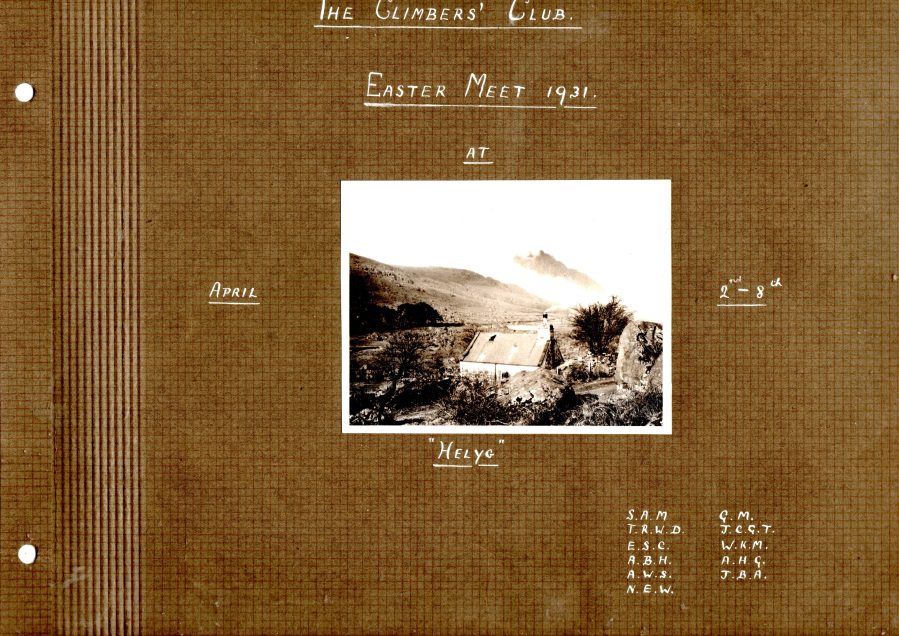

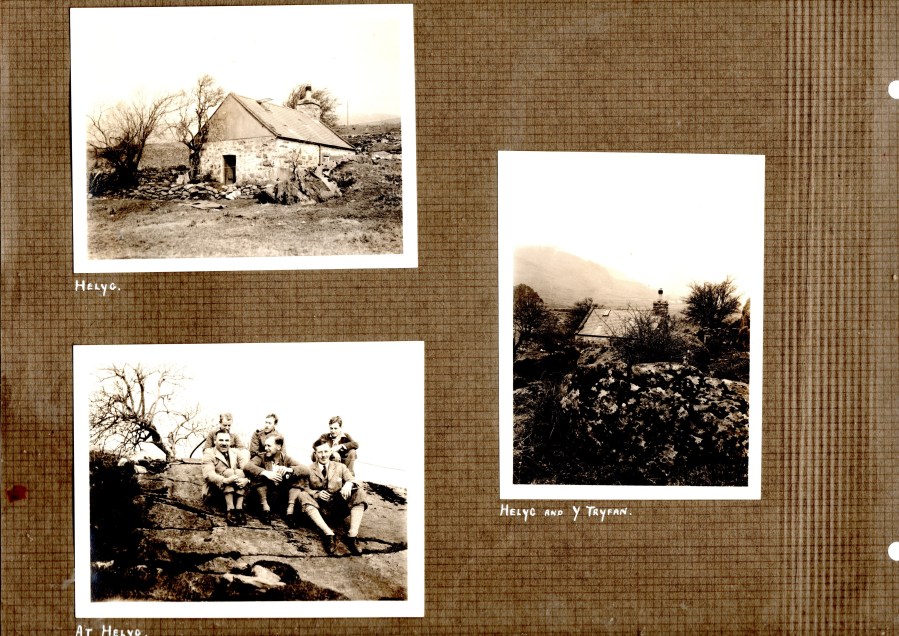

In Eryri/Snowdonia’s wild and weathered Ogwen Valley, between the flanks of Tryfan and the Glyderau, stands a solid stone building that has witnessed a century of British climbing history. This May, Helyg – Britain’s oldest purpose-acquired climbing hut – is 100 years old. Helyg was obtained by the Climbers’ Club in 1925 and has been the launchpad for countless adventures, a shelter from Snowdonia’s storms and a gathering place for generations of climbers.

Main image: Helyg today, Tryfan towering behind | Credit: The Climbers’ Club

Originally a roadmender’s cottage in the 19th century, Helyg was once home to a local man, Mr Jones and – remarkably – his 21 children. Its walls, already weathered by decades of rain and hardship, were reclaimed by a different kind of traveller in 1925 when the Climbers’ Club bought the building for £200.

The club was struggling to revive itself after the devastation of the First World War and needed more than just committee meetings in London. They needed a place in the mountains – a place to meet, to dream and to climb. Helyg became that place. It was simple: stone floors, a smoky fire, mattresses on the ground, water hauled in by hand. Guests paid sixpence a night; visitors, two shillings. It wasn’t much, but it was enough.

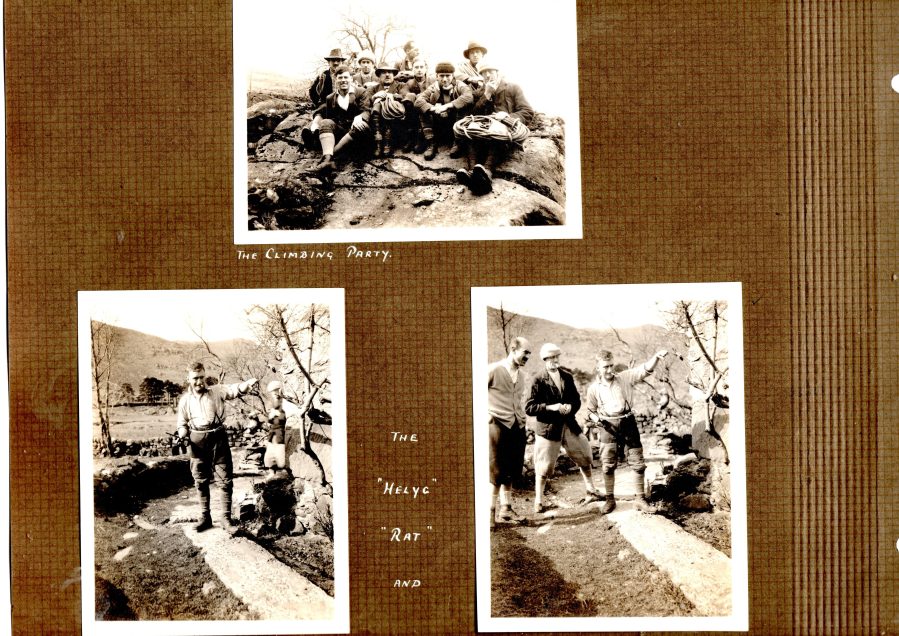

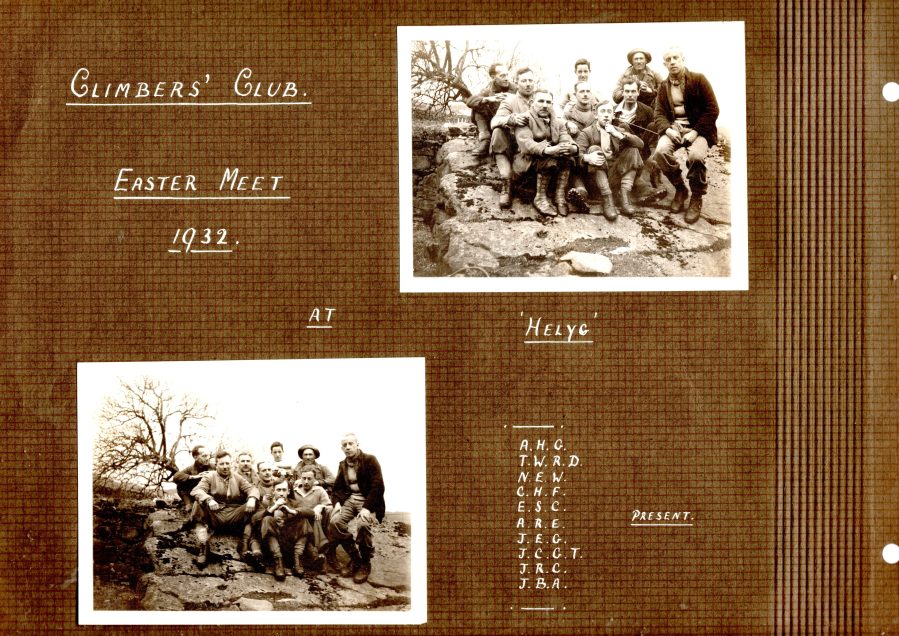

Within a year, 30 to 40 club members had stayed, along with more than 20 guests. From its doorway, generations of climbers set off towards the crags of Tryfan and the Glyderau. Names that would become part of mountaineering legend — Eric Shipton, George Mallory, Bill Tilman — are all linked to these hills and this valley.

Later, during the Second World War, Helyg served a different purpose, used by the military as a “Toughening School” to harden young soldiers against cold, wind, and fatigue before sending them into battle. Its contribution to British climbing history continued through the post-war years, its stone hearths quietly sheltering climbers who would help lead the successful 1953 Everest expedition.

Through all this Helyg remained unpretentious, a little rough around the edges but full of life. The hut became a stage for many smaller, more personal dramas: sodden boots steaming by the fire, long debates over tea-stained maps, climbers scribbling accounts of heroic ascents and minor disasters into the hut’s battered logbooks. Life inside Helyg was never glamorous. But it became, and is, a symbol of the simple pleasures of climbing.

As Helyg’s centenary approaches, plans are underway for a special weekend of celebrations from 2-5 May 2025. There will be talks and a historical exhibition at Plas y Brenin, the launch of a commemorative booklet by long time club member Andy Kitchen, a climbing meet to some of Helyg’s classic crags and an open house for past and present members. Organisers Hilary Lawrenson, Kenny Atherton and Cenydd Lewis have been collecting stories and memories not just to honour Helyg’s past but to remind everyone it’s still a living breathing part of British climbing culture.

Today much of Helyg is the same – though custodianship has its modern challenges. Cenydd Lewis was warden from 2014 to 2017 and remembers a peaceful time: “It was all fine,” he says. “No ghosts, rats or outrageous behaviour to report.” His main worry was water quality and maintenance.

Kenny Atherton, the current warden, says sometimes when he visits he finds lights left on. “I put it down to people being nervous about ghosts or rodents,” he says, half joking.

The biggest modern threat to the hut’s peace and quiet isn’t supernatural. It’s mountain goats. “They eat everything,” Kenny says – including the Helyg Willow, a memorial tree planted by late club member Mike Yates. The goats, descendants of ancient Stone Age herds, have exploded in numbers across North Wales in recent years, especially since the Covid lockdowns.

Helyg’s history has been written into its very walls – it is now a listed building under the protection of CADW. Even its 1931 garage—the oldest purpose-built garage in Wales—has that same status. You can still see the ancient crab apple tree in the garden with its twisted branches, Thought to be hundreds of years old, it has been preserved through grafts taken by the National Trust’s Bodnant Garden.

Over the years, Helyg has seen its share of mishaps: a van driver once tried to make a break for it without a key by dismantling part of the car park wall. But despite that, Helyg stands not as a relic, but as a living link between generations of climbers and their climbing dreams.

Learn more at climbers-club.co.uk/huts/helyg