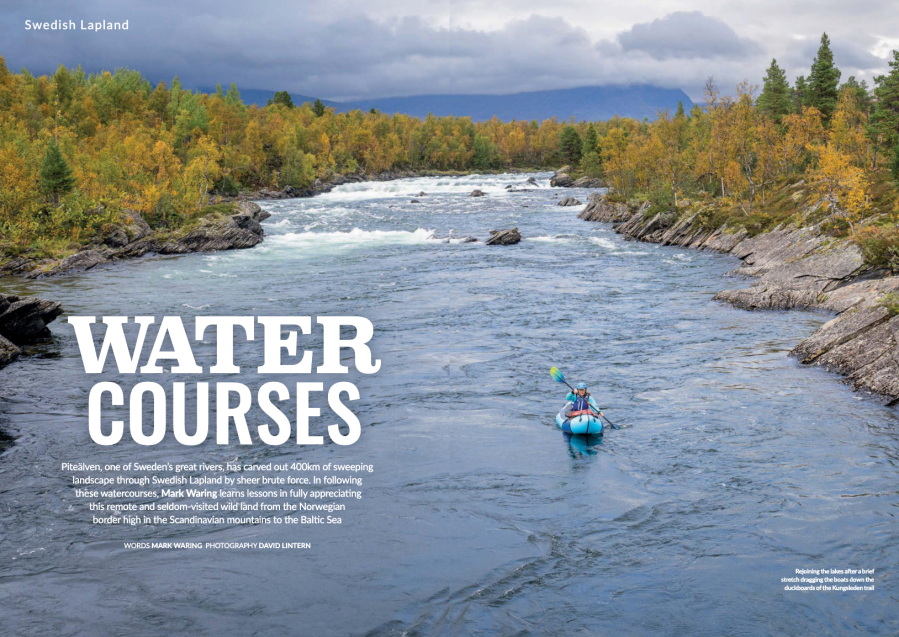

Water Courses: Piteälven, one of Sweden’s great rivers, has carved out 400km of mountain landscape through Swedish Lapland, shaping its geology through sheer brute force. By following these watercourses, Mark Waring learns lessons in fully appreciating this remote and seldom-visited wild land from the Norwegian border high in the Scandinavian mountains to the Baltic Sea.

“Packrafting offers so much. The sheer versatility of hiking with a small inflatable boat, ready to use in a few minutes, gives you unparalleled access to remote and seldom-visited wild land. There is an argument, too, that paddling a river system is the complete nature experience. Mountains and landscapes are shaped by water, their geology carved often by water’s sheer brute force. Only by following those watercourses can you fully appreciate them. Packrafting teaches humility, too. I am roundly taught that on the last day of this trip as I cockily assess the rapids before me as ‘straightforward.’ Blindly, committing my packraft to a whitewater run of several hundred metres, I am confident that I will effortlessly clear the half dozen foaming obstacles. Within a matter of seconds, misjudging the complexity of one of them, I am tossed into the river’s churning waters, at its mercy and helpless with several hundred metres of whitewater coming at me fast as I try to swim to the shore…”

Gear of the Year Awards 2025: All killer, no filler! Co-editor David Lintern introduces this year’s best of the best.

“Aren’t Awards a bit passé in 2025? Generally, outdoor kit is of excellent quality, more sustainable and affordable than it ever has been. How is it possible to pick out the best, when that depends so much on the individual and the use case? And who is to say, anyway? If we were to adopt an ‘everything and the kitchen sink’ approach, I’d tend to agree, but TGO’s Awards have always been about the best, not the rest. Deciding isn’t always easy, but that’s the job of an Awards process. OK, so we are changing tack a little this year, but not by much. The magazine has traditionally awarded only an overall Winner, plus a Highly Commended in each category. This time around we’re expanding that slightly, to reflect those changes we want to encourage around sustainability and affordability…”

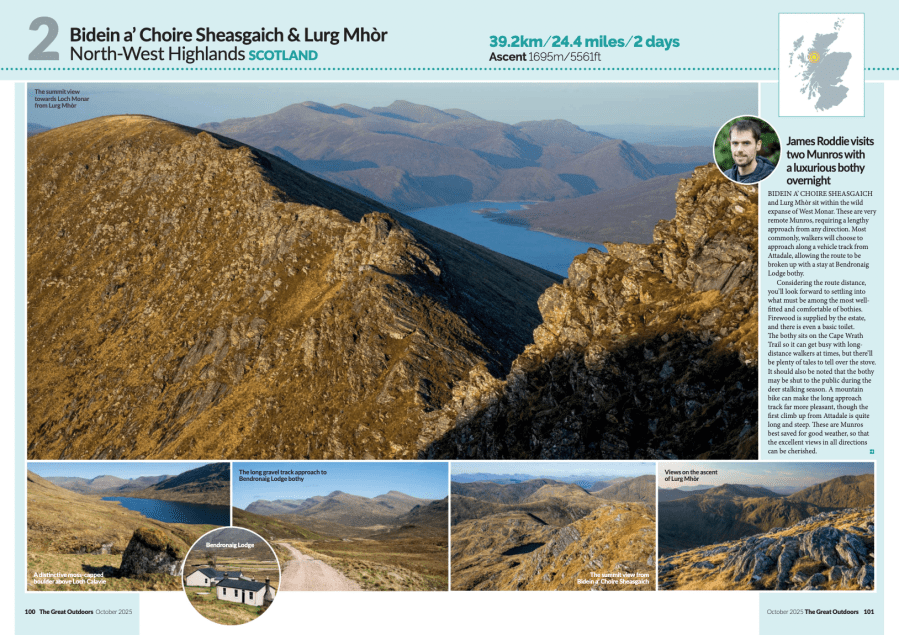

Wild Walks: Those of you who spend time in wild and lonely places may have stumbled upon small stone buildings, doors unlocked, standing sentry and waiting to welcome walkers who seek shelter. There are over 200 bothies maintained by those who volunteer for The Mountain Bothies Association (MBA). Here, our experts map diverse routes to seven of them to suit a day of adventure or a multi-day escape.

“A stunning Munro and an even more impressive Corbett sit side-by-side in the high, wild tract of land known as the Coulin forest, wedged in between wild Strathcarron and even-wilder Glen Torridon. Both of them thrust up into the Highland sky as improbable rocky crowns. An Ruadh-stac, in particular, looks nigh-on unassailable. But, if the soul of a mountaineer lurks inside you, assail it you must. The contrast between the two is an object-lesson in size not being everything. An Ruadh-Stac falls short of Munro status by twenty-two metres but is the finer sight, at least from this side. Maol Chean-Dearg throws its finest face northwards to Glen Torridon, but remains stupendous from any direction. These hills are a fine alternative when the spectacular peaks of Torridon itself are thronged. If the weather is clear, you’ll get staggering views northwards to Liathach, Beinn Alligin and Beinn Eighe with none of the queuing on every rock-step. Plus, to make life easier, you could sojourn at the Coire Fionnaraich bothy before, after, or even both if you fancy a shorter day.”