With the Lake District and Yorkshire Dales now in touching distance of each other there are new landscapes under National Park protection. Vivienne Crow took a look at some of the Cumbrian Dales that have now been annexed in an issue of The Great Outdoors earlier this year . Think you know Borrowdale, Wasdale and Langdale? Think again…

Borrowdale, Langdale and Wasdale. Three of the Lake District’s most popular valleys. Or are they? Things are not always what they seem in Cumbria… You may, for instance, think you know High Pike. But are you sure? Are you thinking of High Pike in the Northern Fells? Or High Pike to the north of Ambleside? And then there’s High Pike on Great Asby Scar and another one above Dentdale. Not to mention High Pike Hill in Mallerstang and High Pikehow on Haycock.

Originality isn’t a strong point when it comes to naming places in Cumbria. There are, for instance, three settlements called Carleton, three called Unthank and at least six called Newbiggin. (And I won’t dwell on the tautology that comes up time and time again – as in Torpenhow, for example. According to some interpretations, the name of this village in north Cumbria translates from Old English, Brythonic Celtic and Norse as ‘hill-hill-hill’.)

So, do you really know Borrowdale, Langdale and Wasdale? Unlike their namesakes, the Borrowdale, Langdale and Wasdale I refer to are among the least visited of Cumbrian dales. They lie in the east of the county: one just within the Lake District National Park; one awaiting news, as I write, of whether or not it will be allowed to join its illustrious neighbours to the west; and one being considered for inclusion in the Yorkshire Dales National Park.

Wasdale

The other Wasdale Head

To appreciate Westmorland’s Wasdale – meaning valley of water – let’s take to the skies and fly, crow-like, from the more famous Cumberland Wasdale.

From the green at Wasdale Head, in the shadow of Scafell Pike, set a course east, due east, and don’t waver from that line. Over the harsh, rocky scenery of Lingmell Crag, Great End and Allen Crag; above the high, open peatlands of Martcrag Moor and carefully negotiating the gap between Eagle Crag and Slapestone Edge; over the repeating ridges and valleys of the Fairfield and Kentmere ranges… Keep going, for nearly 37km, as the crags, the steep-sided dales, the excitement of the typical Lakeland landscape gives way to something more modest. And finally, you reach Wasdale Head… a sad, abandoned farmhouse surrounded by lonely moorland.

Ringing this forsaken valley is a group of small, grassy hills that make up a short, mostly pathless horseshoe: Whatshaw Common, Little Yarlside, Great Yarlside – the highest of the lot at 585m – and Wasdale Pike. There’s a tremendous sense of space and openness about these vast, rolling grasslands.

The abandoned farm buildings at Wasdale Head

This is sheep country: apart from these little white dots scattered about, as well as the walls and fences that dissect the landscape, it’s generally featureless terrain. A rocky outcrop on Great Yarlside provides a moment of excitement, but this isn’t a place you come for thrills; this is a place sought out for solitude, to escape from the Lake District crowds.

You come here to walk under big, endless skies, to listen to the skylarks, to watch the kestrels hovering over their prey. When I last visited, I stood close to the crumbling walls of the old farm and watched a solitary red deer stag grazing on the marshy ground in the valley bottom. He stood. I stood. For 20 minutes, not a movement. Then a quick shake of the head, probably midge-induced, before he returned to his meal.

Up on the tops, the peat was, in places, springy after a long spell of dry weather, but I remained vigilant: the cotton grass swaying in the breeze branded this as a land of bogs. My terrier Jess, going on ahead on a long lead near Wasdale Mouth, bobbed up and down on the marshy ground as if it were a trampoline. She weighs just 7kg. Doubting the ground’s ability to hold an additional 53kg – and that wasn’t counting my daysack – I went round another way.

Large, solitary boulders of pink granite provide a moment of geological interest on the grassy southern slopes of Wasdale Pike. Pink feldspar crystals give the rock its distinctive colour, making it a popular choice in the construction of monuments. The quarry, worked intermittently since the second half of the 19th Century, can be seen about a kilometre to the east. Its end product, polished up to look a pink, shiny treat, can be seen further afield: in the grand columns flanking the entrance to St Pancras Station in London, for example, and the pillars of St Mary’s Cathedral in Edinburgh.

Borrowdale

Borrow Beck flows through one of the loneliest of Cumbrian dales

Little more than 3km south of Wasdale on the A6 is Huck’s Bridge, spanning Borrow Beck. So this, then, is the ‘other’ Borrowdale, probably the best-known of the three ‘alternative’ Cumbrian valleys visited on these pages. It’s received some unwanted attention over the last few decades – when utility or energy providers have jealously eyed its wild setting, unprotected by National Park status, and drawn up plans that would change it forever.

Most recently, in 2005, the high ground between Borrowdale and a neighbouring valley, Bretherdale, was the scene of a fierce environmental dispute. Plans were put forward to build what, at the time, would have been England’s largest wind farm along the Whinash ridge – 27 turbines, each 115m tall. While environmental groups such as Friends of the Earth backed the proposals, local conservationists opposed the scheme and won the backing of celebrities such as Melvyn Bragg, Chris Bonington and the botanist David Bellamy. After a passionately argued public inquiry, the plans were rejected.

Looking back down the Breasthigh Road which links Borrowdale and Bretherdale

Borrowdale – meaning valley of the fort – is no stranger to ‘green’ controversy. In the early 1970s, after a failed attempt by the Manchester Corporation 10 years earlier to flood the valley and turn it into a reservoir, the Water Resources Board put forward an even more ambitious plan that included a reservoir, a new road and water sports facilities. Prominent campaigners against this proposal included Alfred Wainwright who, in his 1972 book Walks on the Howgill Fells, described Borrowdale as “the most beautiful valley in Westmorland outside the Lake District”.

In a scathing attack on the water authorities, which he described as “cannibalistic”, he wrote: “Must they devour and destroy for ever areas of natural beauty that have taken ages to fashion?” Walking through Borrowdale, Bretherdale and along part of the Whinash ridge last summer, I couldn’t help but wonder what this place would be like today if the ardent pleas of Bragg, Bonington, Wainwright et al hadn’t won the day. Climbing the rough track, known as Breasthigh Road, I looked down on the beauty and isolation of this valley, a far cry from its busy namesake near Keswick.

The fells are low by Cumbrian standards – never even managing the dizzy heights of 500m – but they have a rugged remoteness that makes them feel more substantial. A few tiny conifer plantations cling to Borrowdale’s steep, south-western slopes, while gentler, grassy fellsides rise to the north-east. Further down the valley, in the dale bottom, are indications of a more pastoral scene.

Here lie the ancient farmsteads and meadows belonging to Low and High Borrowdale. The latter was purchased by the Friends of the Lake District in 2005. Unlike in neighbouring Bretherdale – where farm machinery lies rusting in fields, the roofs of stone barns are long gone and drystone walls are topped with thick, spongy layers of moss – in Borrowdale, sheepfolds, walls and buildings have been restored.

Descending back into Borrowdale near the end of the walk

The conservation charity has also created upland hay meadows and planted woodland on the 44 hectares that it owns in an attempt to “restore the traditional character” of a Westmorland farmstead. The high ground on both sides is access land, providing walkers with a chance to stride out along lonely, grassy ridges: Ashstead Fell, Mabbin Crag, Castle Fell, Whinfell Beacon and Grayrigg Pike to the south; Whinash, Winterscleugh, Belt Howe and Jeffrey’s Mount to the north.

While three old routes climb the valley sides, linking Borrowdale with its neighbouring dales, another bridleway follows a beckside course from Huck’s Bridge almost all the way to Low Borrowbridge, the site of the Roman fort after which the valley is named. Here, with the roar of the M6 overhead, Borrow Beck enters the River Lune, and the old Westmorland gives way to the old Yorkshire, all now part of Cumbria. On the other side of the gorge – a key boundary and transport portal – are the steep slopes of the Howgill Fells. And penetrating deep into the heart of these hills that are not quite Pennine and not quite Lakeland is our third and final doppelgänger…

Langdale

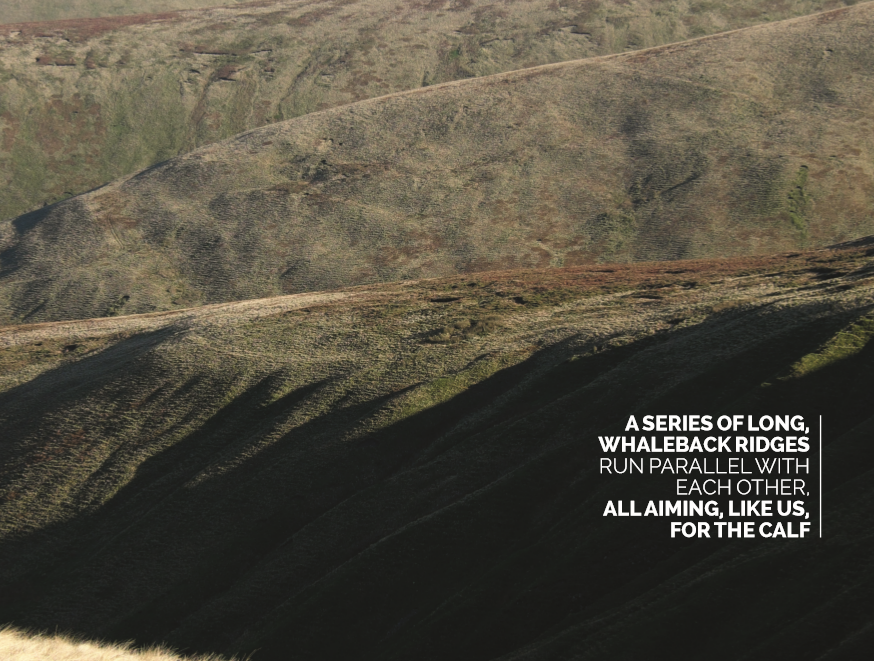

The Howgills’ long, parallel whaleback ridges

Langdale is, as its Norse name suggests, the longest of the northern valleys emanating from this dome-shaped massif. From the point at which it enters the Lune at Gaisgill, it can be followed upstream, through rough pastureland where hardy ewes graze and up between incredibly smooth, steep-sided hills to the point at which it splits into ‘grains’ originating from the grassy, northern flanks of The Calf – at 676m, the highest point in the Howgills.

With our sights set on a circuit of the hills surrounding the top end of Langdale – culminating, as almost all Howgill walks do, in a visit to the trig pillar on The Calf – Heleyne, Jess and I parked in Bowderdale and then crossed farmland and damp pasture to reach an old bridge that crosses Langdale Beck just above its confluence with Udale Beck. This old, stone construction, covered in grass and with no parapet to protect users from the churning waters below, is not marked on Ordnance Survey maps. Explorer maps suggest a ford slightly upstream of here, but I didn’t fancy taking our chances with that after recent heavy rain.

The climb on to our first top of the day, Middleton, was straightforward. All the while, off to the left and right, a series of long, whaleback ridges ran parallel with each other, all aiming, like us, for The Calf. Approaching the Howgills’ highest point from the north requires a relatively long walk-in, but once the climb up from the valley is over, the way ahead is unfettered: there are no walls or fences to impede, no crags to surmount and very little in the way of bog, peat hags or even heather to slow you down.

The broad ridges are simply attired, wearing little but grasses and soft mosses, allowing ground to be covered rapidly. Up and over Simon’s Seat, Bleagill Head, Stowgill Brow and Bush Howe. Occasional shafts of sunlight penetrated the sparse cloud cover, illuminating the valley sides, worn smooth by ancient ice and now looking almost silky in this soft, early winter light. I remembered a time, as a student in Sheffield, ‘sledging’ down grassy slopes with friends on the south-western edge of Kinder Scout, ripping holes in the orange survival bags that did little to protect our bums from the lumps and bumps encountered on our speedy downward trajectory.

The top of The Calf, the highest point on the Howgills Fells

The seemingly velvet slopes of Bush Howe and White Fell invited a similar style of descent – undoubtedly faster – but I’m older and, hopefully, wiser now…

Not having seen a single other walker since leaving Bowderdale, we were surprised to find a small group gathered around the trig pillar on The Calf: hillwalkers sharing their routes, their opinions on the weather, their experiences. As we parted company, each pair went off in a different direction. We headed north-east and then north, along the invigorating crest of Hazelgill Knott and West Fell, barely aware of gradually losing height.

As the sun sank low in the sky, the surrounding hilltops took on a slightly orange cast. Far to the west, the hazy outline of the Lake District’s high central fells formed a wistful horizon full of hillwalking potential. Below, the serpentine beck weaved sleepily through Langdale. Gazing down on it, I realised that, in my insatiable appetite for the high ground, I’d barely visited the valley that formed the basis for my walk. I noticed a faint trail along the base of the slope on the other side of the beck, leading up towards the remote, forgotten dalehead. Where the beck split in two, an inviting spur rose Calf-ward. Already, a return visit began to take shape in my mind.

Words and pictures: Vivienne Crow