If you like your walks quiet, your views wide, your air clean and your wildlife abundant, then Northumberland is the place to go, says Vivienne Crow

In the May 2018 issue of The Great Outdoors, available now, Vivienne Crow introduces the delights of walking in Northumberland. You can read the full feature in our print issue, but here we’ve published two more walks for you to enjoy.

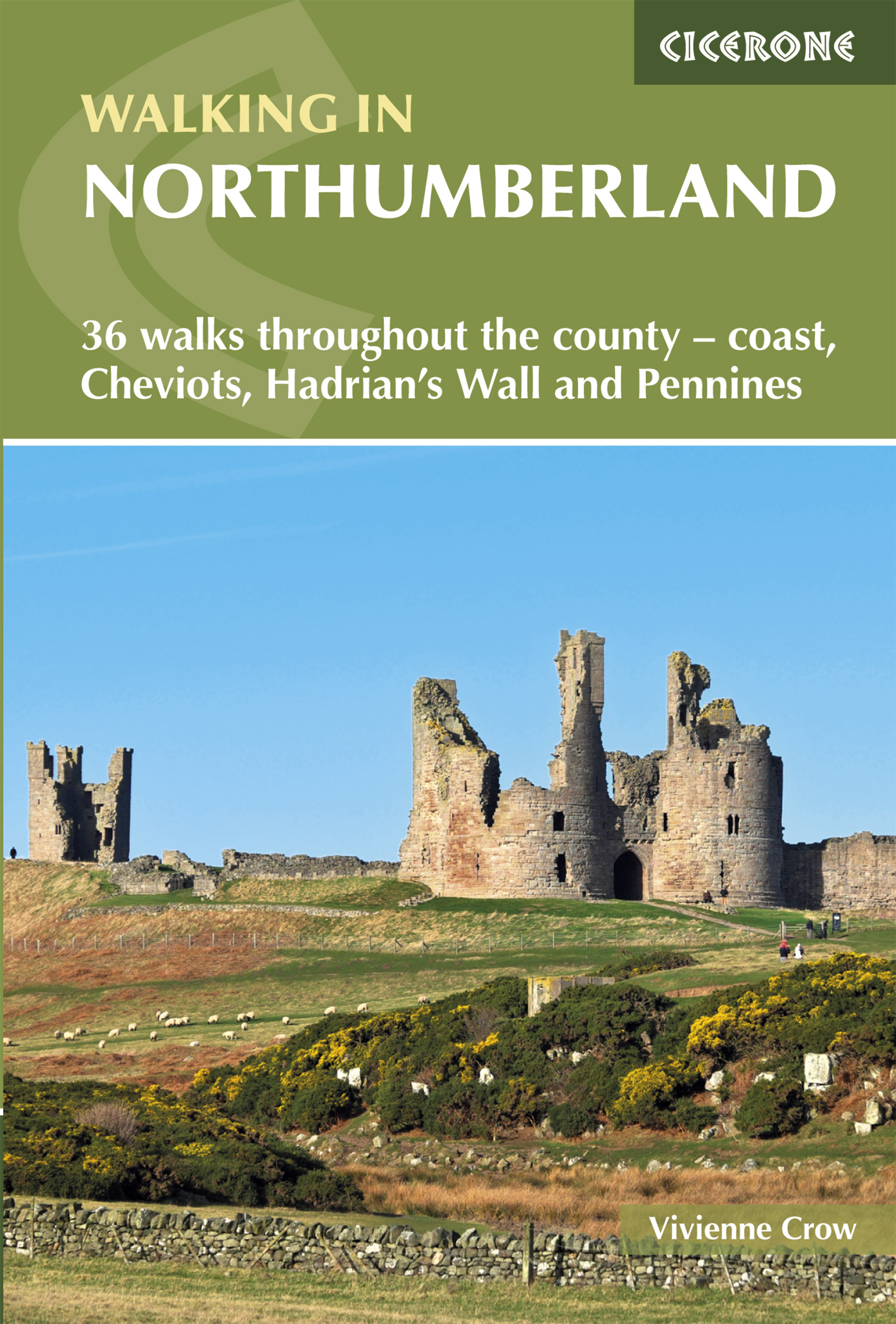

Vivienne Crow is the author of Walking in Northumberland, a new Cicerone guidebook to the county, priced £12.95. TGO readers can save 25% on a print copy by entering the voucher code TGONORTH at the checkout (valid until end of July 2018).

Stretching from Haltwhistle in the southwest to Berwick-upon-Tweed in the northeast – two places that, even as the crow flies, are about 95km apart – Northumberland covers more than 5,000 square kilometres. There are wide, open spaces here like no others found south of the border. This is England’s most sparsely populated county – with just 62 people per square kilometre.

Walking in Northumberland by Viviennne Crow. Save 25% by entering TGONORTH at checkout.

It’s a land that offers walkers everything they desire: the chance to hike for miles on end without seeing a single other human being; big skies, free from pollution and largely unfettered by man-made constructions; dramatic scenery; a wealth of wildlife; and a sense of history that means every time you lace up your boots and step out, you’ll be brushing shoulders with our ancestors.

Needless to say, over such a vast area, there’s a huge variety of landscape types. Roughly 25 per cent of the county, including Hadrian’s Wall and the high, rolling Cheviot Hills, is protected within the boundaries of the Northumberland National Park. The county also has two designated Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty – the Northumberland Coast, characterised by long, sandy beaches, dune systems and mudflats; and the North Pennines, which includes the spacious heather moorland of Allendale, Hexhamshire and Blanchland.

Outwith the protected areas, you’ll find the sprawling Kielder forests; the gorges and gills of the South Tyne Valley; great walks in the Rothbury area; and, between the sea and the Cheviot Hills, areas of low moorland where many of the county’s enigmatic cup-and-ring-marked rocks can be found as well as some of its sandstone climbing crags.

There’s a lot to see – if you’re a Northumberland novice and you fancy exploring the county, take your time and don’t bite off more than you can chew. Wooler and Rothbury make excellent bases for exploring both the Cheviot Hills and the coast. For Hadrian’s Wall, head for Haltwhistle or Hexham, both of which are also well-placed for the North Pennines.

The walks

Walk 1: Allenmill Flues

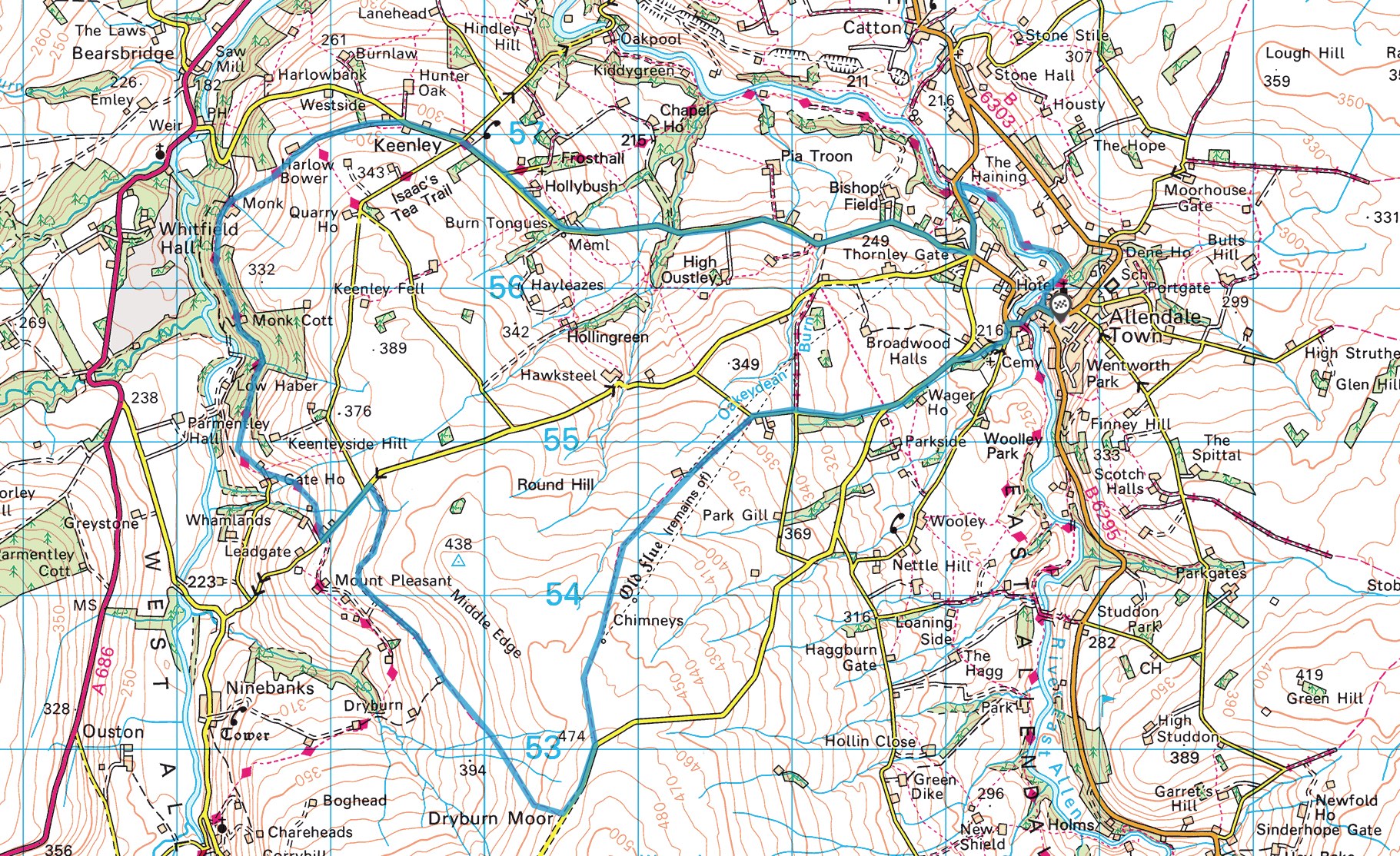

Start/finish: Main square in Allendale Town (GR: NY837558)

Distance: 11.6 miles/18.7km

Ascent: 1,690ft/515m

Time: 5-5½hours

Map: Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 Explorer sheet OL43 (Hadrian’s Wall)

Public Transport: Bus 688 (Traveline 0871 200 2233)

Walking in Allendale in Northumberland’s North Pennines inevitably involves encounters with the area’s lead mining past. It might be in the form of one of the old routes used to haul this valuable commodity across the lonely moors, or it might simply be an entrance to one of the long-abandoned levels. On Dryburn Moor above Allendale Town, the very tangible remains of the smelting process have become an integral part of the local landscape as I discovered while exploring the area with my partner.

Two long flues from the valley furnaces, where lead was extracted from its ore, became visible as soon as we left the lane near Frolar Meadows – two grassed-over, linear mounds, one clearly leading up to a tall chimney on the moorland skyline. As we left the enclosures behind, the crumbling stonework of the flues became more apparent. In places the arched walls had collapsed, allowing tentative glimpses into the long tunnel formed by the western flue.

During the nineteenth century, when Allendale was one of the most productive lead mining sites in the North Pennines, these flues played an important role in the smelting process. The furnaces were located beside the River East Allen; the flues condensed their poisonous fumes, carrying them for 4km up on to the open moorland, releasing what was left via vertical chimneys.

Allendale’s smelting mill flues led up to two vertical chimneys high on the moorland. © Vivienne Crow

As we followed the line of the western flue up on to the moorland, we bumped into a local dog walker. He was keen to share his knowledge of the industry. “Every now and then, the smelters would stand idle while they sent boys into the flues to scrape metal off the inside walls. Can you believe it? Those lads didn’t stand a chance – the flues were so toxic. But it wasn’t just lead deposits that the mining companies were after; they’d find silver in the flues too.”

On a sunny September’s day in the 21st century, it was hard to visualise the scale of the industry or to imagine the noxious environment in which local people had to live and work. The only sound was of distant sheep bleating; the early autumn air was crystal clear, the views northeast encompassing the Simonside Hills 50kms away.

Beyond the two chimneys on the highest part of the moor we began dropping into West Allendale, picking up the route of Isaac’s Tea Trail. This 58km circular walk celebrates the life of a former lead miner called Isaac Holden. Inspired by his conversion to Methodism in the 1830s, he became an itinerant tea-seller to help raise money for the poor and needy of the Pennines. Another reminder that these now-tranquil dales, with their sturdy cottages and neat lanes, weren’t always such idyllic places in which to live.

Crossing into East Allendale again, we passed the bottom end of one of the flues we’d seen earlier, now an interesting feature in someone’s garden, as well as the site of the smelting mill, now a commercial complex. As ever, life was moving on…

Walk 2: Yeavering Bell

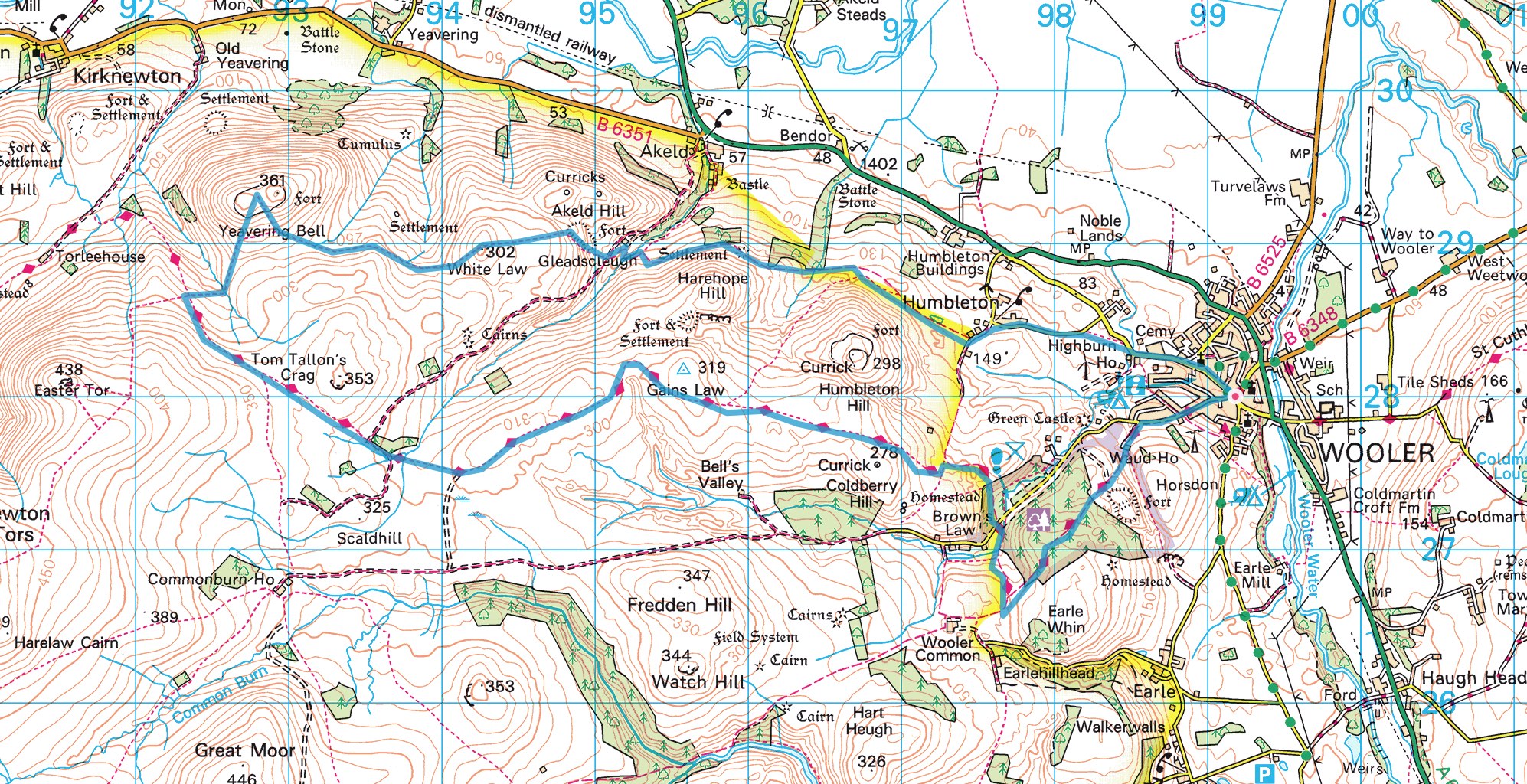

Start/finish: Free car park at Padgepool Place, Burnhouse Road, Wooler (GR: NT989281)

Distance: 10.9 miles/17.6km

Ascent: 2,122ft/647m

Time: 5-5½hours

Map: Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 Explorer sheet OL16 (Cheviot Hills); Harvey Superwalker 1:40,000 sheet Cheviot Hills

Public Transport: Buses 266, 267, 464, 470, 473, 710 (Traveline 0871 200 2233)

To the west of Wooler, in the far northern part of the county, are the Cheviot Hills – fulsome, rounded and often boggy hills that rise to 815m on the Big Daddy of them all, The Cheviot. Punctuating the northern edge of the range, close to the Scottish border, are some lower tops, often crowned by Iron Age forts. The best known of these, visible for miles around, is Yeavering Bell…

Setting off from Wooler on a warm spring morning, we picked up the route of the St Cuthbert’s Way heading west. Breaking free from the confines of the conifer plantations on Kenterdale Hill and the lumpy hills of Wooler Common, we were quickly striding out under the expansive skies I always associate with this beautiful border county. This is a big landscape, The Cheviot and Hedgehope Hill among the many tops contributing to the majestic scene ahead.

We left St Cuthbert’s Way after about 9km to climb Yeavering Bell, the site of the region’s largest fort. Ascending, we passed through a gap in what looked like an old, tumbledown dry-stone wall. Just moss-covered rocks with bilberry coming up through the gaps between them. Except these weren’t just rocks; they were the remains of the fort’s ancient stone ramparts. More than two millennia ago, they would have formed walls almost three metres high and probably just as thick, enclosing a settlement that was home to members of the Votadini tribe. These Celtic people once dominated the area from the Firth of Forth all the way down to the River Tyne. When the Romans arrived in Britain, the Votadini were at first ruled directly. Then, after Hadrian’s Wall was built and the Romans retreated south, this tribe remained allied with the invaders and formed a ‘friendly’ buffer between the legionaries and the Pictish tribes further north.

Far-reaching views into southern Scotland from St Cuthbert’s Way near Yeavering Bell. © Vivienne Crow

Exploring the summit, 361m above sea level and with far-reaching views over the surrounding landscape, it was just possible to pick out the remains of the platforms where the Votadini homes, timber-built roundhouses, would once have been located.

Throughout the rest of the walk, on our rambling return to Wooler, the landscape threw up more echoes of the distant past. Following a faint trail weaving a secluded route roughly eastward through the northernmost hills of the Northumberland National Park, we passed Glead’s Cleugh, the site of another hill fort, walked through the middle of an ancient settlement on the slopes of Harehope Hill and then skirted the base of Humbleton Hill, home not only to yet another Iron Age fort, but also the site of a 1402 battle between the English and the Scots. Following in the footsteps of ancient peoples, I couldn’t help but ponder the questions modern archaeology keeps throwing up. Why did they pick these sites? Were they really ‘forts’? Some, despite their hilltop locations and ramparts, are barely defensible. Were these people really as warlike as we’ve often believed? What would life have been like on these northern hills 2,500 years ago? And, if we get back to Wooler early enough, which flavour ice-cream should I have at the Doddington Milk Bar?

Keen for more Northumberland walks? Pick up a copy of our May 2018 issue to read Vivienne’s full feature, including three mapped walks.

Header image: Hadrian’s Wall hugs the top of the Great Whin Sill in the southern part of Northumberland National Park. Image © Vivenne Crow