Yosemite’s incredible mountain architecture inspired the modern conservation movement. At a time when America’s national parks are under threat, a visit to the valley proves an emotional experience for Daniel Neilson

This feature was first published in the December 2018 issue of The Great Outdoors.

By Daniel Neilson

The gears automatically shifted up as I sped along California Interstate Highway 140. I carefully swerved around the few trucks that were still trucking as the sun began to rise. On the radio – 96.9 The Eagle – the show was ‘Acoustic Tornado presented by Bob Weirmayer’. The singalong playlist perennials of The Doors, Rolling Stones, AC/DC and Tom Petty were turned down on this Sunday morning in favour of acoustic ballads. “On this Earth Day special,” Bob was saying gently and deeply, “It’s perhaps apt that we close the show with The Last Resort by The Eagles. It’s a song that warned of looking after our environment long before it was recognised, before it became something we need now.”

“Some rich man came and raped the land, nobody caught ’em/Put up a bunch of ugly boxes and, Jesus, people bought ’em / And they called it paradise, the place to be/ They watched the hazy sun sinking in the sea.”

I turned onto Highway 99, as straight as the early road builders could muster through their theodolites. A heat haze blurred the road ahead. But all along this 80-mile route, the foothills of the Sierra Nevada shifted into focus, and above them, the snow-capped mountains of my destination: Yosemite National Park.

Into Mariposa, a town that celebrates its 150-year-old Catholic church and where Marshall Long – a man whose local roots run deep – had just been re-elected as District 3 Supervisor. The town’s mining museum has the ‘largest nugget of gold found in the Gold Rush’; the 1854 courthouse, the first in California, is still in use (although the prison is not); and the Pony Espresso is the best place to get coffee for 40 miles.

I turned left at the town’s only crossroads and continued driving, higher and higher. The scrubby foothills began to rise around me, greener and pine-covered. Occasional flashes of silver granite dazzled me in the early evening sun, and I was relieved to arrive at the Yosemite Bug hostel, and ‘the best meals in the valley’. I nodded my agreement as I ate my flat-iron steak in the restaurant and leafed through the Bug’s entertainingly idiosyncratic guide to the area: “Here’s what you need to know to be smarter than the average bear feeder.”

Yosemite Valley is where the famous names such as El Capitan, Half Dome and Yosemite Falls put on their show. “Locals call it Disneyland, but one look at this natural cathedral of towering cliffs and thundering waterfalls and you’ll be ready to forgive the tour buses and traffic lines.”

Challenging times

Right now the USA’s National Parks are under tremendous pressures. The big hitters like Yosemite and Yellowstone, Great Smoky Mountains and Grand Canyon welcome millions of visitors every year. At Yosemite Valley in the high season, it can take hours to get into the Park, let alone find a parking space (although, as I later learned, it’s easy to find quiet in along the backpacking routes that wind through Yosemite’s 1,189 square miles). But the biggest immediate threat is the country’s current administration. Over the next few days, I spoke to rangers and representatives, business owners and visitors. Most were reluctant to give their views to a journalist on the record, but all expressed their fears for National Parks countrywide.

Despite cuts in the National Park Service budget, Yosemite is unlikely to suffer greatly; it’s too famous. By contrast, few outside the States had heard of Utah’s Bear Ears National Monument until campaigners, buoyed by outdoor brands such as Patagonia, The North Face and REI, spearheaded international condemnation of the planned reduction in the size of the protected area. It didn’t work: last year it was reduced by 85% to eliminate “harmful and unnecessary restrictions on hunting, ranching, and responsible economic development”, according to President Trump. Writing in The Great Outdoors (June 2018), Ian R. Mitchell concluded: “Whether we like it or not, in the USA and elsewhere, our wild outdoor places are becoming increasingly politicised, and we should be willing and prepared to give all support in publicity and other forms of action to lovers of the outdoors who have the misfortune to be residents of Trumpland.”

After breakfast of blueberry pancakes, iced water and coffee, I made the short drive to the park. It should take half an hour, but I stopped frequently to stare at the River Merced, which flows directly out of Yosemite Valley. I’ve never seen a river travel with such force and violence. It was Spring, and while the upper reaches of the High Sierra were still covered in snow, the meltwater was ferocious. It was for this reason that I would hike alongside the rivers and waterfalls. Yosemite was also relatively quiet. There were plenty of visitors, but numbers are far from overwhelming at this time of year.

Gradually the granite walls began to grow out of the pine-packed mountains, the early morning sunlight casting a yellow glow. Higher and higher they rose, their sheer light-grey faces streaked with water falling hundreds of feet to the valley floor. El Capitan appeared, then Half Dome, and I stopped and got out. Even writing this now, I can feel the emotion rising through me. At the time I welled up, and a tear ran down my face; I was overcome by the vastness, the beauty, the timeless steadfastness of the rock and the delicate fragility of its flora.

John Muir’s California

In the visitor centre at Yosemite is a bronze statue of one of the heroes of the US National Parks: naturalist, writer and wild land advocate John Muir. He was born in Dunbar, Scotland in 1838 and died 76 years later in Los Angeles. In those rich years, Muir influenced some of the greatest decisions aimed at conserving the most beautiful areas of the United States. In time, other countries including the UK followed suit.

A bronze sculpture of John Muir at the Yosemite National Park Visitor Center by Bridget Keimel

© Daniel Neilson

Muir had emigrated from Scotland to Wisconsin as a child in 1849. When he was 28, and working at a in Indianapolis, he suffered an accident that nearly blinded him. After six weeks in darkness recovering his sight, he decided that his future lay in nature. He walked 1,000 miles from Kentucky to Florida, finding the “wildest, leafiest, and least trodden way I could” and later settled in San Francisco.

It was from this city that John Muir took his first excursion to Yosemite. Like me, he was overwhelmed by the landscape, “scrambling down cliff faces to get a closer look at the waterfalls, whooping and howling at the vistas, jumping tirelessly from flower to flower.” Settling in the area, he got work as a shepherd and eventually built a small cabin here, and spent his days heading deeper and deeper into the High Sierra, recording what he saw, philosophising and theorising. He also began to write for newspapers, advocating the preservation of America’s wild land.

Although he went on to live and travel elsewhere, Yosemite always occupied a place deep in Muir’s heart, and he campaigned passionately for its protection. In 1890 his dream moved towards reality with the creation of Yosemite National Park to protect the huge meadows around the Valley. But the most famous moment came in 1903 when Muir took President Theodore Roosevelt on an overnight camping trip in the Valley. After talking long into the night, the pair slept out at Glacier Point. Roosevelt famously remarked: “Lying out at night under those giant Sequoias was like lying in a temple grander than any human architect could by any possibility build.” The Yosemite Valley was later incorporated into the National Park.

Muir’s views were not without controversy, particularly when it came to indigenous populations. Although he appreciated how closely native people lived with nature and expressed sympathy for the crop-growing Ahwahneechee who had been driven from Yosemite onto reservations, Muir nevertheless argued that all human residents – natives and white settlers alike – should be removed from the National Park to prevent environmental damage, especially from sheep and logging. (His views later changed after visiting Alaska and seeing how the native Americans could live and work harmoniously with nature.)

Still today, people debate what makes a National Park. Is it ‘wild’ and ‘unspoilt’ that should be maintained, at the expense of people living there? What is a ‘wilderness’? How should it be managed?

Yosemite Falls

From the Yosemite visitor centre, with its museums and shops, offices and campgrounds, I walked to Camp 4, the famous location of the big wall climbing antics in the 1970s and 1980s, to climb to the top of Yosemite Falls.

This is one of the oldest historic trails in the park, dating back to the 1870s, and one no doubt John Muir would have been familiar with. Visitors had already thinned out, and in the strong spring sun I found myself walking largely alone. Hot switchback after switchback climbed 300m over a mile to Columbia Rock at 1,500m. Here, a few more walkers braving the heat stood at one of Yosemite Valley’s finest viewpoints. Ahead, Half Dome and Sentinel Rock framed the valley below. The light grey, silvery rock contrasted with the deep green trees: California black oak, ponderosa pine, incense cedar and white fir. It was views like this, photographed by Carleton Watkins in 1861, that inspired the House of Representatives, none of whom had been to Yosemite Valley, to set aside a ‘wild land’ ‘for everyone, and for all time’. The legislation was signed by President Abraham Lincoln in 1864, in the middle of the Civil War. It was the first time in human history that land had been designated in this way, for preservation and recreation, and set in motion the journey towards National Park status aided by John Muir.

Walking in Yosemite

- When to go: Summer and autumn are the best options for backpacking. Winter snows can lie until June.

- Trails: Ask a ranger for the quietest and best options for day trails. Yosemite Valley is unmissable, but you’ll find more solitude elsewhere in the park.

- Permits: These are required for overnight stays in the Yosemite Wilderness (one per trip). They are free, but limited in number. It is worth reserving them ($5 per reservation plus $5 per person) although there are always first come, first served permits, if you can be flexible in trail choice. Reservations are essential for accommodation in the Yosemite Valley. See nps.gov/yose/index.htm for full information.

- Safety: Federal regulations require the proper use of bear-resistant food containers.

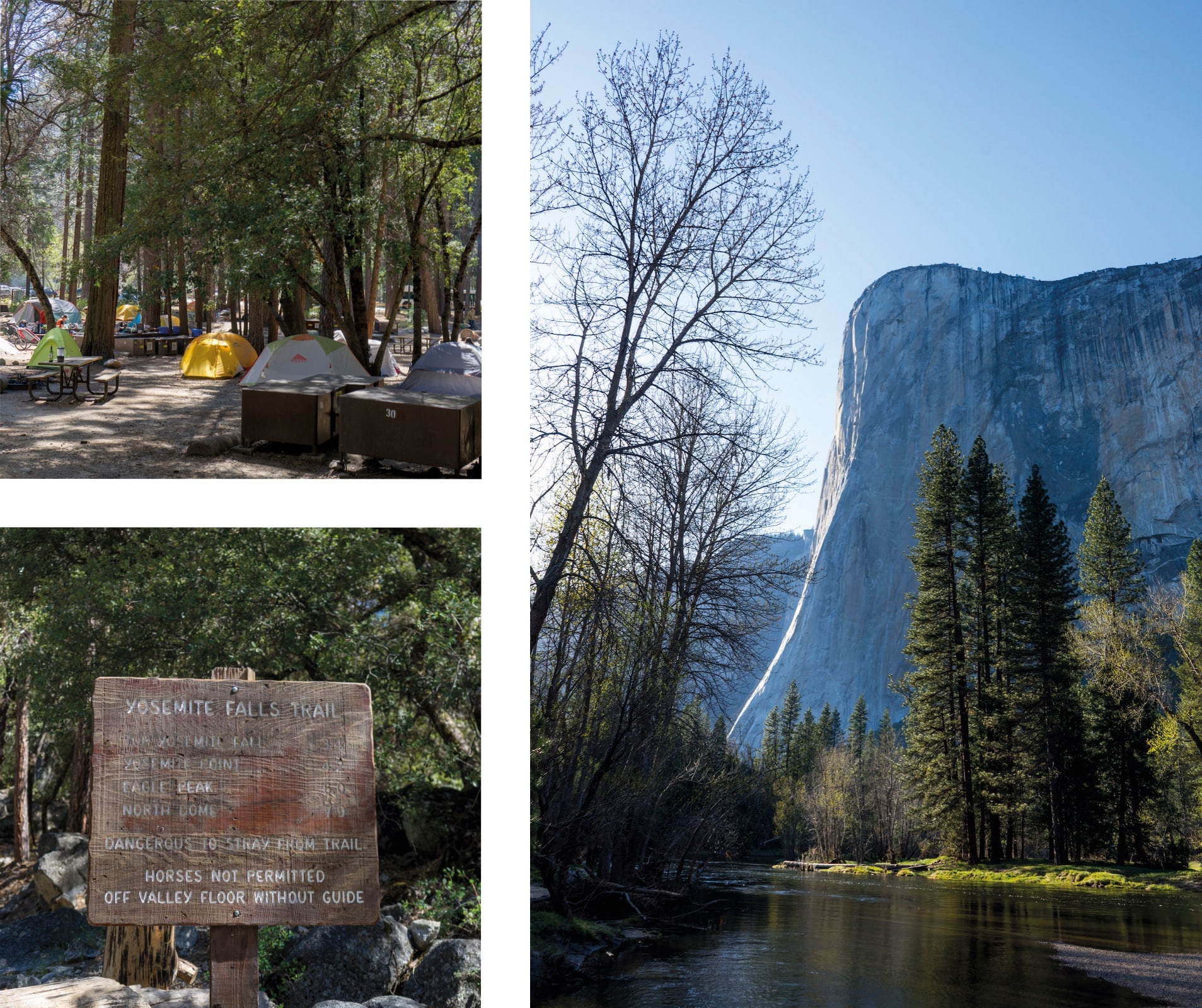

Left top and bottom: the Yosemite Falls Trailhead begins at Camp 4, made famous by big-wall climbers.

Right: El Capitan in the evening light: at least two teams were on the cliff when this photo was taken.

© Daniel Neilson

The trail curved around the steep mountain, a vertical cliff of granite rising above me. The sun was mercifully blocked, and a fine mist cooled me from the raging Upper Yosemite Falls, North America’s highest waterfall. The flora changed subtly too, the trees bigger, the leaves larger. Higher and higher, switchback after switchback I climbed. The trail eventually flattened off along a smooth granite path and twisted back towards the creek above the falls. John Muir wrote: “The rivers flow not past, but through us. Thrilling, tingling, vibrating every fiber and cell of the substance of our bodies, making them glide and sing.”

I sat awhile at the top, eating my sandwich and not knowing which way to look, what to think. The force of the water below me was too vast to comprehend. My head was swirling with the views. I snapped away with my camera, knowing that I could never relive this moment, high above the waterfalls, looking out over a view that had inspired such an important part of modern conservation. John Muir had years to digest this experience, the valley, the life among it. It never stopped stirring the man. He recognised it was bigger than him. I turned around and walked down the way I came, the sun already dipping behind the steep-sided valley.

“In every country the mountains are fountains, not only of rivers but of men. Therefore we are all born mountaineers, the offspring of rock and sunshine.”

—John Muir, Summering in the Sierra

I spent the next few days in a continuing state of awe and dizzying incomprehension. Like the Grand Canyon, and like the Giant Sequoia that grow here in the High Sierra, it can be hard to take in.

Nicknamed simply ‘Big Tree’ by John Muir, the Giant Sequoia or Sierra Redwood appears nowhere else in the world – only in California’s Sierra Nevada, in 68 scattered groves. Outside the Yosemite Museum is a section of a tree that fell in Mariposa Grove in 1919. It measures almost ten feet across.

Someone had thoughtfully placed signs along the rings of the trunk, marking a timeline of historical events. On the outermost rings of the tree are engraved metal signs: ‘1890 Yosemite National Park’, ‘1864 Lincoln Signed Yosemite Grant’, ‘1860 Civil War’. About halfway to the centre, it read: ‘1492 Landing of Columbus’. Towards the centre: ‘1066 Battle of Hastings’ and somewhere near the middle, when the Big Tree was a mere sapling: ‘AD 923’.

That’s a life of over a thousand years. The challenge we now face is how to protect Yosemite and its like for the next thousand years.